When the farmer woke up he saw it was a sunny day

So after breakfast he went out to bale some hay

The wheat was ready to be cut down

Then with the tractor later in the field he as found

The cows waited each night for milking time

As they knew he’d be in away before nine

The oil truck came and filled up the tank

But after seeing the bill he didn’t say thanks

His wife had supper ready when he sat down to eat

Feeling this farming life is sure getting me beat

All the children have left for jobs far away

So for help he had to hire and them also pay

The farmer’s job isn’t easy with the pay real good

And working long days he’d never leave if he could

The tractor has a problem that he must solve and get going

As snow is coming soon that he is knowing

After milking in the morning the cows are put out

Then in the evening he hopes again for the same amount

When done with the crops he cuts some logs

And sends animals to market in the fall including hogs

If he was sick the neighbours done the chores

But now a days I feel its one thing that’s no more

What he buys is expensive there’s a mortgage over his head

He feels that paying out money he’ll never get ahead

At night he crawls into bed and sleeps like he is dead

While troubles and concerns pass through his head

There is no thanks for him there under the hot sun

But I thank him each day for the work he has done

He can’t go far with cows to milk each day

And if someone is hired to them he’d have to pay

If it wasn’t for the farmer what would we all do

There’s less of them each day trouble is coming for me and you

Winston E. Ralph

Bancroft, Ontario

The old school house sat on the prairie so wide

And we’ll never know how many tales it does hide

As most pupils are gone that went there years ago

Some older ones may be alive since others may know

They walked from home a mile or two around

And since they were tired they just sat down

In the winter they built the fire so the school was nice

When the teacher and other pupils came not a room of ice

Their lunch pail was one that had jam in it before

And the boys had bare feet in the summer coming in the door

They didn’t need a gym as they got their exercise coming to school

So the teacher taught large classes as they didn’t act the fool

In the morning before they came there were chores to do

At night returning from school they also found a few

They cleaned the pig pen and gave the cows some hay

And the garden was weeded also no time to play

Eggs had to be gathered and the chickens were fed

Their days were filled with chores until time for bed

They stayed at home in the spring and helped plant crops

And the fall was the same until the harvest did stop

In the summer they were in the hayfield forking hay

As everything was done manually back in the olden days

There was also wood to be cut and put in a pile

While the feast of each meal sure made them smile

Sap was boiled down in a pan each and every spring

As this was the sweetener they used on all things

Others skidded logs in the bush at a young age

And when told to do it they didn’t go into a rage

The garden was harvested in the fall and things put away

Since little food was bought they had food for cold days

Saturday night they were free and took the buggy to town

To see friends have a dance or just look around

They had little education but designed many things

Which made them feel like some earthly King

Winston E. Ralph

Bancroft

Small villages are disappearing there’s nothing much anymore

Not like back in the olden days of yore

The schools went from early Sept until late June

But must have closed now yes much too soon

The children are bused to a bigger school farther away

Even though a higher price for fuel we all pay

Fuel is high priced but at the school there’s many cars

Youngsters drive now even though they don’t come far

The stores are closed also as folks shop elsewhere

Instead of keeping the local going as its right there

The church is closed too and left there alone

Where there’s a yearly service when folks come home

Years ago men met at night there in the store

Where they talked and complained like never before

When someone wished to talk they got on the phone

Which they could do in the privacy of their home

The general store ordered things which usually took awhile

But when it came in on your face was a smile

If the men weren’t in the village on the farm they were found

Unlike today they weren’t travelling the world around

The school buses went each day regardless of the weather

As they had a full load and no one was tethered

