Results for ‘General News’

| [May 29, 2025] Introducing “DIARIES and STORIES“: Here you will find the actual content gleened from various diaries, journals, and letters written by Wellanders. |

| [Feb 21, 2023] Introducing “ARCHIVES Search“: Located at the top right portion of the side menu. Select the desired month+year from the dropdown options and the system will list all the posts that were made to the website at that time. NOTE: Main and Events each have their own independent Archives Search function. |

| [Jun 8, 2022] NEW USER LOGINS have been suspended as we investigate a recent hack to the database. The site is currently READ-ONLY mode to UNREGISTERED USERS. Only REGISTERED users may still log in to comment. |

[Welland –Port Colborne Evening Tribune, 24 March 1947]

A report on immigration by Sir Charles Tupper, one of the Fathers of Confederation, was amongst items printed in an edition of the Welland Telegraph, of March 14, 1889, found by Jess Barnhart, Humberstone, in the bottom of an old chest owned by his father, the late Ben Barnhart of Bertie township. The Dominion, said Sir Charles, was not a country for loafers and idlers.

Noted as one of the harbingers of spring was “a superabundance of soft, slimy, sticky liquid mud that sticketh closer than a mortgage.”

One advertisement announced a special meeting of the country council to consider erection of a jailer’s and turnkey’s residence.

A news item told of a Presbyterian congregational meeting to hear a report of a committee to devise ways and means for the erection of a new church. The report was read by the late T.D. Cowper, who was later to become Crown Attorney.

There were advertisements in those days for roadsters, but they didn’t refer to the horseless carriage.

An 1888 edition, reporting a Welland county council meeting showed cost of maintenance for inmates at the Home for the Aged to be $1.85 per week. The report also gave details of the construction of barns and buildings.

Cheese in those days was 12 ½ c a pound and there no shortages of sugar or lard. Merchants invited customers to buy “sugar by the barrel and lard by the tub.”

News was personal, as may be gathered from the following: “A case of domestic infidelity in a local family occasioned some exaggerated rumors this week, but as the parties are again caroled under one roof, vowing eternal constancy, there is no occasion for further gossip.”

[Welland Tribune, 21 February 1947]

Louis Jacques of 66 Patterson avenue brought a copy of the issue of The Welland Tribune and Telegraph, January 9, 1923 to The Tribune office yesterday, It proved to be an interesting document. One note of interest concerned County Judge D.B. Coleman of Whitby, one of Welland’s popular barristers of 10 years ago. There is on the editorial page under signature of “D.B. Coleman” announcing the annual general meeting of Welland Horticultural Society. Judge Coleman was at that time the retiring president.

It was noted in this issue that Mayor James A. Hughes ( Jim Hughes) is still one of Welland’s well known citizens took oath of office, and a mayor of another town. Mayor John Shriner of Thorold wrote the then Federal Minister of Justice a letter of protest against the commutation of sentence of death of Nick Thomas and Harry Rutka to life imprisonment. This news item also noted the reply of Sir Lomer Houin, Minister of Justice to the effect that this particular case was “disposed of on its merits.”

Another interesting item was the construction of the new cold storage plant at the intersection of Hellems avenue and Division street. It was then known as the St. Thomas Packing Company.

Harry Jones was Crowland’s police chief in those days, and the late Magistrate John Goodwin was on the bench.

Louis Blake Duff was the editor of the paper at that time.

Mr. Jacques found this newspaper in the desk at the offices of Macoomb, Macoomb and Street, East Main street, where he was doing a wood finishing job.

[Welland Tribune 1 October 1897]

Ottawa, Sept. 28-The design for a new postage stamp has been approved by the postmaster general. There is a portrait of her Majesty as she appeared at the coronation, except that a coronet is substituted for a crown. The portrait has been engraved from a photo procured during the jubilee ceremonies, upon which was the Queen’s own autograph, so that it is authentic. The corners of the stamp will be decorated with maple leaves, which were pulled from maple leaves on Parliament hill and engraved directly from them. Everything, indeed, is correct and up to date, and the new issue will reflect credit on Mr. Mulock’s good taste. The engraving will take care to make this permanent and ordinary issue a tribute to their skill. The present stock of stamps will take some weeks to exhaust, and not till they are done will the new stamps be issued. It may be about November of this year.

*Sir William Mulock was the postmaster general under Laurier 1882-1905.

