Results for ‘Historical MUSINGS’

LOUIS BLAKE DUFF SPEAKER AT MEETING OF MEN’S ASSOCIATION

FIRST PRINTING PRESS IN NIAGARA PENINSULA IN OPERATION HERE

[Welland-Port Colborne Evening Tribune, 9 December 1931]

Fonthill, Dec. 9-Fonthill United Church Men’s association entertained 50 men to a hot supper, served by themselves, Tuesday evening, in the basement of the church. The United Church orchestra rendered stirring music. Will Barron gave a reading on Dicken’s “Little Nell.” The president C.W. Crowe introduced the speaker of the evening who in is inimitable style gave this history of Fonthill, saying this was founded and named by Dexter D’Deverado, after a place called Fonthill in Wiltshire, England. Mr. Duff stated the first printing press was located in Fonthill, publishing a paper called the Welland Herald. Many other interesting incidents relating to early days in Fonthill were related. W. A. Gayman and Rev. J.A. Dilts moved a vote of appreciation to Mr. Duff for his outstanding address. Mr. Smith of Chippawa, who is interested in the history of the peninsula was also heard, and Reeve C. Schelter expressed his appreciation of the evening’s entertainment.

Many articles of clothing for the kiddies were donated to help bring Christmas cheer to needy homes.

[Welland Tribune, 1 March 1947]

Louis Blake Duff addressed the Home Builders’ Group of Central United Church, in the basement of the church, following the evening service on Sunday, and he spoke on the very early days of printing. The theme was “How We Got Our Bible,” and Mr. Duff traced the history of the printing machines back to the first days. He stated that the world’s first printing press came into being between 1450 and 1455, at Guthenberg’s printing office at Maintz, and the very first book printed was a copy of the Old Testament. Before the end of the 15th century, there were printing offices all over Europe, and it was brought into being in England by William Caxton in 1477.

Dr. Russell Clark, president of the Home Builders’ Group, which comprises young married couples, occupied the chair. Mr. Duff was introduced by Frank Clute and the thanks of the meeting were expressed by Richard Seehuber.

[Welland Tribune, 5 November 1992]

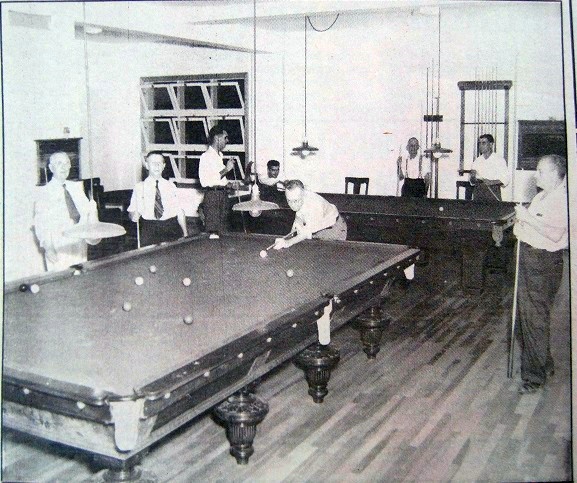

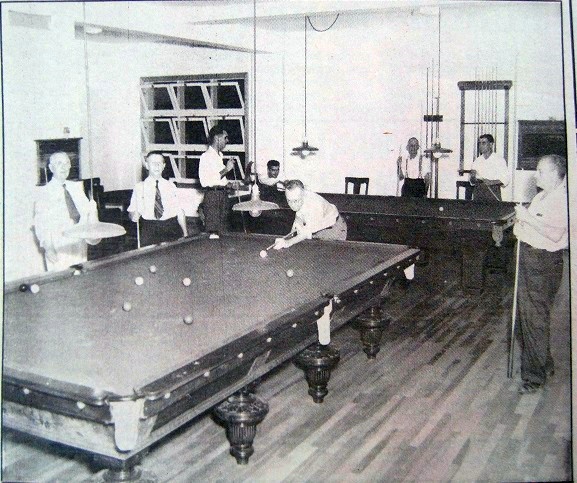

Billiard room scene in the 1940s in the old legion hall on E. Main Street, Welland.

