Results for ‘Historical MUSINGS’

By Robert J. Foley

[Regional Shopping News, 11 April 1990]

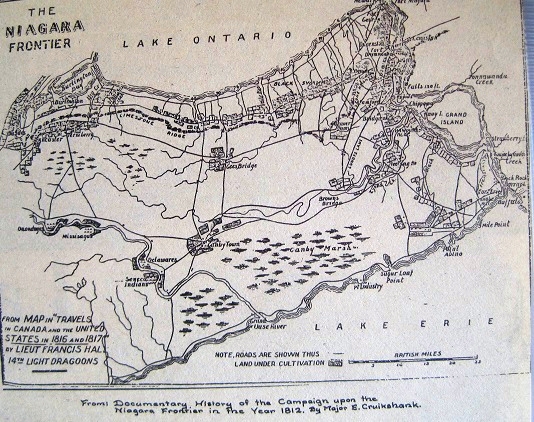

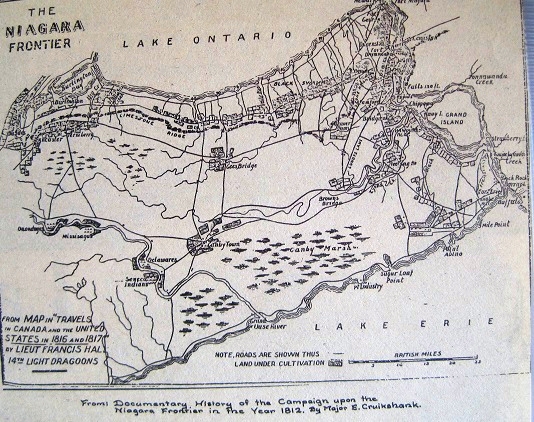

From Map in “Travels in Canada and the United States in 1816and 1817” by Lieut. Francis Hall 14th Light Dragoons.

MAP

At the foot of South Pelham Street the different worlds that make up our peninsula meet in quiet harmony. On the north east corner of Pelham Street and Colbeck Drive is a row of well-kept houses that one might see in any suburban setting in the county. West along River Road a short distance, an old silo stands as a monument to what was once a thriving homestead. Its walls are cracked and broken by vandals and the elements, yet it seems indestructible as it keeps its solitary watch. Further down a farmer unloads a hay wagon, while cattle crowd the fence on the other side of the road in anticipation. To the north on Pelham Street the road becomes gravel and passes more farms and fields, while to the south the Welland River flows by as it has done since prehistory.

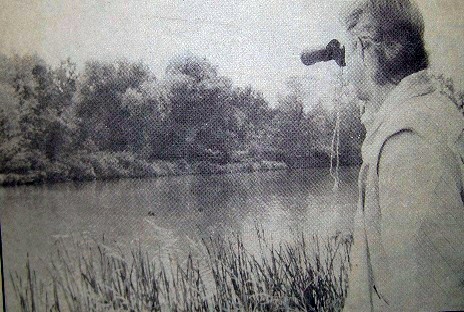

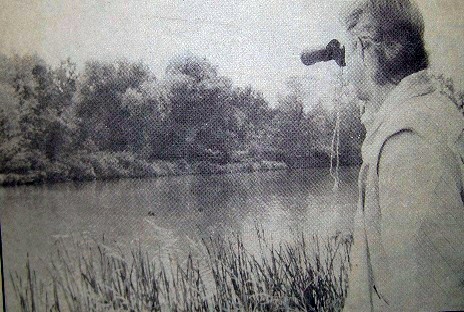

Standing on the bank of the river and looking across Riverside Drive a sense of history seems to rise up to meet you. When the water levels are down a little and one looks very carefully one can see, what seem to be, dark spectres rising from the river. There appears to be five of them and with heads just above the water they whisper secrets of a by-gone era. Ghosts? In a way they are ghosts for they are the pilings for Brown’s Bridge for which a small community that thrived before the City of Welland existed was named.

The bridge was built by Lieutenant John Brown who was a veteran of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham and who settled in New Jersey in 1770 with his Scottish wife. During the American Revolution he moved north and lived first at Niagara-on-the-Lake and later settled on a grant of land on the Welland River. He immediately set about building a bridge across the Welland River which bore his name. It was constructed of wood with eight pilings and a deck of planking.

