Results for ‘Historical MUSINGS’

By Eva Elliot Tolan

[There are many such articles by this historian in the Niagara Falls Library, digital collection, but this one that I found in my mother’s file is not there, circa 1950s’. Margaret Gonder, wife of first Welland citizen David Price, is my ancestral grandmother.]

Last week we had the privilege of visiting one of the very few old homes still remaining in the Niagara district. This was the old Gonder house on the Upper Niagara River, now the home of Mr. and Mrs. J.A. McTaggart.

Michael Gonder, the original owner and builder of this fine old house, was a Loyalist from Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. He had tried to remain neutral during the War of the Revolution, but was so persecuted by the rebels, even to the extent of having his buildings burned, that he finally decided to migrate to Canada.

Michael’s wife, Eva Snyder, sometimes referred to as “Rebecca,” refused to leave her Pennsylvania home, so she and her husband divided their four children between them, she keeping the two fair ones and he bringing the two dark-complexioned ones to Canada with him-these were Margaret and Jacob.

The Gonders stayed for a while at Niagara, (Niagara-on-the-Lake) waiting to buy a suitable piece of land. John Rowe, a resident of Stamford Township and former soldier in Butler’s Rangers, had received as part of his land grant, Lot 6 on the broken front of the Upper Niagara River, opposite Grand Island. This Michael Gonder purchased. He was classed as a “later” or “treasuery “Loyalist, because he purchased his land, instead of receiving it as a reward for military services, as did the original United Empire Loyalists. The later Loyalists, however, were also required to take the oath of allegiance to the British Crown before being given their deeds to their land.

On his land on the Upper Niagara River, Michael Gonder built what in those days was a very imposing dwelling in contrast to the usual log homes of the first settlers. It was built of stone, but some subsequent owner had the stones covered with stucco, this altering its appearance. The interior, too, has been altered by successive owners one of the most regrettable changes being the removal of the old fireplaces. However, in the attic and cellar may still be seen the huge hand-hewn oak timbers, marked in many places with the mark of the axe. The windows and doorways are wide and deep, indicating the thickness of the original stone walls.

At the back of the house on the second floor was the long, narrow loom room, home of that period when so much hand-weaving was done.

There were eight bedrooms in the old house, which, in early days was a favorite stopping place for immigrants and other travellers going west. The Gonder house was always open for these _.

During the latter part of the war of 1812-14 the Gonder house was used by General Drummond as his military headquarters. At one time, in later years, it was also used as a temporary barracks for soldiers stationed on the frontier.

While the Gonders were still staying at Niagara, Margaret, the daughter, had met and fallen in love with a man forty years her senior. This was David Price, an interpreter in the Indian Department. Naturally the father frowned on this affair but the couple had decided to elope at the first opportunity. Accordingly, after they were settled in their new home on the Upper Niagara River, Margaret’s father and brother went over to Grand Island to attend to some cattle they had pastured over there. A man came riding along the River Road with a white handkerchief tied around his arm. Br pre-arrangement Margaret wore a white sunbonnet as she worked outdoors in the garden, to indicate she was alone. So the couple rode away to Niagara to be married by Rev. Robert Addison of St. Mark’s Church. This was in 1800.

But as time went on all was forgiven. David price had acquired a farm on the Welland River on the site of the present city of Welland. Michael, leaving his Niagara River property to his son, Jacob Gonder, in his later years went to live with his daughter, Margaret and her husband, David Price. When death finally claimed this old pioneer he was buried in the family burying ground on the Price farm, on the banks of the Welland River.

One of the Gonder girls of a later generation married a Sherk, so in time, the Gonder farm on the Upper Niagara became known as the Sherk place, and is still known by that name today among older residents.

Three-quarters of a mile back from the river, on the Gonder farm is the old Gonder family burying ground, where many of the Gonder family were buried. One of the old-gravestones marks the last resting place of Jacob Gonder. Jacob, as a young lad, came with his father Michael to live on the Niagara River. He was born in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in 1776, and died here in 1846. Here also is the last resting place of Jacob’s son, Michael Dunn Gonder, and his wife, Mary Ann Wait. The latter was a niece of the notorious Benjamin Wait, a resident of the Short Hills area, who, for a number of others, was sentenced to die for their share in the Rebellion of 1837-38. His sentence was finally commuted and he with a number of other, was banished to the penal colony in Van Dieman’s Land, for which he escaped some years later, returning to his home and family in Canada.