Work wasn’t somewhere else it was there on the farm

Like planting crops fixing fences or building a barn

You may not agree but they were the good old days

Since we always done things only the right way

Unlike today you went to bed with an unlocked door

Today if you do it you invite trouble for sure

Yes today crime is encouraged unlike yesteryear

And as long as we do as we do it will continue I fear

Winston E. Ralph

Bancroft

Don Messer was a quiet man hardly saying a word

But when he played the fiddle great tunes were heard

He was born in New Brunswick back in nineteen 0 nine

And no one knew he would help them forget hard times

His brother said keep Donald from my fiddle when I’m away

Then at 5 years old Donald found it and started to play

When his brother went west he took the fiddle too

Leaving Donald to wonder now what can I do

Later he got his own which cost $1 and ninety-eight

As it wasn’t his brothers but his own he really felt great

At age 7 before a crowd he felt he was in clover

He knew just one song playing it over and over

His second one was better so he played the neighbourhood

After working the wheat harvest he knew playing was good

He knew a living he could make as folks he did entertain

While his grandpa and others didn’t feel the same

After going to Boston for lessons he returned back home

To form his own band and never again play alone

Charlie Chamberlain went to Saint John to see his wife

Then joined Dons band for the rest of his life

Don wanted to be known locally so he didn’t go far

So he stayed close to home where he went by car

He married and moved everyone to Prince Edward Island

Where life got much better keeping Don smiling

At the first Don was away a lot wishing to be back

Then tried to be home more after his first heart attack

Don Messer and His Islanders they were called after 30 nine

Later he moved to Halifax until the end of the line

The C.B.C. said in 69 it’s time to cancel the show

Even though folks liked it and still would I know

Charlie always sang good either sober or after a drink

While the C.B.C. isn’t like it was thats what I think

I still recall Charlie doing a little stepdance

Yes a reason people tuned in when they had a chance

What I’d give to see Don play and Charlie dance once more

And see the Buchta Dancers as they twirl around the floor

If you don’t remember it or at the show didn’t look

Just read the story by Johanna Bertin its sure a good book.

Winston E. Ralph

Bancroft

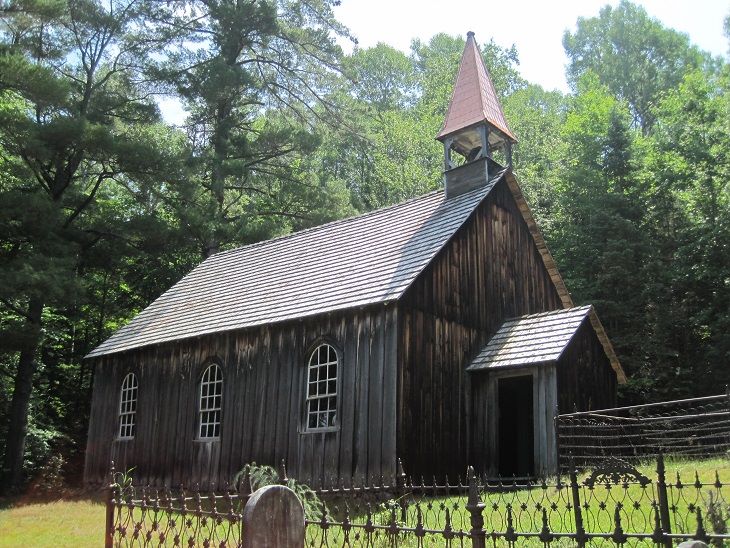

High on the hill of that old Rockingham town

St Leonards Anglican church there can be found

It was built in 1875 yes back a few years

And to see its condition fills my eyes with tears

A post and beam construction with board and batten siding

As the siding is wood how much rot is it hiding

John Watson came to Canada as he married the family maid

The fee he put to good use as to stay away he was paid

He brought skilled folks with him to build the hamlet

It had a store, school, saw mill etc. and a church you bet

As the town declined with the local lumber trade

The church fell into disuse up there in the shade

The pews font and bell were taken to churches including Killaloe

Why would anyone a thing like that they would do

The last regular service was held in twenty-four

And did the folks wonder if there would be anymore

The roof was reshingled and the back wall they did repair

Then the pews were to go back in the seventies there

John deeded it to the Anglicans in Ottawa before his death

As he knew that shortly he would take his final breath

In 1882 they added a porch communion rail and organ

A stove and belfry and bell followed to make it hum

It was empty before and was the second time again

So did the local folks while looking feel any pain

In May of 67 Bishop Reed of Ottawa done the secularation

Then it became just an old building in our nation

In 1995 a group was formed to undertake its repair

So that for a few more years on the hill it will be there

The crowd was happy for couples when their hearts were entwined

There in that little church up there under the pines

Other times it was sadness they felt when they said goodbye

After carrying someone up the hill without a dry eye

In 2022 there was to be an annual anniversary celebration

To lift the locals spirits and others across our nation

It should be moved to a level spot near the old store

So that older folks wanting to go there won’t have a chore

Winston E. Ralph

Bancroft, Ontario

MORE images of the church: [1] … [2] … [3]