[Welland-Port Colborne Evening Tribune, 6 Nov. 1943]

Above is a picture of the members of No. 4 Troop, Welland Boy Scouts, Sacred Heart Parish: -Front Row, left to right-District Commissioner J. P. Megannety, Scoutmaster Philippe Audet, J. Laland, A.Lemelin, L. Corriveau, L. Demers, R. Larouche, A. Costllo, also Assistant Scoutmaster Arthur Loranger.

Second Row-Cubmaster Antonio Pellerin, L. Marois, L.Cunningham, R. Beaulieu, P. Lamarre, Y. Lamontagne,

Third Row-L. Hardy, P.L.; R. Demers, S.P.; R. Nantel, P.L.; R. Gerard, H. Beaulieu, P.L.; R. Demers, S.P.; R. Demers, P.L.

Fourth Row-R. St. Louis, R. Costello, R. Poulin, , M. Gibbons, L. Beauparlant, J. Labbe, L. Baiano.

Last Row-R. St. Louis; Assistant Scoutmaster Napoleon Jolin, Troop Leader Robert Nantel, Senior Patrol Henri Demers, Roger Latulippe and L. Picard.

By Lara Blazetich

Welland Tribune

Compiled from the files of the writer’s grandfather, George “Udy” Blazetich

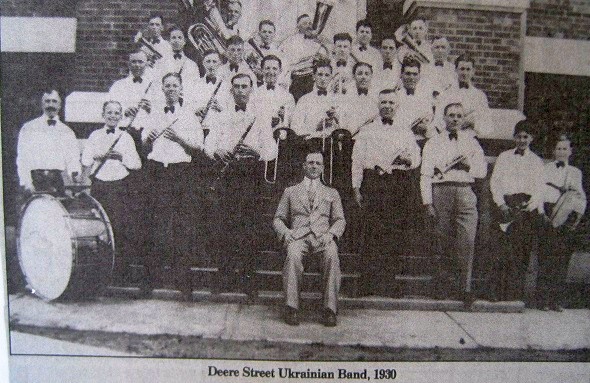

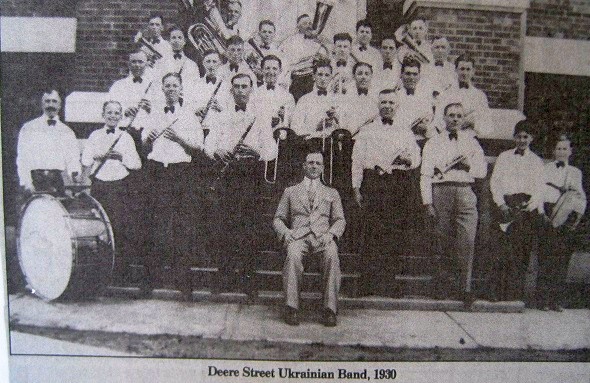

The Deere Street Ukrainian Band of Crowland was a popular feature at various functions in and about 1930.

The members of the band in this contemporary photograph include, seated in front: bandmaster Mr. Zikiewicz and standing in the front row, from left, George Repaski, drum; Joe Kisway, Nick Kisway, Adam Loziczki, Tony Mabalias and Julian Skorenki. The names of the last two people in the row are unknown.

In the second row are Frank federovich, Joe Kazmir, Sam Pankkiw, Julian Greshchuk, John Krywan and Harry Humeny.

The third row has Peter Guzda, Walter O’Bireck, Joe Pededworny, Peter Uberna and Peter Huczuliak.

Standing in the back row are: (unknown), John Roschuk, Archie Shutic, Mike Lorizki, Sidor Crouch and John Smalyga.

*The photo was taken by Katie Crouch and the names were compiled by Walter O’Bireck.

By Guardian Writer

TIM BYNG

Date Unknown

Ontario Heritage Act-8 November 1986

One of Welland’s most historic buildings has been approved by Welland city council for heritage designation.

The Fortner House, now known as Rinderlin’s Dining Rooms, at 24 Burgar St., has been recommended for heritage designation by the city’s Local Architectural Conservation Advisory Committee (LACAC).

Betty Ann DiMartle, LACAC chairman, told city council last week the property was considered for designation through research carried out in the summer of 1984 with the assistance of students employed under a Canada Summer Works grant.

The research indicates that the property and structure is deemed to have sufficient architectural and historical significance to the city to be designated as a heritage property.

City council approved the processing of the structure for heritage designation under the Ontario Heritage Act.

DiMartle outlined the history of the structure to city council.