[Evening Tribune, 27 March 1968]

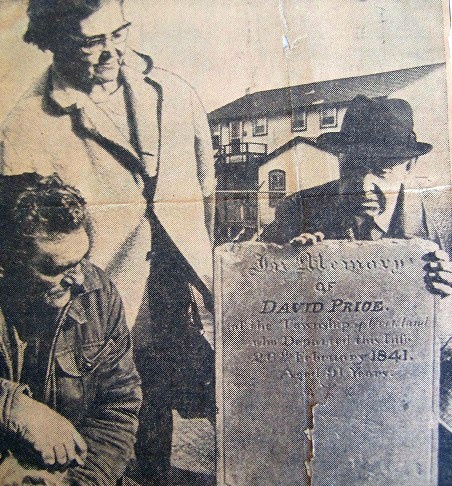

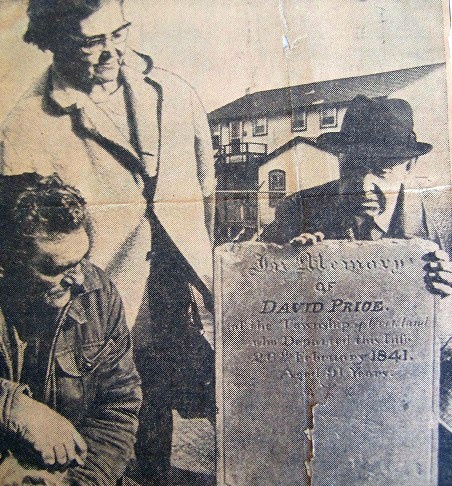

An interesting item from Welland’s early history has come to light as the result of an item in the Tribune’s Centennial Edition printed last year. About three years ago a city employee, Albert Albano, 279 McAlpine St., was doing some excavation work for a water main break at the northeast end of Dennistoun St., just past Welland High and Vocational School when he unearthed an ancient tombstone and brought it to the city yards.

He had been working in the site of Welland’s earliest cemetery. Many years previously those who rested there has been removed to the Anglican Cemetery. He didn’t know at that time that that the tombstone was that of Welland’s first white settler, David Price.

Two years later he read an historical sketch in the Tribune about early settler and he had intended to contact the author, Mrs. E.A. Hurst of Hamilton. He finally mentioned the find last Sunday night to Crowland Township historian, James Morris, of White Pidgeon, who got in touch with descendants of that family.

The stone reads, “In memory of David Price of the Township of Crowland, who departed this life 26th February, 1841, age 91 years.”

Family members have expressed the hope that this head-stone can be placed in some place where it will add to the historical interest of the area.

PRICE HISTORY

About 1768, David Price was kidnapped by Indians of the Seneca tribe, following a massacre in which his parents and some members of his family perished.

He was adopted into the tribe and learned the ways of the Indian and when he had achieved manhood, he made his way back to the white settlements on the Niagara Frontier.

Friendly Indians took him to an excellent spot to homestead on the Chippawa and he settled close by what is known as Welland River in the area of the high school.

His knowledge of Indians and their ways made him invaluable to the government as a reward for his services he was given a crown grant for that area which is now the city of Welland.

It is believed that the original grant is now held by Barry Wade in care of the Wade Estate.

- Photoraph: Albert Albano with Mrs. Harold Gent, Beckett’s Bridge and Emanuel Hurst.

ISSUE NOT LAID TO REST YET

By Greg Dunlop

[Welland Tribune, 30 July 1986]

PELHAM-A report from the Pelham Historical Society has been unable to put the Hillside Cemetery/Dawdy Burying Ground to rest.

Last autumn the society agreed to a request from the Pelham town council to research the history of the Canboro Road Cemetery .Council had been approached by a descendent of the Dawdy clan who the Hillside Cemetery had been renamed in contravention of a 60-year old agreement and that the graveyard’s original name should be restored.

Council members decided they didn’t have enough information to base any decisions on so they asked the Historical Society to investigate the matter and try to clear up a few questions. The society’s report was ready last week and President Mary Lamb presented it to council.

Lamb said even after all their work there were still some grey areas.

“I’m surprised we haven’t been able to find more information. It’s hard to believe there isn’t someone in town who remembers where, when and why the names was changed.

The society circulated requests or anyone with information to come forward but even with the public input the facts were difficult to nail down for certain.

“The cemetery board’s records are critical but they’re not around. No one seems to know what happened to them.”

So far the society is only able to peg the name change as happening sometime in 1933. Lamb said she went through old Welland Tribune clipping to see when the graveyard was first referred to under the Hillside name.

“I went through the death notices fo all of 1933 and they referred to the Dawdy Burying Ground but the first death notice I found for that area in 1934 called it the Hillside Cemetery with Dawdy written in brackets.

She said it was unusual the change was never reported in the newspapers of the time because they use to publish much less critical information. Anything of any significance was published back then, according to Lamb.

The society never did find an agreement between the town and the cemetery trustees where the town agreed not to change the cemetery’s name after they took it over in 1926. The graveyard had been known as Dawdy’s Burial Ground from the early 1800s until 1933.