By Robert J. Foley

[Welland Tribune, Date Unknown]

William Hamilton Merritt stood on the floor of his grist mill and watched the feverish activity as they attempted to get as much done as possible before the mill shut down. The level of the Twelve Mile Creek had been dropping steadily in the last week and soon the great water wheel would be high and dry. The shutdown could last for weeks or even months with the loss in business and the financial pressures that accompanied it.

To add to the pressure a monetary crisis was brewing in England that had begun to affect the business in the colony. Merritt had gone up to Montreal and had received a very low price for his goods because of the shortage of cash. Things looked gloomy for business prospects for the balance of 1818.

On his return from Montreal he found all the mills idle and a backlog of timber and grain to be processed. Merritt then resolved to pursue an idea that had been lodged in the back of his mind since his days of patrolling the upper Niagara River during the war. If he could dig a ditch from the Welland River to the head of the Twelve Mile Creek his water problems would be over. To pay for the project he envisioned a canal that also would carry boats to bypass the Falls of Niagara.

Taking the imitative, he went about the district gathering support for his proposal. The idea of a canal was not as revolutionary as we might think. This was the age of the canal. In Britain the young Duke of Bridgewater had toured the Canal du Midi in the Languedoc region of France in 1753. He was so impressed that he began to build his own canals in England using the French model. The Canal du Midi had been in operation since 1681. In the United States, two small canals had been built in the 1790s. The Santee Canal in South Carolina, 22 miles long with twelve locks was completed in 1822 with the Champlain Canal linking Lake Champlain with the Hudson opening the following year.

In the summer of 1818 Merritt, with his friends, George Keefer, a merchant and mill owner from Thorold and John Decew also from Thorold set out to make a rough survey of a possible route. With a borrowed water level belonging to a mill owner at the Short Hills the three set out. Starting from the south branch of the Twelve Mile Creek at present day Allanburg they proceeded due south to the Welland River a distance of two miles. They reckoned the dividing ridge to be 30 feet above the level of the creek. It was later proven that an error of 30 feet had occurred and the height was actually 60 feet. Merritt and his partners were not the only ones thinking canal in the peninsula. The inhabitants of Humberstone and Willoughby Townships advocated a canal from Lake Erie to the head of Lyons Creek. Bertie Township pushed for a canal to avoid the rapids at Fort Erie. John Garner of Stamford remarked that, “Locks may be made to pass the great falls and connect Lakes Erie and Ontario; but many years must elapse before the province is rich enough to afford the expense.”

The British government was also interested in a canal. The vulnerability of shipping should another war erupt with the United States was of great concern. Ships would have run the gauntlet of guns all the way to Queenston when coming from Lake Ontario and from Fort Erie to Chippawa on the other end.

The government was also planning to survey a route from Ottawa to Lake Ontario. The rapids at Lachine were being eyed as well. However, talking was one thing, building was another.

While others dreamed and talked, Merritt plans in hand, went into action. He approached the legislature for an appropriation of funds for a proper survey of his route. Sir Peregrine Maitland, the Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, having built a summer home at Stamford, was most interested in the project and lent his support to the scheme. The legislature set aside $2,000 for the purpose and hired an engineer by the name of James Chewett to do the job.

To Merritt’s dismay, Chewett scraped his proposal and embarked on a much grander canal scheme that was doomed to failure before it began. Chewett began his survey at the Grand River passing just west of Canborough into Caistor where it was to swing east into Gainsborough. It then swung north crossing the Twenty Mile Creek and descending the escarpment between Beamsville and Vineland. The canal turned west from there and following the escarpment, ended at Burlington Bay, a total distance of over 50 miles.