John Brown died of smallpox in 1797 and was buried in the family burying ground on his farm.

During the war of 1812 orders were given to burn the bridges over the Welland to slow the enemy. Misener’s Bridge to the east was torched but for some reason Brown’s Bridge was spared.

A bustling community grew up around the bridge on the north side. There was the Union Section Number Two School which doubled as a meeting house on the Thorold side of the town line.

Brown’s Bridge almost figured in the plans for the first Welland Canal. In 1823 Mr. Hirman Tibbet surveyed several routes one of which he reported: “Commenced at Chippawa on the 6th Inst. 10 miles from its mouth as stated by me, on Mr. John Brown’s farm, Township of Thorold, explored two routes from thence to the headwaters of the 12 Mile Creek.”

In 1824 the first library in the area, called the Welland Library Company, was set up at the school at Brown’s Bridge. Some of the books available were Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, Paley’s Philosophy and Washington’s Official Letters.

The first anniversary meeting of the board was held at the school house on November 26th 1825. Among the shareholders present was Mr. Alexander Brown, son of John Brown. At that meeting the constitution was discussed and it might be of some interest to see how libraries of the day operated. The bylaws concerning the borrowing of books were as follows: Books were borrowed for one month except in the case of someone living five miles from the library or greater. They could keep the book an extra week. The fine for overdue books was 7 ½ pence. Other fines were levied as follows:

1) For folding down a leaf-3.3/4 pence

2) For every spot of grease-3 ¾ pence

3) For every torn leaf -3 ¾ pence

4) Any person allowing a library book to be taken out of his house paid a fine of five shillings.

In 1858 this library was amalgamated with the Mechanics Institute in Merrittsville.

Brown’s Bridge continued to serve the Village of Welland until 1868 when, badly in need of extensive repairs, it was dismantled leaving the pilings to wait for another bridge that never came.

Go down to the foot of Pelham Street some late summer evening when it’s quiet. Sit on the bank of the river and listen to the whisper of the pilings as they tell their tales of by-gone days.

Oh, and don’t be surprised if you hear the clomp of horses hooves and the clatter of wagon wheels on the plank decking of the Brown’s Bridge.

By Debra Ann Yeo

[St. Catharines Standard, 1992]

Staff Photograph by Mark Conley

Staff Photograph by Mark Conley

They had no obligation to fight in the War of 1812.

Most were former slaves, and few owned land-the criterion for compulsory military service.

Some of their race were still enslaved in Niagara despite a clause in the Upper Canada Act that legislated partial emancipation.

They were: ”Robert Runchey’s corps of colored men ”believed to be the first black unit in Canadian military history.

Only 25 to 50 men strong, they fought at the battles of Queenston Heights and Stoney Creek and against the American siege of Fort George in 1812-1813.

Their contributions to the history of Niagara and Ontario are to be honored with a historical plaque.

The proposed location is Regional Road 81 ( Old Highway 8 ) more than a kilometre east of Jordan-where Runchey’s home, inn and stage-coach stop once stood.

Paul Litt, a historical consultant with the Ontario Heritage Foundation, said Runchey’s men were the only all-Black corps to fight in the War of 1812.

“It shows there was a distinct black community in that area of Ontario at that time, much easier than most people thought. “

“They had enough interest in the British cause to organize to help them in the war,” said Litt.

Jon Jouppien, a member of the committee that proposed the plaque in 1987, said the volunteer soldiers’ contribution to history “sort of fell through the floorboards of time.”

“You would never know they existed,” agreed Al Holden, chairman of the Niagara Heritage Commemorative Committee and an unpublished author of Niagara military history.

Yet, Holden said, the soldiers served “with distinction” at Queenston Heights, part of the first advance against the Americans.

It was Richard Pierpoint, a former slave who was one of the first few black landholders in Niagara and one of the first settlers in what is now St. Catharines, who organized the company.

Since there were no black army officers, Pierpoint, a private, wasn’t allowed to lead the corps. It was Runchey, a white man and member of the first Lincoln Militia, who was given command.