PURCHASED 1835

In 1835 the lands, which are adjacent to what is now the corner of East Main and Burgar Streets, was purchased by Thomas Burgar, the first postmaster for the Village of Welland.

Burgar Street, in all likelihood, was named after the Burgar family.

Burgar had a plan registered in 1855, dividing a portion of his holdings for sub-division purposes.

The lots were sold to George H. Burgar, the son of Thomas Burgar, in 1859. Based on available records, it is believed the house was erected on this property in 1859.

George Burgar was a carpenter by trade and was very active in local politics. He was an alderman for 19 years between 1871 and 1912. As well, he was mayor of the Town of Welland and in 1893 and 1894. In 1874, he succeeded his father as postmaster.

In 1868, Burgar sold the house and property to Jonathan S. Chipman. In the same year, Dr. W.E. Burgar, son of George R.E. Burgar, began his medical practice out of the house.

Several land transactions took place over the next several years. In 1875, John McDonald and others, sold the property to Mary L Burgar, the wife of Dr. W.E. Burgar.

During that period or ownership, in 1884, a large addition was made to the original house.

In 1888, a prominent citizen, Dr. Sinclair H. Glasgow, married Nancy Fortner, who had two daughters, by a previous marriage, Gertrude Maude and Theo. The following year, Nancy C. Glasgow purchased the property.

Dr. Glasgow was an alderman for the Town of Welland in 1891 and mayor in 1895 and 1896, and was the medical officer of health for Crowland.

In 1922, the property, which was to become known as the Fortner house, came under the ownership of the two Fortner sisters. The last sister, Gertrude Maude, died in 1970 and the original furnishings were auctioned off and the property put up for sale.** The last sister to pass was Theo Graham Fortner: 1881-1970. Gertrude Maude: 1879-1968.

RINDERLINS

During the next decade, there were several owners, and uses made of the property. In 1980, Emil Rinderlin purchased the property, renovated the house, and in 1981, opened up Rinderlin’s Dining Rooms.

“Mr. Rinderlin has undertaken extensive renovations to ensure that as much of the original structure as possible has been maintained,” the report said.

The three storey frame structure is an excellent example of the Queen Anne Revival Style probably the result of the major addition constructed in 1884.

This style was a result of a design period which “revolted at the rigid rules of classical architecture,” according to the LACAC. Report. The house is characteristic of the Queen Anne Revival Style by its “asymmetrical composition and whimsical detail which is evident in its turret, window gables, dormers, porches and balconies.”

This period also exploited fine materials in a “creative off-beat manner.” This is obvious in the original finishes of fine wood, unusual mouldings, panels and a handsome stairway.

Other significant adornments include a spindle tracery offset over the fireplace, a curved glass window and mirror at the front entrance, which at one time allowed a clear southern view down Burgar Street. The unusual half circle motif of the stair balustrades, which appear to be a fine cherry or mahogany, “would be typical of this period,” the report stated.

[Welland Tribune, August 1983]

It’s been 65 years, August 6, 1918 to be exact, since the steel scow or barge lodged in the Niagara River, about ¼ mile above the Horseshoe Falls. The scow to this day remains a mute reminder of near tragedy and a spectacular rescue. Briefly here’s the story.

That steel barge, loaded with rock and with three men aboard, was being towed to the upper river by a Hydro tug, when its tow line boke and set it adrift. One of the men plunged into the river at once, and swam shore. Soon the River’s swift current seized it and carried the clumsy steel craft quickly toward the brink of the Falls. However, the men on board had the presence of mind to open the dumping hatches in the bottom of the craft and thus admitted enough water to go aground.

Frantic efforts were begun to rescue the two stranded me. All that night and until late the next afternoon, attempts were made to devise some means of getting the two men to safety. The only hope was to shoot a line from the roof of the nearby powerhouse and rig a breeches-buoy onto it. After several lines had fallen short, the men were finally able to grasp one and make it fast but before the buoy could be rigged, the lines became tangled, preventing the buoy from reaching the barge.

Red Hill Sr., a famous Niagara River daredevil, volunteered to swing himself out to the obstruction, hand –over- hand above the ragging water. A false move, a broken rope or a sudden lurch of the Scow would have carried him to sudden death. There he clung by his legs while he straightened the lines with a Marlin spike. The breeches-buoy finally reached the scow and the men aboard were rescued.