Although Merritt’s main motivation for a canal was one of water rather than shipping a new impetus for construction of a ship canal in the form of the Erie Canal. The Erie Canal began construction in 1817 to link Lake Erie with the Hudson River allowing goods from the upper lakes to move directly to New York City. The bulk of trade thus would bypass Montreal and Quebec leaving Canada a backwater in the scheme of continental business.

With the rejection of his proposal by Chewett, Merritt’s financial situation became critical and dark days lay ahead for him both financially and personally.

[Welland Tribune, Early No Date]

Visit the Welland Museum in the old Carnegie Library

140 King Street

Welland, Ontario

The Welland Museum, housed in a completely renovated schoolhouse, records the history of the city since the first settlers arrived.

The earliest inhabitants of the region were the neutral Indians, whose way of life is described in the museum. The Neutrals tried hard to avoid conflicts with other tribes but were eventually wiped out by the Iroquois.

Exhibits include pictures of one of their villages and maps showing where they were located. Chipping flints, scrapers and a stone knife found in excavations are displayed.

A corner of the museum where the story of the United Empire Loyalists is told displays an old spinning wheel, snowshoes, a cradle and a sideboard.

The first wave of Loyalists arrived in Canada because they were no longer welcome in the United States but was followed by a second wave composed mainly of settlers seeking inexpensive land. Records show that only about half had English backgrounds. Many had Dutch, German, French and other ancestries.

The building of the first Welland Canal brought a third major group of people to the region because, with the primitive construction equipment then used, many hands were needed to dig the canal.

The majority of the third group were Irish who had originally emigrated to the U.S. to help construct the Erie Canal. When it was completed they moved to Canada to build the Welland Canal.

The most interesting exhibits in the museum relate to the building of each of the four Welland Canals. Models show the section of the canal which passed through Welland as it has appeared at various times.

One showing it as it was when it was first opened includes a reproduction of an aqueduct constructed of white pine that carried the canal over the Welland River, leaving sufficient clearance beneath to allow the passage of boats using the river.

The model of the second canal shows it as it was when it was completed in 1845. A new aqueduct had been built of stone and a wooden swing bridge could be moved out of position by hand to allow boats to pass had been installed.

A third canal is seen as it appeared in 1915, with a new swing bridge called the Alexandria Bridge. It was opened to traffic in 1902 and was operated by steam.

A model showing the fourth canal indicated its appearance in 1935 after a syphon culvert had been constructed to replace the aqueduct. Six concrete pipes carried the river underneath the canal.

In 1973 the Welland Canal Bypass was opened and diagrams show how a 4-tube syphon culvert now carries the Welland River under the Canal Bypass.

Welland in Victorian times is represented in the museum by a furnished parlor typical of that era, complete with framed lithograph of Queen Victoria, an organ, a phonograph with cylindrical records, a showcase with typical crockery and glassware, a harp, a stereopticon and antique dolls. Press a button and you can listen to recordings made in that era.

Children visiting the museum enjoy the Whirligig. It is contraption of wooden toys built in 1978 by G. H. McWhirter, age 84 years. The little operating figures are all driven by a single electric motor.