Even though he led the company less than a year, they were known throughout the war as “Runchey’s company of colored men.”

Most had escaped slavery in the U.S. Some had served with Butler’s Rangers during the American Revolution.

Most resided in Niagara, although some came from York (Toronto) where they had joined the militia.

Holden tells a tale of one slave named Jack who fled his Grimsby masters to join the company. He was turned away when his owner came to claim him.

Despite the Upper Canada Act, slavery was not officially abolished in Canada until 1834 when it was banned throughout the British Empire.

Runchey’s men were headquartered in Niagara-on-the Lake during the war but segregated from the white troops.

By 1814-the year they finally got uniforms of black gaiters, green jackets with yellow facings and felt caps with plumes-they had become artificers, excavating earthworks and doing other engineering jobs around Fort George.

Records obtained by Holden from the national archives show 14 of Runchey’s men were dead by 1820, at least 10 were still in Niagara, seven deserted during the war and at least two died in battle.

Volunteers who had kept their posts and lived were granted land for their service.

By 1819, Runchey was also dead. His house stood until the early 1970s’ when it was demolished after a fire.

Although the committee hoped to erect the plaque to coincide with Jordan’s Pioneer Day, Litt said, it’s too late to make the Oct. 17 date.

A second provincial plaque honoring Harriet Tubman will be erected in St. Catharines in February 1993, which is black history month.

Tubman was an escaped American slave who lived in St. Catharines from 1851 to 1858, according to the St. Catharines Museum.

Nicknamed Moses, she made many dangerous trips back to the U.S., guiding a least 300 slaves to freedom in Canada along the famous Underground Railroad.

The home she rented on North Street, which is no longer standing, was used as a boarding house for the escaped slaves.

Pilings still visible in Welland River, as Historian seeks complete story

17 March 1943-25 July 2016

[Guardian Express]

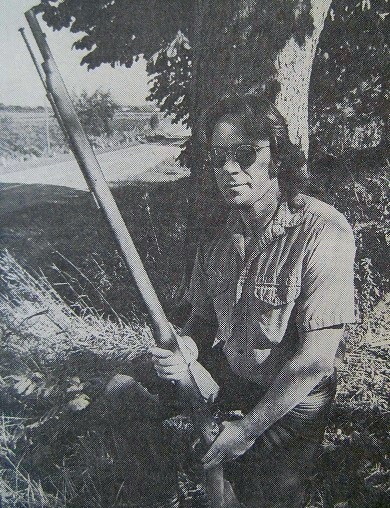

A lot of water has passed over the bridge since Tony Whelan was a kid. Yes-over the bridge. The Brown Bridge.

Growing up on River Road, Whelan remembers being told to stay clear of the old bridge pilings in the Welland River near Colbeck Drive, whenever he set out in his row boat.

Growing up on River Road, Whelan remembers being told to stay clear of the old bridge pilings in the Welland River near Colbeck Drive, whenever he set out in his row boat.

He stayed clear, but remained intrigued.

Whelan believes the bridge is an important part of local history that has been overlooked. And with the only people who may remember it growing older all the time. Whelan said he he’s afraid the Brown Bridge chapter of the city’s history will be lost forever.

As a historian, Whelan isn’t happy about progress’s tendency to sever its ties with the past.

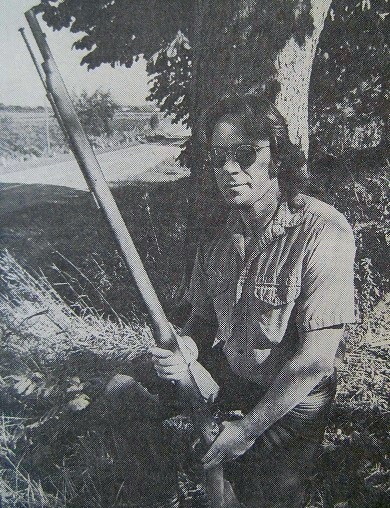

Although by trade he’s a professional entertainer, a deep interest in genealogy and history consumes most of the rest of his time. Whelan lives in the same house-even sleeps in the same bedroom-he was born in. While he’s reluctant to disclose just how many years ago that was, the fact the youthful-looking Whelan has two young grandchildren gives a clue to his approximate age.