Buffalo Courier’s Report

[Welland Tribune, 13 July 1900]

Niagara Falls, N.Y., July 9-In his boat the Foolkiller, this afternoon, Bowser of Chicago, has navigated the terrible whirlpool rapids of the Niagara River in safely and is now one of the curiosities of the country. The much advertised affair occurred this afternoon.

The boat was launched last night on the Canadian side of the river near the Maid of the Mist landing, and this morning it was towed to the American side, as Bowser had promised the Canadian police that he would not board the boat from that side of the river, providing they let him put it in the water.

Bowser secured a boatman to tow the boat down the river just below the milling district where it was moored to the bank. Here at 3 o’clock he went and for an hour was busy preparing for his remarkable voyage.

The river banks for miles down were lined with a curious and skeptical crowd. His boatman started to tow the boat out into the river at just 4.30 o’clock.

The craft started all right and began to drift down. It shot the “swift drift” at ten minutes after four, and passed over towards the American side. Here it reached a current that swept the boat over to the Canadian shore and in a few moments it was caught in a powerful eddy made by one of the little bays of the river on the Canadian side and was whirled around in it three times, taking over half an hour. Bower signalled to his boatman who was on the bank, and he came and towed him from the eddy. This was at 4.50 o’clock. The Foolkiller then started direct downstream in the middle and came down towards the Cantilever bridge of the Michigan Railroad with the swift current. It escaped all the eddies and shot under the railway steel arch bridge into the terrible whirlpool rapids at exactly 5 o’clock.

The Foolkiller behaved handsomely and rode the first waves capitally. Bowser waved his hat carelessly to the crowd above him and smiled reassuringly. The second heavy wave swept completely over the boat, submerging Bowser. On and on the mad rush of water swept the Foolkiller, but always keel down and Bowser in the cockpit, all right.

When near the centre of this fearful piece of rapids the boat was turned broadside and took several big seas, but did not capsize. The monstrous waves finally turned her bow on and swept over it. For several seconds at a time, the boat with its occupant, was out of sight in the raging flood, but again it would appear, always right side up, with Bowser half drowned, but still in that boat.

Bowser was alive, but he did not have any time or heart to wave his hat. He was grittily hanging on for his life in the little cockpit of the boat. In less than five minutes he had run the rapids and had shot into the great whirlpool. After having one or two pretty fierce shakings in the fierce swirls of this pool he was carried around into the smoother water and whirled about.

Bowser and his boat were in the whirlpool from 5.05to 5.40 o’clock, moving around at the will of turbulent water. Twice the boat entered the centre of the pool and was submerged. Bowser had no control over it. Finally the craft struck a current that took it to a point about fifty yards from the shore, and Arch Donald, Frank Hyde and Howard Lake swam out and towed it ashore. As the navigator stepped out of the boat he exclaimed, “What is the matter with Bowser now?” A fire had been built and the navigator was given a change of clothing. He was shivering as with the ague. A hundred or more people who had descended the wild and torturous Indian path shook his hands and congratulated him.

To a Courier reporter he said, “It was an awful experience. The whirlpool rapids are nothing like I had thought they were. They are many times rougher. Had I known the truth I never would have attempted the trip. I have no idea of trying again. I have got the laugh on those people who wanted to introduce me to the coroner, but the people have got the laugh on me in the matter of the boat line for the Pan-American. I have been through the rapids safely, and if that is encouragement enough for anyone to start a pleasure boat line, why they are perfectly welcome.

“After I passed through the first big waves that engulfed me I found that my hat, which had been drawn tightly over my head, had been washed off. I waved it off, and then some waves struck me, and it was all off. I didn’t realize much of anything after that until I came out into the whirlpool. During the brief time that I was going through the rapids it seemed as if a hundred men were pounding my head and the boat with great hammers. The boat never turned over, but it was on its side and ends several times. Each time I thought I was a goner sure. Only the straps, which at the last minute I decided to fasten to the boat and over my shoulders, saved me from death. I did not say any prayer; I did not have time to think of one. I was mighty cold and tired when I came out into the whirlpool. I will rest now until next Saturday, when I must be back in my work in Chicago, as my two weeks’ vacation ends then.

“I haven’t done this to get dime museum fame. I honestly believed that a boat line through the rapids would be practical, but I am convinced that it would not be. I would not make another such trip for any amount of money. I got through by rare good luck. I would forget it if I could. Three or four times my breath was nearly gone, and then the waters would open and let in some air. I did not use my steering apparatus at all, for I couldn’t. I just went into the rapids and the rapids did the rest.”