Lamb told council the society had done all it could, and unless someone else came forward with more information there was nothing more to add. Mayor Bergenstein thanked Lamb and the Historical Society for her efforts.

Council decided to give Tony Whelan, the man who brought up the whole issue, a chance to study and comment on the report before making any decision.

They requested Whelan to prepare his comments and information in written form and to present it at the next meeting of council, August 18.

[Welland Tribune, 30 July 1986]

PELHAM-Tony Whelan thinks his family has been done an historical injustice and he is determined to see it get right.

Whelan, a member of the Dawdy clan, says the town of Pelham broke an agreement to keep the Dawdy Burying ground name when it was changed to the Hillside Cemetery in 1933. The graveyard along Canboro Road near Effingham Street was taken over by the town in 1926 and he claims the agreement was made then.

Whelan said he learned of the agreement between the town and the cemetery’s trustees from his grandparents.

“When I three or four years ole I would visit people along with my grandparents and I would hear them discussing the issue.”

He said it stuck in his mind and last year he finally checked the record had to be set straight. Whelan approached the town last fall and presented his research. He asked that the Hillside Cemetery should be renamed back to the title it had since the early 1800s’.

Whelan said the renaming would acknowledge his family’s place and role in Pelham’s history. “There are parks and streets named after politicians and others for their community service. I just want the same thing.”

He said he is not alone in his battle but has numerous other clan members backing his efforts. He expects 50 of them to attend a meeting with Pelham town council on August 18when the issue will come up again.

The Dawdy Clan can trace their Canadian roots back to the year 1800 when Jeremiah and Susanna Dawdy moved to Pelham from New Jersey. They purchased 175 acres of land in the area of what is now known as Canboro Road and Centre Streets.

When Jeremiah died he was buried on the family farm, thereby creating the Dawdy Burying Ground. His family and descendants continued to grow and prosper in Pelham. Whelan says they were never community leaders or politicians but simple hard-working farmers.

As they died most of the Dawdy clan were laid out beside their forefathers in the same graveyard. Whelan said there are now more than seven generations and 130 descendants buried there..

Over the years the graveyard expanded and non-family members were buried there as well. The Beckett family became associated with the cemetery and many of their family descendants were buried there. There are reports the cemetery was known as Beckett’s Graveyard at one time but Whelan disputes this and the facts are debatable.

TRUSTEES

A board of trustees took over the administration of the site in the early 1800s and continued to run it right up until 1926 when the town assumed the responsibility.

Whelan said the town never filed a deeming bylaw and therefore it doesn’t even actually own the cemetery, “Not that we want it. All we want is the historical name back.”

He has still yet to find a document which can prove the existence of the agreement to keep the Dawdy name but he said the weight of the historical evidence he has accumulated is more than enough to prove his case.

“I won’t take no for an answer now. There are just too many facts for this case to be ignored. He said he is willing to take the case as far it has to go to see the name changed. “

Right now Whelan is preparing for the first round on August 18 when he will have a chance to speak before the town council.

[Welland Tribune, Date Unknown]

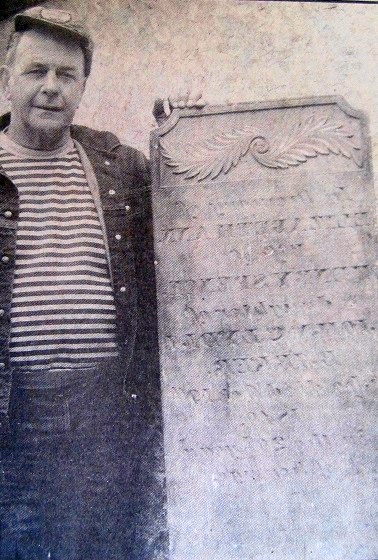

WELLAND STAFF: City Council tomorrow night will order a title search on the old Price Family Cemetery on Colbeck Drive, but Anthony Whelan says he already has proof the 144-year old cemetery is city property.

Whelan, a local amateur genealogist who is pressing the city to restore and maintain the tiny cemetery, found documentation at the Welland Land Registry office showing its ownership was transferred to the city in 1960, possibly as part of the land annex for the construction of a nearby bridge that has since been dismantled. It took him an hour and a half, he says.

George Marshall, chairman of the parks, recreation and arena committee, says the city will fulfill its responsibility under the Ontario Cemeteries Act if a title search indicates it must.

The cemeteries Act makes all owners of cemeteries responsible for keeping them in good condition. When a cemetery is unowned, it becomes the responsibility of the municipality in which it sits.

At a closed meeting on Oct. 22, the parks, recreation and arena committee voted to order both a title search and a “clean-up” at the cemetery.