[Welland Tribune, 5 November 1992]

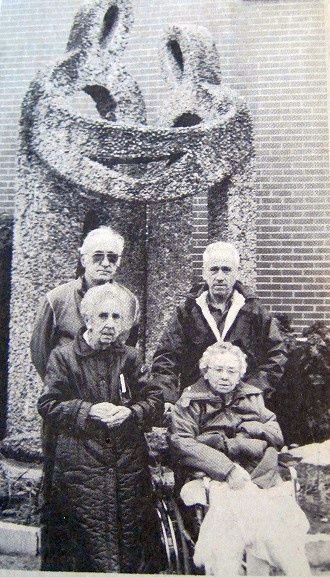

First World War veterans taken in 1979 at Vimy Night. All are now deceased.

By Paul Forsyth

[Welland Tribune, 24 January 1986]

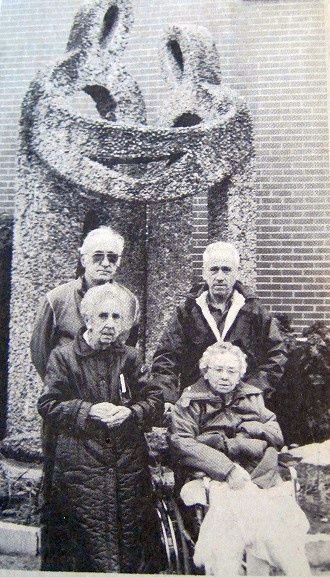

WELLAND- When Heinz Gaugel created a 16-foot high sculpture outside Sunset Haven Home for the Aged, he was trying to get a message across. Now 20 years later, the theme still radiates from the work.

“Has it really been 20 years?” asks Gaugel, who was unaware that this week marked the sculpture’s 20th anniversary.

[Standing in front of the statue are, left to right, residents May Quinn and Laura Campaigne. In the back are maintenance employees Walter Fogel and Dominic Trozzi.]

THREE MONTHS-The concrete steel and stone abstract work took him three months to complete in 1966, and was created to complement the modern addition of Sunset Haven.

“I selected stones from a quarry in Paris, Ont.-the greenish ones-because I wanted to have a contrast with the red brick wall behind it. It’s basically a steel frame covered with a strong wire, and cement put over it and the stones put in the wet cement.”

Gaugel, now 58, is world-renowned artist of many disciplines.

A native of Germany, he immigrated to Canada 35 years ago and has done artwork on a large scale all over the continent.

Included in some of his local works are a mural of the Last Supper inside Sunset Haven and a mural at St. Andrew’s Church.

SOMETHING APPROPRIATE-“The thing was to find something appropriate for the home of the aged. I felt the name-Sunset Haven-meant there was a need to project the feeling that people are protected and taking care of each other.

“It is an exchange of love and protection-the care of humanity.

That’s the general idea. It’s a man and a woman protecting each other and holding each other in the sunset of their lives.”

On the building behind the sculpture a setting sun is depicted, and flood lighting at night creates an interesting effect.

BEAUTIFUL SHADOW-“The two people in front cast a very beautiful shadow. It’s a little more dramatic than I expected it to be-I’m very happy with what’s been done there.

“I’m surprised after 20 years it’s still in mint condition, but I’m very happy about that.”

Gaugel gave no name to the sculpture-a belief he has with all his works.

“I never have named any of the things I have done. I don’t think names should be given-it limits it to some extent.”

Instead, he leaves names up to those in possession of his works.

By Robert J. Foley

[Welland Tribune, Date Unknown]

William Hamilton Merritt stood on the floor of his grist mill and watched the feverish activity as they attempted to get as much done as possible before the mill shut down. The level of the Twelve Mile Creek had been dropping steadily in the last week and soon the great water wheel would be high and dry. The shutdown could last for weeks or even months with the loss in business and the financial pressures that accompanied it.

To add to the pressure a monetary crisis was brewing in England that had begun to affect the business in the colony. Merritt had gone up to Montreal and had received a very low price for his goods because of the shortage of cash. Things looked gloomy for business prospects for the balance of 1818.

On his return from Montreal he found all the mills idle and a backlog of timber and grain to be processed. Merritt then resolved to pursue an idea that had been lodged in the back of his mind since his days of patrolling the upper Niagara River during the war. If he could dig a ditch from the Welland River to the head of the Twelve Mile Creek his water problems would be over. To pay for the project he envisioned a canal that also would carry boats to bypass the Falls of Niagara.