“When you do find something,” Whelan says of historical research, “oh, the feeling, the rewards. You think you just won the lotter.

CHAIRMAN

Now second chairman of the Niagara branch of the genealogical Society of Ontario, Whelan says he became interested in family and local history “because it was there.”

“It was just something of interest. And as it gets under y our skin, that’s it-you’ve had it” he says, a bright white smile breaking on his tanned face.

A self-confessed admirer of the off-centre facts in life, Whelan says he’s looking for the “horse thief” in his family tree. So far, Benedict Arnold is the only high profile black-mark in Whelan’s mother’s lineage.

Whelan, himself, ran away with the circus as a young teenager. He says he can’t help wondering what future generations of Whelans will think of him.

In one corner of Whelan’s dining room, Reuben, a yellow cockatiel, oversees the interview perched atop the outside of his cage. Behind an antique dining set, a bay window opens the room to a view of a lush rear yard. At the yard’s foot flows the Welland River.

The mysterious Brown Bridge pilings poke out of the water about a mile-and-a-half downstream.

Whelan believes the bridge was built by John brown, who died in 1797. Recently Whelan was told by an elderly area resident that the bridge collapsed under the weight of ice, in 1926.

The 83-year old gentleman who told Whelan that also gave him a detailed description of what the bridge looked like, and Whelan was able to make a sketch of it.

So far, though, the ice collapse has gone uncorroborated. *There are many blank areas in the 1926 newspaper that might have corroborated this.

Whelan says that during the War of 1812, Misener’s Bridge, which ran parallel to Brown’s Bridge further east on the river was burned. After breaking away from the control of the American army in 1813, the Canadians (then United Empire Loyalists) apparently torched the bridge to protect themselves from anther invasion.

Whelan believes that William Lyon MacKenzie, in his 1837 escape to the United States, crossed the Welland River over Brown’s Bridge. A newspaper publisher, expelled member of the Ontario legislature, and open advocate of an independent Canadian government. MacKenzie later returned to Canada on an amnesty grant for rebels.

COMMUNITY

In researching the area near the Brown’s Bridge, Whelan discovered it was a bustling, self-contained community at one time. Welland’s first library was there, doubling as a public meeting house. The library wasn’t moved to downtown Welland until 1858. There was a schoolhouse near the bridge site, on the Thorold side of Townline Road.

“This bridge has a lot of historical value,” says Whelan wrinkling his brow. “If we don’t get the information on it now…”

“I’m searching out anybody who definitely know about the area and particularly about its bridge,” he says. “I need help from this area’s senior citizens.”

Whelan maintains he will make sure any information he gets will be properly recorded, so this will be available to future generations.

“If you don’t know where you’ve been, how do you know where you’re going?” he asks.

by Sheila Hird

[Welland Tribune]

In 1812 residents of Niagara were busy clearing land and settling into their new homesteads. The last thing on their mind was war.

Bur James Madison, the president of the States, quickly changed that when, to retaliate against Britain for blocking the States, he declared war on Canada on June 18, 1812.

The Americans underestimated Canada’s loyalty to Britain and thought the war would be a short one. General Widgery declared he would conquer Upper Canada in six weeks. Mr. Calhoun thought he was being ridiculous and that it would take no longer than a month. Henry Clay firmly stated he would never settle for a peace treaty that did not cede Canada to the States.

Much to everybody’s surprise the war dragged on for two and a half years and did not conclude as the Americans expected.

The war was mainly fought in battlefields in the Niagara peninsula, Queenston, Fort George, Stoney Creek, Beaver Dams and Lundy’s Lane are a few names among many.

QUEENSTON

The men from the Niagara region fought in the first regiment of the Lincoln Militia under the command of Captain James Servos. Most of these men were farmers who had fled from the States as United Empire Loyalists.

When General Brock arrived in the peninsula he positioned the majority of troops in the town of Queenston and the remaining troops on the summit of Queenston Heights.

The townspeople prepared for an American attack by burying their valuables or by taking them to friends who did not live in the battle zone.