The recommendation will be before council on Tuesday, and Marshall says city workers will be sent to begin clearing the site soon after.

He did not suggest a date, however, added the matter is to be reviewed by city solicitor Barbara Moloney.

The cemetery-now overgrown with weeds and bushes, most of its headstones beneath the soil and its fence all but fallen down-is one of two cemeteries used by the descendants of David Price, thought to be the first white settler in Welland, The other was long ago pushed aside to build homes near Denistoun Street and the Welland River.

The only visible headstone at the cemeteries bears the name of Sarah Hutson, a member of the Price family who married a man named James Hutson.

She was buried in July, 1886. The first record burial at the site took place in 1842, although Whelan suspects Elisha Price, the first member of the family to own the property on which the cemetery is located, is buried there with his wife. Elisha Price died in 1824.

Whelan has done considerable research on the cemetery and views it as an invaluable piece of Welland’s history.

He is angered that it has been left to fall into its current state, feeling the city has been reluctant to devote money to taking care of the cemetery, while spending much larger sums of money on projects of lesser importance.

Between August 1973 and April 1975, city council and the parks committee dealt with the matter without significant results.

A chronology of the matter compiled by city staff shows a series of recommendations, letters and motions that trailed off on April 1, 1975, with an apparently unfulfilled council instruction to the city solicitor for a title search to be conducted.

“This has gone on before,” Marshall admitted this week.

“I guess it just drifted away, as some issues do.”

He said, however, the parks committee would take steps to see the city’s responsibility under the Cemeteries Act, if it can be established, is fulfilled.

“It’s clear in the Cemeteries Act,” he said. “It certainly appears to be our responsibility.

“It’s one of the first cemeteries in Welland, so it obviously has some important historical merit.”

Whelan has the backing of the Welland Historical Society, which voted recently to support his effort with the city.

“The pressure has to be kept on,” he said recently, vowing to do so until he sees the cemetery well maintained. The money required to do so, he claims, would be comparable to the roughly $1,600 which will be devoted to staging the opening of the renovated farmer’s market next month.

There’s an urgency now, because a lot of this stuff is disappearing,” he says.

“I feel that urgency.”

By Robert J. Foley

[Welland Tribune, 13 April 1992]

The spring of 1825 brought new life to the Irish laborers who worked in the deep cut. The ankle deep mud was better than the bitter cold of the winter for those shovelling their way to the Chippawa. The teamsters cursed the muck, however, as their horses strained to keep the heavy wagons moving.

There were sections where the muck had to be carried to the top by hand. Men with hundred-pound sacks on their shoulders struggled up the slippery slope to load wagons that would get bogged down in the bottom. Many a man lost his footing and tumbled back to the mud below. If her were lucky he lifted the sack to his shoulder and started again, but many were injured, losing their jobs. There was no such thing as workers’ compensation to feed the sick and injured. No work, no pay was the cruel reality that they faced each day.

The canal was divided into 35 sections. Each section had a foreman. Fifteen laborers and six teams of horses. Some of the laborers worked with picks to loosen the earth while the others loaded the wagons with shovels.

John Phalen wiped the perspiration from his eyes that ran down from his hairline despite the cool temperatures. He leaned on his shovel for a moment while the foreman inspected the rock that impeded the work.

Phalen knew that if he were caught resting he would get a tongue lashing. The pain in his side that had kept him in agony for weeks was under control thanks to another laborer with knowledge of such things.

Phalen was suffering from a rupture, but the fellow had been able to fix him up with a crude truss that gave him some relief. He had to keep working for the sake of his wife who was expecting a baby any day. With two other children to feed, he could not afford to lose any time.

The foreman came away from the large boulder muttering about delays. The rock would have to be blasted with gunpowder.

“Phalen, get the drill, we’ll have to blast this one. Larkin, go and draw the explosives.”

Phalen shuddered as he pulled out a hand drill from one of the wagons. Blasting rock was always a tricky business. Just last week Frank Murphy, who lived tow shanties down from him had been blown to bits when the charge had gone up in his face. He had been the one to take the news to his wife.

The men took turns to drill a deep hole that would shatter the rock into manageable pieces for loading onto the wagons. This did not mean a respite for the others, however, as the foreman, constantly aware of the deadline for completing his section, drove them on, digging around and beyond the offending morsel of granite.

Finally the hole was pronounced deep enough and the crew was ordered up to the top out of harm’s way. The only man to be left below was to be Patty Larkin to set and light the charge. Phalen could see the glassy look in Larkin’s eyes. He had taken on too many sips from the “water” boy’s bucket and was half drunk. In his condition he stood a good chance of going up with the rock. Before he could think, he heard himself say, “Let me do that Patty, you get up top with the others.”