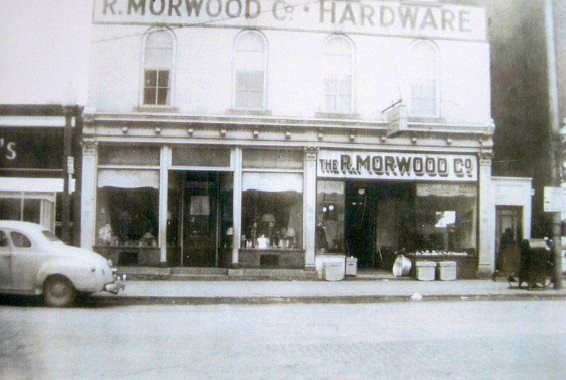

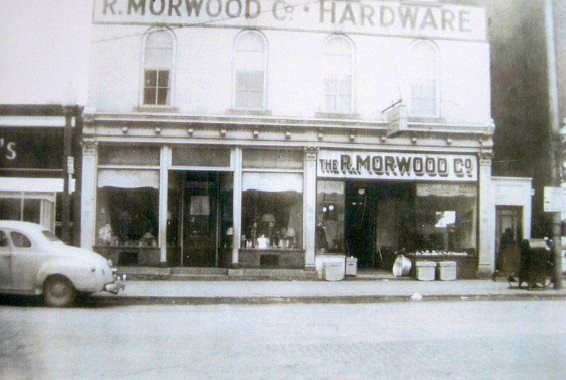

At the rear of the museum there is a blacksmith’s shop and a general store with showcases made in 1890, now used to display artifacts dating from the last century.

By Gerald D. Kirk

[Toronto Paper, Date Unknown]

Mr. Kirk was the 2nd prize winner.

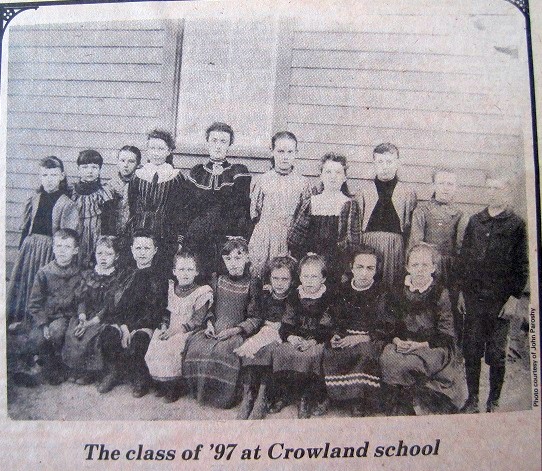

It wasn’t a village, much less a town, just a random collection of crude dwellings and outbuildings along two main trails that intersected at Calvin Cook’s mills. Lyon’s Creek, that gave power to the saw and grist mills, was swollen from the uncommonly heavy autumn rains that had made a morass of much of Crowland township. Now in mid-October wheat from surrounding farms was still in the process of being ground into flour and meal, some earmarked for the British forces camped at Chippawa.

Calvin had been hard-pressed to accommodate the multitude of farmers anxious to transform their grain into flour before the onset of winter. Two years of war had devastated much of the Niagara frontier, and most other mills south of the Welland River lay in ruins.

But as they worked, the millers cast anxious glances out of flour-dusted windows toward the road from Fort Erie, with that special anxiety civilians feel in the proximity of two frustrated and desperate armies. For days the settlement had lived in a constant state of alert, an alert sharpened by the sight of Brown Bess muskets issued to the farm boys guarding the mills.

It was less than an hour after daybreak. The grey smoke of cooking fires mixed with mist still rising from the Niagara and from the campground sprawled low and soggy on its west bank. Fewer men had turned out for reveille than the day before, and the grim shadow of dysentery now hung over the tent of commander, U.S. General George Izard. A large column of infantry and cavalry that had been formed up on the river road began crossing the log bridge over Black Creek, wheeling left onto the trail leading away from the river. Ahead lay the dismal tamarack swamp that Niagara folk did their best to avoid at the driest of seasons.

The horse soldiers led the way, and behind them the commandant of the expedition, Brigadier General Daniel Bissell. His orders were safely tucked into a pouch in his saddlebag, but the contents kept coming to mind: “proceed to Cook’s Mills…reconnoitre the area….destroy the grain and flour…await reinforcements.” Not mentioned on paper but an objective nonetheless was the capture of Misener’s Bridge and the bridge at Pelham/Thorold line, both strategic crossings over the Welland River. Both were in easy marching distance of Cook’s Mills. But what if something went wrong. The prospect of a retreat back across the tamarack swamp caused beads of perspiration to appear on Bissell’s forehead despite the coolness of the October morning.