In the early morning of October 13, 1812, the American forces gathered at Lewiston. The sound of cannon fire woke General Brock from his sleep. Captain john Ball, who had kept watch throughout the night, poured a volley on the approaching American boats. In return the enemy poured a heavy shot from Fort Niagara that set many of the houses and buildings on fire.

Although Brock and his aide-de-camp, McDonell, were quickly on the scene, the enemy beat them to the summit of the heights.

Brock, determined to take the heights, charged the enemy’s troop of 4,000 men with a troop times smaller. After uttering his last order “Push on York Volunteers” Brock was hit in the chest. Seconds later McDonell was also struck. Brock died that same day and McDonell the next.

Despite the causalities on the British side, the charge had succeeded in throwing the American troops into a state of confusion. When General Sheaffe arrived with the reinforcement troops the battle was quickly concluded. The Americans raised the white flag while more than 900 of their men were taken prisoner and sent to Queenston.

FORT GEORGE

The defeat of Queenston did not end the American offensive.

On April 27, 1813, General Dearbon and his troops settled into the undefended town of York. After setting fire to the government buildings, many private buildings, the library and the shipyard, the Americans evacuated the town

On May 27, the American troops, numbering about 6,000, arrived at Crook’s farm hidden from the British by a blanket of fog over the lake.

They opened fire on the British troops who numbered less than 1,500. General Vincent repulsed the enemy three times as they attempted to land at Fort George but he soon ran short of men and ammunition.

After spiking all the guns of the fort and destroying all the military paper, General Vincent ordered a retreat. After evacuating the fort, the troops took the River Road to Queenston and then marched on to Burlington Heights, leaving the Americans in charge of the peninsula.

STONEY CREEK

A few days after the British troops arrived at Burlington Heights, the Americans, under the command of Generals Winder and Chandler, set out in pursue them.

On June 6, the American troops stopped at Stoney Creek to spend the night. Vincent, eager to learn the strength of these troops, sent several of his soldiers dressed as civilians to sell butter and cheese to the enemy.

Vincent and his aides, Harvey and Murray, resolved that the only way to take such a large force was to attack by night.

Colonel Harvey with a small force, attacked the American camp before dawn. They were followed by several Indian troops and the rest of the militia numbering less than 800 men.

Although the Americans had almost four times as many men, they were soundly defeated. Generals Winder and Chandler were taken prisoner. The guns and supplies were confiscated and the whole camp gutted. The British were surprised that it took the Americans four days to reach Stoney Creek but only one day to return. The British troops were now able to advance to within four miles of Newark.

BEAVERDAMS

As the British retreated to Burlington Heights before the Stoney Creek battle, Vincent ordered all arms and ammunition be stored in John DeCew’s farm (near Beaverdams) in Thorold township.

Lieutenant Fitzgibbon and his troop of Green Tigers known as “Fitzgibbon’s Green Uns” guarded this depot. It was not long before the Americans received wind of this arms cache and busied themselves planning for a surprise attack.

The events that followed tell the famous story of Laura Secord.

The American soldiers preparing for the attack were billeting at the home of Peter and Laura Secord. One evening Laura overheard plans for an attack on the DeCew farm and made up her mind to embark on a twenty mile journey to warn Fitzgibbon.

One tale tells how Laura set out the following morning with a milk bucket over her arm and a cow by her side. Although this story may have some truth in it, it is generally believed that Laura used the excuse of her ailing brother to slip past the guards.

Fearing she might meet General Boestler’s men on the main road, Laura travelled by the Swamp Road. While hurrying along the road to avoid meeting the wolves and rattlesnakes that inhabited the area, Laura lost a shoe.

The second shoe was lost as Laura made a dangerous crossing of the Twelve Mile River. The flooding river had swept away the bridge and Laura was forced to cross the raging waters by crawling along the trunk of a fallen tree. Despite all these difficulties Laura arrived at the DeCew farm and gave her message to Fitzgibbon.

Preparations for an attack were begun immediately. The supplies were sunk in the DeCew pond and scouts were sent to find the enemy. A party of Indians under the command of Ducharme were then sent out to ambush the Americans.