Taking the imitative, he went about the district gathering support for his proposal. The idea of a canal was not as revolutionary as we might think. This was the age of the canal. In Britain the young Duke of Bridgewater had toured the Canal du Midi in the Languedoc region of France in 1753. He was so impressed that he began to build his own canals in England using the French model. The Canal du Midi had been in operation since 1681. In the United States, two small canals had been built in the 1790s. The Santee Canal in South Carolina, 22 miles long with twelve locks was completed in 1822 with the Champlain Canal linking Lake Champlain with the Hudson opening the following year.

In the summer of 1818 Merritt, with his friends, George Keefer, a merchant and mill owner from Thorold and John Decew also from Thorold set out to make a rough survey of a possible route. With a borrowed water level belonging to a mill owner at the Short Hills the three set out. Starting from the south branch of the Twelve Mile Creek at present day Allanburg they proceeded due south to the Welland River a distance of two miles. They reckoned the dividing ridge to be 30 feet above the level of the creek. It was later proven that an error of 30 feet had occurred and the height was actually 60 feet. Merritt and his partners were not the only ones thinking canal in the peninsula. The inhabitants of Humberstone and Willoughby Townships advocated a canal from Lake Erie to the head of Lyons Creek. Bertie Township pushed for a canal to avoid the rapids at Fort Erie. John Garner of Stamford remarked that, “Locks may be made to pass the great falls and connect Lakes Erie and Ontario; but many years must elapse before the province is rich enough to afford the expense.”

The British government was also interested in a canal. The vulnerability of shipping should another war erupt with the United States was of great concern. Ships would have run the gauntlet of guns all the way to Queenston when coming from Lake Ontario and from Fort Erie to Chippawa on the other end.

The government was also planning to survey a route from Ottawa to Lake Ontario. The rapids at Lachine were being eyed as well. However, talking was one thing, building was another.

While others dreamed and talked, Merritt plans in hand, went into action. He approached the legislature for an appropriation of funds for a proper survey of his route. Sir Peregrine Maitland, the Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, having built a summer home at Stamford, was most interested in the project and lent his support to the scheme. The legislature set aside $2,000 for the purpose and hired an engineer by the name of James Chewett to do the job.

To Merritt’s dismay, Chewett scraped his proposal and embarked on a much grander canal scheme that was doomed to failure before it began. Chewett began his survey at the Grand River passing just west of Canborough into Caistor where it was to swing east into Gainsborough. It then swung north crossing the Twenty Mile Creek and descending the escarpment between Beamsville and Vineland. The canal turned west from there and following the escarpment, ended at Burlington Bay, a total distance of over 50 miles.

Although Merritt’s main motivation for a canal was one of water rather than shipping a new impetus for construction of a ship canal in the form of the Erie Canal. The Erie Canal began construction in 1817 to link Lake Erie with the Hudson River allowing goods from the upper lakes to move directly to New York City. The bulk of trade thus would bypass Montreal and Quebec leaving Canada a backwater in the scheme of continental business.

With the rejection of his proposal by Chewett, Merritt’s financial situation became critical and dark days lay ahead for him both financially and personally.

By Robert J. Foley

[Welland Tribune, 22 February 1992]

Life was hard for the ordinary farmers struggling to recover from the war of 1812. Many lived in isolation along the creeks that flowed into the Niagara from Willoughby and Bertie townships or into the Welland River from Wainfleet, Crowland and Humberstone. Rebuilding houses and barns drained what little capital they had. Most made due with the crude buildings that had all but disappeared as prosperity had come to the peninsula at the turn of the century.

The struggle to survive held the undivided attention of the entire family. Chores were complete before all else. As soon as a child was old enough to comprehend he or she was given a task, simple at first, but they picked up their share of the burden as they grew.

For us, who simply flick a switch when we want light or run down to the supermarket for our meat and groceries, it is hard to imagine having to plan carefully months in advance to light, heat and feed a household, but that is exactly what the pioneers had to do. One eye had to be kept on the wood pile. Was there enough to last the winter? Is it time to cut next year’s supply? Often if the farmer miscalculated he would have to burn green wood with the resultant smoke that inevitably would linger in the room.

The laying up of preserves for the winter was a necessary task for every pioneer housewife. The fall butchering and the preservation of meat was calculated to see the family through as well as to provide income from the sale of pork and beef to the military garrison and the growing towns.

All the cooking and heating in the pioneer house emanated from the big fireplace in the kitchen. The fire has kept blazing during the day in fall and winter as the door was often left open, despite the cold, for light and to clear smoke from the house.