The sun was already past its highest point in the sky when the American column finally reached the deeply rutted road to Cook’s Mills. Tired and hungry, the men squatted along the road on whatever dry object they had or could find, and munched the hard biscuits each carried in his knapsack. The pause was mercilessly brief, and soon the march was resumed. Less than two hours later the dragoons in the vanguard spotted smoke from the cabin chimneys of Yokum, Buchner and Cook.

Shots were fired by the militiamen guarding the causeway over Lyon’s Creek, but the small force of defenders scattered as the Yankee dragoons charged, sabres gleaming in the afternoon sun. The last to attempt to escape, militia Captain Henry Buchner was quickly surrounded by dragoons and forced to surrender. Women, children and the elderly peeked from their places of concealment to behold the astonishing sight of a seemingly infinite number of blue and grey uniforms flooding their settlement.

Orders were immediately issued to set up camp, and the soldiers began assembling the small tents that would shelter them for the next two nights. By dusk the fields opposite the mills were a sea of canvas, and the men were beginning to build fires to cook their evening meal of dried peas thickened with crumbled biscuits.

Suddenly, there was a commotion on the outskirts of the encampment as plucky farmwives belabored some soldiers for pulling down fence rails to use for fuel. To no avail; before long, most fences in the vicinity were only a memory.

Sleep would come hard for most of the American soldiers camped on the damp ground that chilly October night. Many were natives of southern States and not at all accustomed to the Niagara autumn. But their discomfort would be forgotten as the report of musket fire echoed form the direction of the outpost east of the mills.

The disturbance lasted on a few seconds, but it seemed like hours to the men crouching near the fires, gripping their muskets. Then the only sound was the whisper passing from group to group…”He was one of ours” Then an uneasy stillness returned.

Hardly had the stars and stripes been hoisted up the makeshift flagpole the next morning than green uniforms were spotted on the Chippawa road. Glengarries! Lightly equipped with short flintlocks designed for guerilla-style warfare, these hardy soldiers of Scottish descent formed a unit selected to spearhead the British response. As they approached the American outpost the Glengarries suddenly divided, some proceeding forward, the rest veering to the right into the bush screening the camp. The Yankee picket fired, reloaded and fired again-then scrambled to escape the bayonets of the foe who were by that time clambering up the side of the ravine protecting the position.

The encampment was in virtual turmoil Officers awaited orders-but Bissell seemed incapable of organizing a defence, and in no time the British were in full view, expecting a parade-ground battle. Bissell was, in fact, in no condition to command. His officers could hardly fail to notice something amiss in his behaviour, and the full extent of his nervous exhaustion would become quite apparent after the fray.

“They’ve got cannon…and rockets!” Now the American officers acted without orders-directing their men to take cover in the woods surrounding the camp on three sides. The cannon, a light six-pound fieldpiece, bellowed, and splinters flew as the grapeshot slammed into trees shielding the invaders. Then it was the turn of the rocketeers, who could no more than aim their terror weapon in the general direction of the enemy. Panic seized the soldiers cowering in the meaningless shelter of the woods as rocket snaked through the air toward them, for it was well-nigh impossible to predict where and when they would explode. When the blast finally occurred, lethal chunks of cast iron flew in every direction.

Take the cannon! The terse order would certainly mean casualties but there was simply no alternative for the Americans. Colonel Pinckney immediately directed his 5th United States Regiment to begin moving through the forest to the right of the British, hoping to outflank the enemy before being detected. But someone noticed shadows moving through the trees and instantly the cannon began slamming round after round of grapeshot in Pinckney’s direction.

While the British were momentarily distracted, American soldiers and dragoons opposite the cannon began emerging from the woods, forming for a charge. One unit, the 14th Infantry Regiment, had a particular score to settle from the humiliation of Beaverdams the year before. This would be a day of reckoning!

Now the tide of the battle had turned. Faced with imminent attack from the west and north, and with the high, steep bank of Lyon’s Creek on the south, the British had no choice. The bugle sounded retreat, and a quick but reasonably orderly withdrawal took place, back in the direction of the bivouac at the Lyon’s Creek Settlement. The Americans pursued to within a musket shot of the meeting house opposite Misener’s farmhouse before turning back.