As Boestler’s men marched along the Mountain Road past the farmhouses of the Browns, the Hanslers, the Metlers and the Hoovers, the Indians lay in the thickets waiting. They waited until the troops were past them before they opened fire on the rear and on the flanks.

At the point Fitzgibbon and his men appeared to reinforce the Indians. After a three hour battle the Americans surrendered. Thanks to Laura Secord the British won the day and the Battle of Beaverdams proved to be the turning point in the war.

NEWARK

As winter drew n near, the Americans occupying Newark realized they had to retreat before the ice and snow closed up the river.

On October 14, 1813, two companies of soldiers left Fort George at 1 p.m., armed with torches and lanterns.

They gave the 400 residents of Newark one hour’s warning before setting the town to flames. It took the soldiers less than half an hour to set the whole town ablaze. By the time the British arrived on the scene, the enemy had escaped and the only building left standing was Butler’s Barracks.

After the British retaliated, neither the Americans nor the British were eager to continue the war. Lengthily negotiations resulted n in a peace settlement in which both sides accepted the status quo. The treaty was signed in Ghent on Dec. 24, 1814.

Sheila Hurd

[Evening Tribune]

Ma Bell came to town in 1885.

Twenty-seven Wellanders signed up for the new service, which enabled them to make long distance calls to Thorold, Port Colborne, Niagara Falls, St. Catharines and even to Buffalo.

During these early days of the telephone, directories only listed names, not numbers. It was not until 1889 that directories also included telephone numbers.

A switchboard was installed in Clayton Page’s Main Street grocery store and Page became the first Bell agent in Welland.

J.S. O’Neill was in charge of the switchboard and Miss Toddy Tucker was the first switchboard operator. Female operators were preferred to males because they were more polite.

The Welland switchboard changed locations with each new agent. After two years in the general store, the switchboard was moved to an insurance office and later to a book and stationary store. The switchboard was opened for calls only as long or the store which housed it was open for business.

A turn of the telephone crank connected the caller to the operator. The speed of the telephone service in Page’s general store depended on how busy Page and his clerks were with customers.

In the early years, the idea of the telephone did not catch on very quickly in Welland because the railway interfered with the telephone connection.

By 1901, 36 Wellanders had telephones. In 1903 a second switchboard was installed and in 1906 24-hour service was introduced. By 1910 the number of subscribers had jumped to 488.

A new bell building opened on Division Street to accommodate the growing company. Dial service was introduced in 1942 and direct distance dialing in 1968.

[Welland Tribune, July 1984]

By Sheila Hird

A study room of the Niagara-on-the-lake library was once used to imprison criminals.

The room served as the solitary confinement cell of the first jail in the Niagara Peninsula.

Early document show that the most common crimes committed by the first settlers were assault and battery, uttering profanities in public, larceny, and participating in riots.

Punishments included banishment, the pillory, whipping and hard labor. Punishment for keeping a disorderly house was three months in jail and one and half hours in the pillory. For stealing goods from a store, the penalty was two months in jail and two public whippings.

Many of the early punishments and laws were very unusual. For example, in 1819, Rev. Henry Ryan, the Methodist Superintendent for Upper Canada, was sentenced to 15 years banishment for marrying. Early records refer to a Stump law, which stated that any person arrested for drunkenness had to remove a certain number of stumps from public property.

Execution was a common punishment for crimes ranging from horse stealing to murder.

The earliest recorded execution in Niagara’s history was that of Mary Osborne London and Georges Nemiers on August 17, 1801.

This execution was the final stage of a love triangle that began when Barth London left a family and a homestead in Pennsylvania to become one of the first settlers in the Niagara region. He took in a 28-year-old widow as a housekeeper and, after getting the girl pregnant married her.

George Nemiers, a young farmhand, was hired by London and shortly afterwards a love triangle developed between the three inhabitants of the farm.

During one of many fights, Nemiers took a hammer and hit Barth over the head with a blow so hard that the doctor predicted that it would soon lead to Barth’s death.

George and Mary, impatient to get rid of Barth and have the farm to themselves, administered poison to Barth. When his potion proved too weak, they mixed arsenic and opium with Barth’s whiskey. This concoction did the trick and Barth soon died, leaving the farm in Mary’s name.