For cooking purposes the fireplace was outfitted with an iron crane with hooks to hold pots. By swinging the crane out the meal could be checked without leaning over the fire. Baking was done either in a small stove fitted into the fireplace or in a crude oven built in the yard. Winter and summer the bread was baked in this manner; wood was piled into the oven and burned, effectively to preheat the oven. The ashes were scraped out and the bread inserted, cooking with the heat retained in the walls of the oven.

The utensils used in the kitchen were crude by our standards. They were often handmade from wood. Spoons, ladles and forks were laboriously carved by the man of the house. Bread pans for raising the dough were hollowed out of solid pieces of wood. The large, long handled wooden paddly used for putting the bread in and out of the outdoor oven was often cut from a single piece as well.

Health was another problem that plagued our forbearers in the 1820s. Fifty-five percent of the children did not live to age five. Doctors were often military surgeons located at the various forts around the peninsula. Doctors began to appear in the larger centres like Niagara and St. Catharines, but were too far away to be of use to most of the isolated farms and communities.

With the shortage of trained medical doctors it fell to the more educated in the neighborhood to fill the gap. These “folk” doctors, who were usually women, kept a supply of bandages and medicines obtained from the military surgeons on hand to treat their patients. They were often versed in the home remedies brought from Europe as well as those of the local Indians. These same women also acted as midwives and were sent for when the time for delivery of a baby was near.

Chronic diarrhea, dysentry and cholera, caused by the primitive sanitation, were the chief health problems threatening the populace. The local home remedy might be the only medicine available. For the above mentioned ailments this would include oak bark. The practitioner boiled an ounce of the inner bark in a pint of water and administer it to the patient. Acorns and blackberry root were also used with good results.

Children were in constant danger from diseased that are considered little more than inconveniences today. Measles and chicken pox were dangerous. Many children died of fevers brought on by teething.

Another danger facing the pioneer was the possibility of injury. Serious wounds resulting from chopping wood were fairly common. The treatment was to apply a court plaster, bind the wound tightly and hope for the best. A court plaster was made with isinglass, a gelatin concocted from the air bladders of fresh water fish and silk. Anxious watch was kept for any sign of infection that almost led to amputation of the offending limb. Before the age of anesthetics such operations were painful as well as dangerous.

The patient was taken to the nearest surgeon, usually Fort George or Fort Erie. Liberal doses of rum or some other alcohol were administered to dull the senses. Knives and saws were warmed up to lessen the shock and the doctor went to work. If the person were lucky they fainted at the first touch, sparing them the ordeal that the cutting and sawing would entail.

[Welland Tribune, Early No Date]

Visit the Welland Museum in the old Carnegie Library

140 King Street

Welland, Ontario

The Welland Museum, housed in a completely renovated schoolhouse, records the history of the city since the first settlers arrived.

The earliest inhabitants of the region were the neutral Indians, whose way of life is described in the museum. The Neutrals tried hard to avoid conflicts with other tribes but were eventually wiped out by the Iroquois.

Exhibits include pictures of one of their villages and maps showing where they were located. Chipping flints, scrapers and a stone knife found in excavations are displayed.

A corner of the museum where the story of the United Empire Loyalists is told displays an old spinning wheel, snowshoes, a cradle and a sideboard.

The first wave of Loyalists arrived in Canada because they were no longer welcome in the United States but was followed by a second wave composed mainly of settlers seeking inexpensive land. Records show that only about half had English backgrounds. Many had Dutch, German, French and other ancestries.

The building of the first Welland Canal brought a third major group of people to the region because, with the primitive construction equipment then used, many hands were needed to dig the canal.

The majority of the third group were Irish who had originally emigrated to the U.S. to help construct the Erie Canal. When it was completed they moved to Canada to build the Welland Canal.

The most interesting exhibits in the museum relate to the building of each of the four Welland Canals. Models show the section of the canal which passed through Welland as it has appeared at various times.

One showing it as it was when it was first opened includes a reproduction of an aqueduct constructed of white pine that carried the canal over the Welland River, leaving sufficient clearance beneath to allow the passage of boats using the river.

The model of the second canal shows it as it was when it was completed in 1845. A new aqueduct had been built of stone and a wooden swing bridge could be moved out of position by hand to allow boats to pass had been installed.

A third canal is seen as it appeared in 1915, with a new swing bridge called the Alexandria Bridge. It was opened to traffic in 1902 and was operated by steam.