Phalen turned away from the look of relief on Larkin’s face. He began to place the charge carefully in the hole trying not to think of Murphy’s crumpled body lying in the mud. He lit the fuse and ran for the slope climbing for his life. Half way up the pain struck him like an axe and he slipped. For a moment he couldn’t move. He was sliding back down toward the bottom. The men at the top must have sensed a problem for despite the danger, several heads popped over the edge and began to call to him. “Hurry, John, hurry.”

Phalen struggled to reach the lip of the ditch in spite of the pain. As he neared the top, several hands grabbed him and pulled him over just as the thundering explosion shattered the air.

Phalen lay on his back gasping for air. The pain in his side was only a dull throb now. The foreman stood over him. “Are you all right, Phalen?”

“I’m fine, just slipped that’s all,” he lied.

“Well then, get off your back and start loading up that mess you made down there,” he said, a rare smile on his face. Maybe the foreman was human after all.

The backbreaking work of excavating the deep cut was carried out under conditions that we would be unable to comprehend. The cut was an average of 44-feet deep in the 1 ¾ mile stretch between Allanburg and Port Robinson.

In July, 1826, a newspaper advertisement offered wages of $10-$13 a month and boasted that only three deaths had occurred in the previous month. Single men could rent a room at a boarding house for $1.50 per week. This amounted to half their pay. A man with a team was paid a few dollars more. The men with families built shanty towns along the route picking up and moving as the work progressed.

Because of the lack of safe drinking water the “water boys,” that moved up and down the line carried buckets of raw whiskey. This thirst quencher was ladled out in tin dippers. As a result of this, accidents and violence were common place.

Disease was another problem facing the workers. Bad water and poor sanitation bred cholera, dysentry and a myriad of other maladies that killed the men and their families by the hundreds.

The Welland Canal was not built by the merchants, bankers and investors. It became reality by the sweat, blood and lives of thousands of men, mostly Irish immigrants seeking a better life for themselves and their families in a vibrant young country that was to become Canada.

It was make-or-break time as farmers eyed the weather

By Robert J. Foley

[Welland Tribune, 9 March 1992]

The most critical time of the fall for the farmer was the harvest. On this hinged his livelihood and the survival of his family. Would an early frost damage the crop? Would the rains hold off until the fields were cleared? All these things plagued the pioneer as he waited for his crop to open.

In preparation for the harvest the equipment had to be inspected and repaired where necessary. Sickles and scythes were sharpened and flails made ready. Sweeping the barn floor to prepare it for threshing was a job for which the children took responsibility.

With one eye on the weather the farmer walked his fields checking the grain to satisfy himself that it was ready for harvesting. If he didn’t have children old enough to help with the cutting and gathering, he would hire some farm laborers from the nearest town or, if the weather was holding, neighbors gathered and helped each other bring in the crops.

Haggai Skinner looked over the flowing field of wheat that was about to be cut. He let his mind wander over all that he’s been through in the last seven years. He had been working this very field in 1813 when the American patrol had snatched him up and made him a prisoner-of-war. It angered him still when he thought it. At 64, he was exempt from militia service, yet they had taken him anyway. For almost a year he had languished in prison to be repatriated in July, 1814, in time to hear of the bloody battle at Lundy’s Lane. He arrived home to find the family in mourning for Timothy Skinner who was killed at the Battle of Chippawa earlier in the month. He was buried somewhere on the battlefield. The American refusal to allow the recovery of the dead after the battle was something else that rankled Haggai. He had gone to the battle site after the harvest that year in a vain hope of finding a clue to the burial spot, but found nothing.

He was roused from his musings by the impatient stamping of the horses who seemed anxious to get started. Seeing the boys ready to gather the cuttings into sheaves he began to swing his sickle in a smooth, rhythmic stroke developed over 60 years of farming.

As the grain was cut the workers following behind gathered them into sheaves and loaded them on the wagon for transport back to the barn. The work day began at first light and except for meals, went straight through until sundown. Often lunch was brought to the fields so as to lose as little time as possible.

Once cut, the grain was moved to the barn for flailing. The flail was made up of two sticks each about three feet long. A leather strap or a piece of rope joined these together. The grain was laid out on the floor and the men began beating the stalks to separate the grain. Once this was completed, the stalks were gathered, shaken and discarded.

The grain was swept into a broad wooden shovel with a handle on either side. In a process called winnowing, the grain was tossed in the air, allowing the chaff to blow away while the heavier grain fell back into the shovel. We can imagine the field day that the farm poultry had snatching up the grain that invariably fell to the ground. The grain was then bagged for the trip to the mill or to sell as whole grain.

Wheat most often went to the mill to be ground into flour. Oats and barley were usually sold for feed or, in the case of barley, to be made into beer or liquor at one of the local brewers or distillers.

