SPENT MANY YEARS IN SLAVERY

Life Story of Jas. R. Willson of Welland

[People’s Press, 16 January 1912]

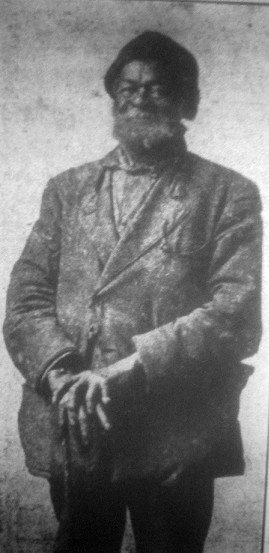

Nearly everyone knows him. Few figures are more familiar on the streets of Welland than his-familiar because to see him is to remember him. This is only one of James R. Willson’s claims to a newspaper writeup. He has many more, as the reader will agree at the conclusion of his story. His photo, which appears above, will be immediately recognized.

Nearly everyone knows him. Few figures are more familiar on the streets of Welland than his-familiar because to see him is to remember him. This is only one of James R. Willson’s claims to a newspaper writeup. He has many more, as the reader will agree at the conclusion of his story. His photo, which appears above, will be immediately recognized.

An old colored man, somewhat stooped by the weight of over eighty years, visage deeply wrinkled, beard more gray than black, but with bright kindly eyes, a happy smile, a remarkable vigor of mind and body, a courteous manner, and a lifelong habit of industry to which he adheres faithfully-this is James Willson as we see him today. It would seem almost an impossible stretch of imagination to connect this genuine picture of secure and tranquil old age with a man hunt in which he was the quarry and there was a price of $200 on him, taken dead or alive. Yet such is the case, for he is an ex-slave from the Southern States and twice ran away from his masters. He was kept in slavery until he was probably between thirty and forty years of age.

He was born in the state of Missouri, his mother being a slave. “When I was ten years old,” he said to the Tribune, “mother was sold away. Oh yes, I remember it. The man took her away in a wagon.” He (James) had two sisters and two brothers, but never saw his father. Later he was sold. The next event he relates is very pathetic. “I never saw mother again for seven years, and then she came down to see her children. That was thirteen years before the civil war and she said I was 17 years old then. I never saw her after that though she lived for many years after the war.” James’ master let him off for a few hours to see his mother, telling him to be home at five. Speaking of the parting he says, “Mother was crying, she was always crying.”

That night he decided to run away and escape to Illinois, which was a free State. He had seen a boat along the river when he was to see his mother, and with a chum stole away about midnight. It was about nine or ten miles to the Missouri river, which they succeeded in crossing. They were now in a free State, in name, but in fact they found the word “free” was a sad delusion, for the whole country was banded together to secure the rewards offered for the return of escaped slaves to their masters in the slave state. The reward was $200 for each one, so that the capture of the two would have been worth $400. Knowing this they kept to the woods, traveling by night. It was Sunday night when they got away and the next night as they were going along men sprang from the bushes and attempted to take them captive. James escaped and later learned that his chum also got away, though he never saw him again. James next encounter was with a good Samaritan who forded him across a river and fed him His luck now deserted him, however, for on Friday he was cornered in a corn field and surrounded by men with guns and clubs. Men were placed on the fences surrounding the field with guns prepared to shoot him if he attempted to bolt, while others searched the corn. He was captured and tied with ropes. The law in Illinois permitted slaves to be returned if captured within 24 hours and in his case, his captors were defying the law but there was no one to interfere, though a jailor refused to have anything to do with him. His captors took him back to their homes and kept him chained to a tree from Saturday until Thursday when he was taken south to Kentucky. After remaining in handcuffs there for six weeks he was sold into slavery again. “The man who got me paid $1026 for me,” he said. “I was sold twice with mother when I was a little fellow, but I don’t know how much I sold for with her.”

His next period deals with the civil war. He had been with his last master for thirteen years and the owner threatened to kill his slaves rather than have them liberated. The Yankee troops were across the river and James made another sensational escape in a boat, his master reaching the bank with a gun as he was crossing. He worked for the Union officers for several months and one bold attempt was made to kidnap him and take him back to his master, at the point of the gun. By a cunning dodge he escaped as his captor was leading him along on horseback. In this case it was a Union soldier who tried to take him back, and the man was severely punished. His experience in the war also includes building Confederate fortifications as a slave, and he was present at two battles, he says.

When the Union army moved on he was advised by the officers by whom he had been employed to make for the North. By stealing rides on boats and freight trains and undergoing great hardships he traveled through Wisconsin and Michigan to Detroit. Here he met a horse dealer and went through to Albany, N.Y., with him, working for a year for him without pay in return for getting him to safety. Then he got a job with a farmer for $12 a month and board, but his troubles were not over. He was destined to again become a fugitve. On this occasion he was drafted to go to the war, which was not yet ended. He had seen enough of fighting, however, and decided to run away again. This he carried out and finally got across the Suspension bridge at Niagara Falls in the night. “They were smart ones who could read and write, but I done them up nicely. Not many educated fellows could make a better dodge than that,” he commented. “I don’t read or write, but as long as I am able I will support myself while I live.”

Shortly after this Mr. Willson came to the vicinity of Welland, then a little burg. He worked on a scow on the Welland river and in the following February was married, the ceremony being performed in the old brick building at the M.C.R. bridge, known as Tuft’s hotel. He is now married for the third time, has had ten children and is a great grandfather, and “I am able to do my day’s work outside yet,” he said laughing.

He lives on Church street with his wife, and a sister spends part of her time with them. He has been working for the corporation for several months and it is often hard and disagreeable. “I have been very healthy this winter,” he said, “but I would like to get a job inside so I wouldn’t be exposed to the weather so much.” He never smoked or chewed tobacco, which will be a surprise to many.

Mr. Willson says his mother died in Texas at the age of 115 years. He hadn’t seen her since the time he ran away first. He tells a laughable story of his visit to his sister in Illinois two years ago when they had not seen each other for fifty years. He also saw the wife of his last master when a slave and she was “as tickled to see him as a brother.”

His memory of scenes, incidents and conversations is wonderful in its detail. “You’d think I had almost forgotten it by this time,” he said with pride, “but I haven’t.”

The tragedy of the slave’s life is scarcely comprehended at the present time but to listen to Mr. Willson’s narrative will compel a certain realization of it at least.

Mr. Willson had made a good citizen and we hope to see him have many years yet of happiness and plenty.

Subscribe..

Subscribe..

Add A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.