A model showing the fourth canal indicated its appearance in 1935 after a syphon culvert had been constructed to replace the aqueduct. Six concrete pipes carried the river underneath the canal.

In 1973 the Welland Canal Bypass was opened and diagrams show how a 4-tube syphon culvert now carries the Welland River under the Canal Bypass.

Welland in Victorian times is represented in the museum by a furnished parlor typical of that era, complete with framed lithograph of Queen Victoria, an organ, a phonograph with cylindrical records, a showcase with typical crockery and glassware, a harp, a stereopticon and antique dolls. Press a button and you can listen to recordings made in that era.

Children visiting the museum enjoy the Whirligig. It is contraption of wooden toys built in 1978 by G. H. McWhirter, age 84 years. The little operating figures are all driven by a single electric motor.

At the rear of the museum there is a blacksmith’s shop and a general store with showcases made in 1890, now used to display artifacts dating from the last century.

By Gerald D. Kirk

[Toronto Paper, Date Unknown]

Mr. Kirk was the 2nd prize winner.

It wasn’t a village, much less a town, just a random collection of crude dwellings and outbuildings along two main trails that intersected at Calvin Cook’s mills. Lyon’s Creek, that gave power to the saw and grist mills, was swollen from the uncommonly heavy autumn rains that had made a morass of much of Crowland township. Now in mid-October wheat from surrounding farms was still in the process of being ground into flour and meal, some earmarked for the British forces camped at Chippawa.

Calvin had been hard-pressed to accommodate the multitude of farmers anxious to transform their grain into flour before the onset of winter. Two years of war had devastated much of the Niagara frontier, and most other mills south of the Welland River lay in ruins.

But as they worked, the millers cast anxious glances out of flour-dusted windows toward the road from Fort Erie, with that special anxiety civilians feel in the proximity of two frustrated and desperate armies. For days the settlement had lived in a constant state of alert, an alert sharpened by the sight of Brown Bess muskets issued to the farm boys guarding the mills.

It was less than an hour after daybreak. The grey smoke of cooking fires mixed with mist still rising from the Niagara and from the campground sprawled low and soggy on its west bank. Fewer men had turned out for reveille than the day before, and the grim shadow of dysentery now hung over the tent of commander, U.S. General George Izard. A large column of infantry and cavalry that had been formed up on the river road began crossing the log bridge over Black Creek, wheeling left onto the trail leading away from the river. Ahead lay the dismal tamarack swamp that Niagara folk did their best to avoid at the driest of seasons.

The horse soldiers led the way, and behind them the commandant of the expedition, Brigadier General Daniel Bissell. His orders were safely tucked into a pouch in his saddlebag, but the contents kept coming to mind: “proceed to Cook’s Mills…reconnoitre the area….destroy the grain and flour…await reinforcements.” Not mentioned on paper but an objective nonetheless was the capture of Misener’s Bridge and the bridge at Pelham/Thorold line, both strategic crossings over the Welland River. Both were in easy marching distance of Cook’s Mills. But what if something went wrong. The prospect of a retreat back across the tamarack swamp caused beads of perspiration to appear on Bissell’s forehead despite the coolness of the October morning.

The sun was already past its highest point in the sky when the American column finally reached the deeply rutted road to Cook’s Mills. Tired and hungry, the men squatted along the road on whatever dry object they had or could find, and munched the hard biscuits each carried in his knapsack. The pause was mercilessly brief, and soon the march was resumed. Less than two hours later the dragoons in the vanguard spotted smoke from the cabin chimneys of Yokum, Buchner and Cook.

Shots were fired by the militiamen guarding the causeway over Lyon’s Creek, but the small force of defenders scattered as the Yankee dragoons charged, sabres gleaming in the afternoon sun. The last to attempt to escape, militia Captain Henry Buchner was quickly surrounded by dragoons and forced to surrender. Women, children and the elderly peeked from their places of concealment to behold the astonishing sight of a seemingly infinite number of blue and grey uniforms flooding their settlement.

Orders were immediately issued to set up camp, and the soldiers began assembling the small tents that would shelter them for the next two nights. By dusk the fields opposite the mills were a sea of canvas, and the men were beginning to build fires to cook their evening meal of dried peas thickened with crumbled biscuits.

Suddenly, there was a commotion on the outskirts of the encampment as plucky farmwives belabored some soldiers for pulling down fence rails to use for fuel. To no avail; before long, most fences in the vicinity were only a memory.