Transportation to the market was a thorny problem in the 1820s. In Humberstone and Wainfleet, the mills at the Sugar Loaf had to be reached over swampy terrain. In Stamford, the Bridgewater Mills, burned by the American in 1814, had not been rebuilt, making the long trek to either the mills in Thorold or to the Short Hills.

If heavy rain fell, the roads became impassable and often the crop had to be moved in other ways. Those on a waterway sometimes tried to float the grain to the mill, however, this often led to a soaking leaving the grain useless for milling.

The mills in the Niagara Peninsula were water-powered. The grain was poured into a hopper and was grounded between two large stones. The flour dropped through a meal trough and was packed in barrels for storage and shipment. Payment for the milling was often made by giving the miller share of the grain. The miller would also would act as the farmer’s agent in the sale of the ground grain as well.

In order to produce an adequate grade of flour the mill stones had to be sharp. It was necessary from time to time to deepen the furrows in the wheel and to dress the surface. A crane was used to lift and turn over the upper stone. The furrows were then deepened with steel picks to bring them up to spec. To test the levels of the stone a wooden bar with its edge smeared with red clay was drawn across the surface. The high parts with red clay smeared on them were then dressed off until the surface was level.

The next problem facing the millers and merchants of the peninsula was moving the flour to market. Produce from Humberstone and Wainfleet moved by water down the Welland River to Chippawa and then along the Portage Road to the busy port of Queenston. From here freight for every type was loaded on sailing vessels for York, Montreal and Quebec City.

*Historical Note; Haggai Skinner’s farm was located in Stamford Township in the vicinity of present day Mcleod Road and Drummond Road.

[Evening Tribune]

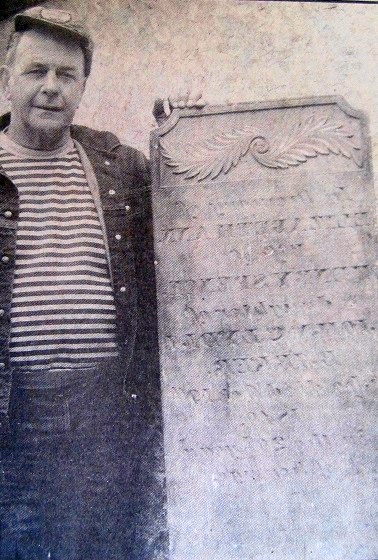

A tombstone dated 1840 and bearing the inscription of Elizabeth Ann Spence, wife of Henry Spence, was unearthed by Gerald Parker yesterday as he was tearing down a garage to construct a parking lot for an apartment house he owns at 102 Maple St. Parker considers the stone a rare find, but wonders why it was located on his property since he has no knowledge that a cemetery was ever located there. The stone identifies Elizabeth as the daughter of John and Lydia Barker and says she died Oct. 13, 1840. Parker said he intends to preserve the stone and perhaps donate it to the Welland Historical Society.

A tombstone dated 1840 and bearing the inscription of Elizabeth Ann Spence, wife of Henry Spence, was unearthed by Gerald Parker yesterday as he was tearing down a garage to construct a parking lot for an apartment house he owns at 102 Maple St. Parker considers the stone a rare find, but wonders why it was located on his property since he has no knowledge that a cemetery was ever located there. The stone identifies Elizabeth as the daughter of John and Lydia Barker and says she died Oct. 13, 1840. Parker said he intends to preserve the stone and perhaps donate it to the Welland Historical Society.

*There is an Elizabeth Ann Spence (Barker) buried In Drummond Hill Cemetery, 18 October 1840. Her husband is listed as Henry and her son John B. . Interesting !!!!

By Robert J. Foley

[Welland Tribune, 9 March 1992]

In the early 1820s the peninsula was still struggling to re-establish the industries decimated during the war. A deep recession that followed the conflict slowed the process greatly as we have seen in the problems encountered by Merritt.

On the site of the Battle of Lundy’s Lane a small community began to grow. Austin Morse was a furniture maker and undertaker whose chapel still operated on Main Street today. Andrew Moss made cabinets, James Skinner was a harness maker, John Misener ran a wagon building operation and William Gurnan was the indispensable blacksmith.

One of the more prolific endeavors of those days was the distillery. One such operation was located at the foot of Murray Street in Queen Victoria Park. It was a stone structure and was there to take advantage of the spring that ran down the ravine. It was abandoned in 1826 and eventually housed Barnett’s Museum.

St John’s, near Fonthill, was one community that had escaped damage during the war and prospered. It boasted many mills and a number of distilleries. An iron foundry, tannery, saddle maker, a woolen factory and many others rounded out this thriving town. The Welland Canal put St. John’s into decline as industry moved closer to the canal banks and today little remains of its former glory.