Back at Cook’s Mills, details were ordered to bury the dead of both sides and to destroy the grain and flour mill-whatever could not be lugged to the camp at Black Creek. For days thereafter the mill pond displayed a thick crust of wheat, oats and corn. Confident the British had been thoroughly discouraged from further interference, General Bissell decided to stay put to await reinforcements and further orders.

Both arrived that night. The American force at Cook’s Mills now nearly equalled the effective fighting strength of General Drummond at Fort Chippawa-but on the afternoon of October 20th, Bissell ordered his entire detachment to return to Black Creek. It was a fateful decision if ever there was one. Had he crossed the Welland River, he could possibly have liquidated Drummond’s force, and gone to conquer the entire Niagara peninsula. But he pulled back, and the opportunity was forever lost.

Cook’s Mills was the last gasp of a ridiculous war that brought two years turmoil to the Niagara frontier. Most of the settlers of Crowland township were born in the United States; some had fought for the cause of American independence. Loyalism had not figured prominently as a reason for settling in Upper Canada, not for most. But the war, and in particular, the events of October 18th-20th of 1814, changed a lot of Crowlanders. They were Canadians.

I recall mother winding up the old gramophone

As we had no hydro there in our home

She said you’ll have good music in a little while

And to hear Ernie Tubb and others sure made us smile

The great speckled bird by Roy Acuff country music king

Yes it sure lifted our spirits to hear them all sing

I saw a lot of them in Toronto if they put on a show

From work I took a lieu day and to Massey Hall did go

And when folks had to keep food warm going to the fields

Towels were put in a box so the heat couldn’t yield

Go- carts were made of what people could find

And to ride them with no brakes took a contented mind

We didn’t have a go-cart so a buggy took its place

As we passed by the officer had a funny look on his face

If we met a car it was into the ditch and back on the road

Everyone was still on when we stopped yes a full load

Some machinery was repaired and sold once again

To save the cost of a new one and the farmer any pain

Many jokes were played on teachers some not too fair

Like letting her sit down with a tack on the chair

When it happened the strap she brought out

And to the guilty one she laid it on without a doubt

Movies were cheap but farm children seldom did go

As they had chores to do that we all know

Aprons were used to carry eggs and wipe away tears

But few are worn now like in the early years

Fire was a constant worry for people in a town

As all buildings were made of wood sand quickly burnt down

Measles and pneumonia are things the folks did dread

Each time I took sulfa tablets that brought me around

Yes for a few years now I’ve walked the ground

Winston E. Ralph

Bancroft, Ont.

Once again folks its January the first month of the year

May no one be glum but always filled with cheer

We don’t know what this new year will bring

Will it be something new or the same old thing

January is a cold month with only thirty-one days

Since its a new year now lets all change our ways

It originated before the year 1000 from Middle English

Coming from the Latin use of the word Januavius

In ancient Roman Culture Janus was a god of doorways

Also beginnings rising and setting of the sun some do say

His name is from the Latin Janus doorway or arcade

He went outside he didn’t stay in the shade

On Jan 1st we celebrate New Year’s day once again

So be careful on ice don’t fall and suffer any pain

For those born Dec. 22 to Jan. 19 your sign is Capricorn

Its Aquarius Jan. 20 to Feb. 18 for those then born

Some days will have a lot of ice and snow

And slippery roads will prevail wherever we go

There will be days this month that will be real cold

So bundle up in layers there’s no need to be told

Some folks may stay indoors as much as they can

As they don’t wish to be out with snow on the land

Youngsters will skate out there on the frozen pond

While others will play hockey as winter goes on

May snowmobiling be enjoyed as they glide over the snow

As I done in Toronto and other places back many years ago

Some will take snowshoes to walk over the ground

Since its the only way poor folk are able to get around

If you wish to hibernate put on a sweater and heavy socks

And use a warm blanket so the cold weather won’t shock

New Year’s resolutions folks don’t make anymore

Since to keep them would only make people sore

Winston E. Ralph

Bancroft, ON

Subscribe..

Subscribe..