Sleep would come hard for most of the American soldiers camped on the damp ground that chilly October night. Many were natives of southern States and not at all accustomed to the Niagara autumn. But their discomfort would be forgotten as the report of musket fire echoed form the direction of the outpost east of the mills.

The disturbance lasted on a few seconds, but it seemed like hours to the men crouching near the fires, gripping their muskets. Then the only sound was the whisper passing from group to group…”He was one of ours” Then an uneasy stillness returned.

Hardly had the stars and stripes been hoisted up the makeshift flagpole the next morning than green uniforms were spotted on the Chippawa road. Glengarries! Lightly equipped with short flintlocks designed for guerilla-style warfare, these hardy soldiers of Scottish descent formed a unit selected to spearhead the British response. As they approached the American outpost the Glengarries suddenly divided, some proceeding forward, the rest veering to the right into the bush screening the camp. The Yankee picket fired, reloaded and fired again-then scrambled to escape the bayonets of the foe who were by that time clambering up the side of the ravine protecting the position.

The encampment was in virtual turmoil Officers awaited orders-but Bissell seemed incapable of organizing a defence, and in no time the British were in full view, expecting a parade-ground battle. Bissell was, in fact, in no condition to command. His officers could hardly fail to notice something amiss in his behaviour, and the full extent of his nervous exhaustion would become quite apparent after the fray.

“They’ve got cannon…and rockets!” Now the American officers acted without orders-directing their men to take cover in the woods surrounding the camp on three sides. The cannon, a light six-pound fieldpiece, bellowed, and splinters flew as the grapeshot slammed into trees shielding the invaders. Then it was the turn of the rocketeers, who could no more than aim their terror weapon in the general direction of the enemy. Panic seized the soldiers cowering in the meaningless shelter of the woods as rocket snaked through the air toward them, for it was well-nigh impossible to predict where and when they would explode. When the blast finally occurred, lethal chunks of cast iron flew in every direction.

Take the cannon! The terse order would certainly mean casualties but there was simply no alternative for the Americans. Colonel Pinckney immediately directed his 5th United States Regiment to begin moving through the forest to the right of the British, hoping to outflank the enemy before being detected. But someone noticed shadows moving through the trees and instantly the cannon began slamming round after round of grapeshot in Pinckney’s direction.

While the British were momentarily distracted, American soldiers and dragoons opposite the cannon began emerging from the woods, forming for a charge. One unit, the 14th Infantry Regiment, had a particular score to settle from the humiliation of Beaverdams the year before. This would be a day of reckoning!

Now the tide of the battle had turned. Faced with imminent attack from the west and north, and with the high, steep bank of Lyon’s Creek on the south, the British had no choice. The bugle sounded retreat, and a quick but reasonably orderly withdrawal took place, back in the direction of the bivouac at the Lyon’s Creek Settlement. The Americans pursued to within a musket shot of the meeting house opposite Misener’s farmhouse before turning back.

Back at Cook’s Mills, details were ordered to bury the dead of both sides and to destroy the grain and flour mill-whatever could not be lugged to the camp at Black Creek. For days thereafter the mill pond displayed a thick crust of wheat, oats and corn. Confident the British had been thoroughly discouraged from further interference, General Bissell decided to stay put to await reinforcements and further orders.

Both arrived that night. The American force at Cook’s Mills now nearly equalled the effective fighting strength of General Drummond at Fort Chippawa-but on the afternoon of October 20th, Bissell ordered his entire detachment to return to Black Creek. It was a fateful decision if ever there was one. Had he crossed the Welland River, he could possibly have liquidated Drummond’s force, and gone to conquer the entire Niagara peninsula. But he pulled back, and the opportunity was forever lost.

Cook’s Mills was the last gasp of a ridiculous war that brought two years turmoil to the Niagara frontier. Most of the settlers of Crowland township were born in the United States; some had fought for the cause of American independence. Loyalism had not figured prominently as a reason for settling in Upper Canada, not for most. But the war, and in particular, the events of October 18th-20th of 1814, changed a lot of Crowlanders. They were Canadians.

BY Robert J. Foley

[Welland Tribune, 11 January 1992]

Nowhere in the country had the effects of the War of 1812 been more evident than in the Niagara Peninsula. Besides the destruction of Newark and St. David’s, the town of Queenston was heavily damaged. The mills of Bridgewater as well as others had been burned by the retreating Americans or their raiding parties.