In the southern part of the peninsula the Sugar Loaf sported a community that included saw mills and grist mills. It also had a blacksmith, harness maker, furniture maker and the inevitable distillery.

One of the most important workmen in the community was the blacksmith. The first thing pioneers demanded upon arriving in the peninsula in 1781 was the services of a good smithy. We always associate the blacksmith with shoeing horses, but his business went far beyond that. He made everything from door hinges to wagon wheels.

The blacksmith shop was a miniature factory. The heart of the shop was the forge that was made of brick. It was set on a stone foundation with a square brick chimney that went up through the roof to a height of four feet above the ridge pole. The hearth was a square box 12 inches deep set next to the chimney. The bottom of the hearth was a slab of iron with a hole in the centre to take the air nozzle or tuyere as it was called. The tuyere was a hollow, slotted iron bulb attached to a pipe leading to the bellows. Air could be directed to one side of the hearth or the other by the use of an iron rod that rotated it. The brick work was extended to form a table on which the smithy could organize his work or leave finished pieces to cool.

The bellows was a huge leather lung eight feet long and four feet across that was mounted behind the chimney. A large stone was placed on the top so as to create a constant pressure allowing a gentle stream of air to keep the coals hot. If the smithy needed a little extra heat he pulled vigorously on the wooden handle that was attached to a chain and extended to the front of the forge.

If the forge was the heart of the shop then the anvil was the soul. It was a 250-pound block of iron that measured 5 inches across, 20 inches long and had a 16-inch horn curving out from one end. Its top was a slab of steel wielded to the wrought-iron base. Two holes were cut in the rear part or heel of the anvil. The hardy hole was square to fit the many forging tools used by the smithy. The pritchel hole was three-eighths of an inch and round. It was used for punching jobs such as knocking nails out of old horseshoes.

The placement of the anvil was very important. Because the iron had to be heated at least once, if not more, the anvil had to be close to the fire. It was usually placed with the horn facing the fire. The height of the anvil was also critical. The black-smith custom-fitted his anvil to match his needs. If it was too high he would wear himself out swinging his hammer; if too low his hammer would not strike the iron squarely ideally, the bottom of the smithy’s natural hammer swing matched the height of the anvil.

The setting of the anvil was an exact science, for once in place it could not be moved. It was mounted on top of a post that was sunk four or five feet in the ground. With his anvil in place and coals glowing red in the hearth, the blacksmith was ready to do his work.

The iron that the smithy worked came from a bloomer furnace and showed a crystal structure. After forging, the crystals formed a grain that allowed the iron to bend without breaking.

The blacksmith often had to draw the iron to make it thinner and wider. Heating the iron until it was red hot, he then swung it to the anvil and struck it with his set hammer until it was no longer pliable enough to work. He would repeat the heating operation until he was satisfied that he had a workable piece of material.

The peninsula was coming of age, The Welland Canal was about to come a reality to change the loves of all who dealt in its shadow.

By Robert J. Foley

[Regional Shopping News, 11 April 1990]

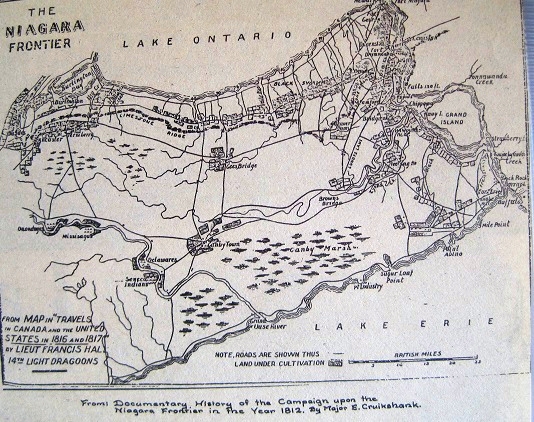

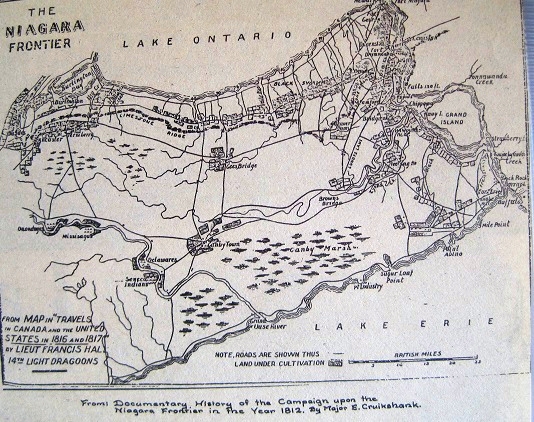

From Map in “Travels in Canada and the United States in 1816and 1817” by Lieut. Francis Hall 14th Light Dragoons.