The navigator was taken to his hotel in a carriage. The boat is still in the whirlpool. A number of ladies shook hands with Bowser after he landed. The first was Mrs. Harry Castle of Detroit, and the second Miss Alma Garrett, of Niagara Falls, Ont.

Bowser is an assumed name for this daring navigator. His real name is Peter Nissen. He is a Dane and is 37 years of age. He was born in Denmark and came to this country seventeen years ago with his parents and settled near Chicago. For several years past he conducted a private school on the west side, but teaching not being profitable, he left it to make bookkeeping his business.

He was fifteen months building this boat, and did a great deal of the work on it himself. The immense weight of the keel, which was a steel shaft, hanging below the wooden keel, was the real success of the boat. There were four large bulkheads and six air-tight compartments, filled with cork. It was very strongly built and was able to withstand the terrible pressure and strain put upon it without a scratch or the breaking of a timber. The boat weighed 4,300 pounds and the keel nearly a ton. Bowser had given great study to the river and the rapids. He visited here in the spring and secured a walking pass on the Gorge Road, which skirts the water’s edge, and watched the effect of the big ice floes going through the rapids and the currents of the river. He made up his mind then that he could successfully navigate the rapids and went back to Chicago fully determined to build a boat that would carry him through.

Wonder if the Twentieth will keep up with the Nineteenth

[Welland Tribune, 15 September 1905]

-

The nineteenth century received the horse and bequeathed the automobile.

-

It received the dirt road and bequeathed the railroad.

-

It received the sail boat and bequeathed the ocean liner.

-

It received the fireplace and bequeathed the steam and gas range.

-

It received the staircase and bequeathed the elevator and escalator.

-

It received the hand printing press and bequeathed the Hoe cylinder.

-

It received hand-set type and bequeathed the linotype.

-

It received the goosequill and bequeathed the typewriter.

-

It received the painter’s brush and bequeathed lithography, the camera and color photography.

-

It received ordinary light and bequeathed the Roentgen ray.

-

It received gun-powder and bequeathed nitro-glycerine.

-

It received the flintlock and bequeathed the automatic Maxim.

-

It received the tallow dip and bequeathed the arc light.

-

It received the beacon light signal and bequeathed the telephone and wireless telepathy.

-

It received wood and stone buildings and bequeathed twenty-storey steel structures.

-

It received letters sent by a personal messenger and bequeathed a world’s postal union.

-

It received the medieval city, a collection of buildings huddled within walls for safety and bequeathed the modern city, lighted, paved, sewered and provided with five-cent transportation.

-

It received a world without free public schools and left no civilized country without them.

-

It received a world in which men voted only in America, and left them voting in every civilized country.

-

It received a world without a voting woman, and left it with some measure of woman suffrage in nearly every civilized country and full suffrage in a large section of the earth’s surface.

-

Is the twentieth century going in for breaking after this style? If so, it will have to hustle.

-

But, really at times it seems as if the twentieth century would usefully employ itself in just utilizing the discoveries of the nineteenth.

-

Steam heat, gas ranges, elevators, bath tubs and other nice things are in the world. Why not make them available for everybody?

-

Then there is the land. That has always been in the world. Why not make that available for everybody?

-

The nineteenth century discovered the kindergarten.

-

The twentieth could usefully make it available for all children.

-

It discovered the Roentgen ray, but lots of people can’t afford to pay for just plain, ordinary sunlight in their houses.

-

The inventors are a very wonderful class of gentlemen-women, too, now-a-days-but it really seems as if the twentieth century didn’t need them so much as some plain, practical people to utilize what they’d done already.

-

And then, again, it sometimes seems as if the little, young twentieth century had all it could do to manage the problems which the nineteenth bequeathed along with its blessings.

-

The nineteenth century discovered how to make people live in perpendicular layers instead of beside each other on the ground, as they used to, and bequeathed the problem of congested population.

-

It discovered the ocean liner and bequeathed the steerage.

-

It took the weaving out of the hands of women and sent her to the factory.

-

It discovered how to make things by steam, and bequeathed trusts, unions, strikes, lockouts and child labor.

-

It did away with the slave and the serf and bequeathed the proletarian.

-

It discovered the automatic Maxim and bequeathed imperialism.

-

The nineteenth century yelped gleefully over the attainment of political rights.

-

The twentieth century sees wearily that political rights are only a step on the road to economic rights.

Subscribe..

Subscribe..