The farmers probably lost more than any others in this conflict. Many fought in the militia regiments neglecting the work necessary to grow their crops and feed their families. Fences were pulled down for firewood by both sides and many barns and houses were burned by American raiders. Refuse pits dug in the fields made some acreage untillable for some time.

The primitive transportation system was also in tatters. Roads were rendered impassable due to the heavy transports that weaved their way back and forth across the area. Bridges were burned or torn up. In present day. Welland Misener’s Bridge was burned by the British to impede the advance of the enemy. Brown’s Bridge, which was built about 1795 to cross the Welland River at the foot of Pelham Road, was also destroyed, but somehow it escaped the fate of its eastern neighbor.

The task of rebuilding was a daunting one and to many, who had started from scratch just 20 odd years before, the thought of beginning again must have been discouraging indeed.

Major David Secord stood before the ruins of his home in St. David’s. Only the chimney was left standing and a few bits of charred furniture were recognizable in the rubble. He had also lost a store and a large barn to the marauding American militia.

There was no question but that he would rebuild, beginning again. It seemed to him that his whole life had been spent starting over. One bright spot, however, was the promise of compensation for losses immediately suffered due to enemy action. The funds were to be raised by selling properties forfeited to the crown by those who had gone over to the invaders during the conflict. Still Secord was worried about the length of time it would take to pay the claims.

David Secord’s family was fortunate to have relatives in the Queenston area to stay with until a new house could be built, but many of his neighbors were under canvas with prospect of spending the winter in deplorable conditions. Major Secord knew that once the patriotic fervor over the war declined that the government might be reluctant to hand out money to those who had lately risked life and limb to save the country.

Worse yet were the families of men killed or crippled in the fighting. What was to become of them? He mounted his horse and rode back toward Queenston pondering the future of his devastated community.

While the peninsula was struggling to regain its feet with the end of the war, William Hamilton Merritt had not been idle while a prisoner of war. He took the opportunity to rekindle his friendship with the family of Dr. Prandergast of Mayville, New York, and in particular the good doctor’s daughter Catherine Hamilton, as he was usually called. Had met them when they lived near DeCew Falls and a budding romance had sprung up between the two. The romance had resulted in an engagement just prior to the move of the Prendergasts to Mayville just before the war.

With Merritt’s capture and confinement in Massachusetts for eight months he was able to communicate more frequently and on his release he headed to Mayville where he was married to Catherine on the 13th of March 1815. Merritt arrived in Buffalo with his new bride on a cool spring evening. They had come from Mayville on roads of upstate New York. Buffalo was in the process of being rebuilt and the sounds of hammers and saws filled the air with their symphony. The destruction caused in December of 1813 was disappearing under an onslaught of new lumber.

They moved on to Black Rock to await the ferry to take them across to Fort Erie the following morning as Hamilton was anxious to get home after so long an absence. The Merritts rode into Shipman’s Corners in the middle of the afternoon. The settlement along the Twelve had escaped the fate of St. David’s and had come through the war relatively unscathed. Its strategic location on the main Niagara-Burlington Road should have made it a prime target, but although some of its inhabitants were taken prisoner, including Hamilton’s father, Thomas, the buildings were spared. Merritt felt the warmth of home as he passed the church and approached Paul Shipman’s Tavern to the greeting so many of his acquaintances. They remembered Catherine from her previous stay and made her welcome. After they have been coaxed into the Tavern for a toast they headed out to the old family homestead on the Twelve Mile Creek.

William Hamilton Merritt spent a few months trying to decide what lay in the future for him. The one thing he knew for certain was that his military experience left him ill-suited for the quiet life of a farmer. The thought slowly formed.

In his mind that perhaps business was his calling. Goods of every kind were in short supply and if he could make use of the connections he had made during the war, perhaps he could become a merchant in the district. With the destruction of so many mills in the Peninsula there was money to be made there as well. He soon fixed his sights on such ventures and began to lay his plans to see them through. That decision changed the history of the Niagara peninsula forever.

Historical Notes: (1) The Bridgewater Mills were located on the Niagara River near Dufferin Islands. (2) Misener’s Bridge carried present day Quakers across the Welland River. The crossing disappeared with the building of the canal. If you go down to the foot of the Pelham Road when the waters of the Welland River are low, you will see five of the original pilings of Brown’s Bridge. They have been services of our past for 196 years.

Subscribe..

Subscribe..