MAP

At the foot of South Pelham Street the different worlds that make up our peninsula meet in quiet harmony. On the north east corner of Pelham Street and Colbeck Drive is a row of well-kept houses that one might see in any suburban setting in the county. West along River Road a short distance, an old silo stands as a monument to what was once a thriving homestead. Its walls are cracked and broken by vandals and the elements, yet it seems indestructible as it keeps its solitary watch. Further down a farmer unloads a hay wagon, while cattle crowd the fence on the other side of the road in anticipation. To the north on Pelham Street the road becomes gravel and passes more farms and fields, while to the south the Welland River flows by as it has done since prehistory.

Standing on the bank of the river and looking across Riverside Drive a sense of history seems to rise up to meet you. When the water levels are down a little and one looks very carefully one can see, what seem to be, dark spectres rising from the river. There appears to be five of them and with heads just above the water they whisper secrets of a by-gone era. Ghosts? In a way they are ghosts for they are the pilings for Brown’s Bridge for which a small community that thrived before the City of Welland existed was named.

The bridge was built by Lieutenant John Brown who was a veteran of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham and who settled in New Jersey in 1770 with his Scottish wife. During the American Revolution he moved north and lived first at Niagara-on-the-Lake and later settled on a grant of land on the Welland River. He immediately set about building a bridge across the Welland River which bore his name. It was constructed of wood with eight pilings and a deck of planking.

John Brown died of smallpox in 1797 and was buried in the family burying ground on his farm.

During the war of 1812 orders were given to burn the bridges over the Welland to slow the enemy. Misener’s Bridge to the east was torched but for some reason Brown’s Bridge was spared.

A bustling community grew up around the bridge on the north side. There was the Union Section Number Two School which doubled as a meeting house on the Thorold side of the town line.

Brown’s Bridge almost figured in the plans for the first Welland Canal. In 1823 Mr. Hirman Tibbet surveyed several routes one of which he reported: “Commenced at Chippawa on the 6th Inst. 10 miles from its mouth as stated by me, on Mr. John Brown’s farm, Township of Thorold, explored two routes from thence to the headwaters of the 12 Mile Creek.”

In 1824 the first library in the area, called the Welland Library Company, was set up at the school at Brown’s Bridge. Some of the books available were Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, Paley’s Philosophy and Washington’s Official Letters.

The first anniversary meeting of the board was held at the school house on November 26th 1825. Among the shareholders present was Mr. Alexander Brown, son of John Brown. At that meeting the constitution was discussed and it might be of some interest to see how libraries of the day operated. The bylaws concerning the borrowing of books were as follows: Books were borrowed for one month except in the case of someone living five miles from the library or greater. They could keep the book an extra week. The fine for overdue books was 7 ½ pence. Other fines were levied as follows:

1) For folding down a leaf-3.3/4 pence

2) For every spot of grease-3 ¾ pence

3) For every torn leaf -3 ¾ pence

4) Any person allowing a library book to be taken out of his house paid a fine of five shillings.

In 1858 this library was amalgamated with the Mechanics Institute in Merrittsville.

Brown’s Bridge continued to serve the Village of Welland until 1868 when, badly in need of extensive repairs, it was dismantled leaving the pilings to wait for another bridge that never came.

Go down to the foot of Pelham Street some late summer evening when it’s quiet. Sit on the bank of the river and listen to the whisper of the pilings as they tell their tales of by-gone days.

Oh, and don’t be surprised if you hear the clomp of horses hooves and the clatter of wagon wheels on the plank decking of the Brown’s Bridge.

Subscribe..

Subscribe..

A tombstone dated 1840 and bearing the inscription of Elizabeth Ann Spence, wife of Henry Spence, was unearthed by Gerald Parker yesterday as he was tearing down a garage to construct a parking lot for an apartment house he owns at 102 Maple St. Parker considers the stone a rare find, but wonders why it was located on his property since he has no knowledge that a cemetery was ever located there. The stone identifies Elizabeth as the daughter of John and Lydia Barker and says she died Oct. 13, 1840. Parker said he intends to preserve the stone and perhaps donate it to the Welland Historical Society.

A tombstone dated 1840 and bearing the inscription of Elizabeth Ann Spence, wife of Henry Spence, was unearthed by Gerald Parker yesterday as he was tearing down a garage to construct a parking lot for an apartment house he owns at 102 Maple St. Parker considers the stone a rare find, but wonders why it was located on his property since he has no knowledge that a cemetery was ever located there. The stone identifies Elizabeth as the daughter of John and Lydia Barker and says she died Oct. 13, 1840. Parker said he intends to preserve the stone and perhaps donate it to the Welland Historical Society.