Unfortunately for Mary and George, the rest of the operation did not go smoothly. Within a week the couple were arrested and, after an eight-hour examination in which each tried to blame the other for Barth’s death, they were both found guilty and sentenced to death.

Niagara-on-the-Lake did not have its own resident hangman, so normally one was sent from Toronto. Early documents show that on the scheduled date of one execution, the hangman had an appointment elsewhere in Upper Canada and Alexander Hamilton had to perform the hangman’s duties for the day. In fear of messing up the execution, Hamilton ordered the construction of a special scaffold that would allow the prisoner to fall twice the usual height.

A prisoner was left hanging for about 25 minutes to ensure that he had met his end while the coffin lay nearby. The earliest executions were held in public and drew large crowds. Merchants also flocked to executions to sell wagonloads of cakes and gingerbread.

Another unusual early legal practice dealt with creditors and debtors. A creditor had the right to throw a debtor in jail until he paid in full the sum he owed. The catch was that the creditor was responsible for the debtor’s upkeep while he was in jail.

Records show that a debtor who had been in jail for many years was greatly relieved when his debtor finally died, until he learned that the creditor had included a clause in his will continuing his upkeep in prison. The executors of the will felt that this was a cold-hearted act, and they delayed the delivery of the upkeep fee so that that debtor was eventually released.

Court Assizes were held only once a year. Those who were arrested immediately after the assizes were concluded for that year had to wait in jail until the following year.

The jail and courthouse were burned to the ground during the Battle of Queenston Heights on October 13, 1812, A new jail and courthouse were erected in 1816.

An advertisement in the St. David Spectator of 1816 asked that stone, timber, brick, shingles and timber be delivered to Niagara between June 1 and July 13, 1816, for the purpose of rebuilding the jail and courthouse.

Two years after the new building was complete the renowned Gourley trail was held.

After being imprisoned for several months for his outspoken criticism of the government, Robert Gourley, known as the Banished Briton,-was tried and fined for sedition. This punishment was not enough to stop Gourley’s outspoken criticism and he soon found himself in exile for 15 years. Word reached Niagara that Gourley’s treatment was so harsh that he had temporarily lost his sanity.

Gourley was not the only one who suffered during this incident. The printer of the Niagara Spectator printed a letter of Gourley’s without the publisher’s knowledge. As a result, the printer was tried for sedition, sentenced to stand in the pillory and fined 50 pounds.

Thirty years after the building of the new jail and courthouse, controversy still flared over the site of the buildings. A group of the town’s inhabitants complained that not only were the jail and courthouse far from the town’s centre, they had been built in a swamp.

In 1847, the debate was silenced when a new courthouse and jail were erected on the main street. The building was used for this purpose for only 15 years. In 1862, St. Catharines became the county seat and a new jail and courthouse were erected on Niagara Street.

The mid-19th century witnessed the building of yet another jail and courthouse. Built in Welland

in 1855, when the town gained county seat status, the new jail housed 45 males and nine females and was enclosed by a 300-foot long, 21-foot high and two–foot thick wall.

The first execution in the Welland jail, and the first execution outside of the Niagara-on-the-Lake, took place on May 31, 1859.

On this date John Henry Byers met his end. Special stands and roof-top seating accommodated the crowd of about 4,500 who gathered at the jail to witness the execution.

After Tomas Arthur Laplante was hanged on January 17, 1958, the Welland jail became known as the place of the last execution in the Niagara Peninsula.

While the Welland and the St. Catharines jails were filled with prisoners, the old jail at Niagara-on-the-Lake was filled with orphans.

The jail and the courthouse lay vacant until Miss Maria Rye’s Western Home for Girls was established in 1869 to train young girls as domestics. Minor renovations were made including the conversion of the courthouse into a dormitory.

After Rye’s death, the buildings remained vacant until the First World War, when they were used by Polish troops as a hospital and barracks. After 1917 the jail and courthouse were again empty until purchased by Charles Currie who tore the buildings down using the materials in the construction of other buildings.

The Rye Cottage, located at the corner of King and Cottage Streets, still stands today as reminder of the colorful history of Niagara-on-the-Lake’s jail and courthouse.

By Robert J. Foley

[Regional Shopping News, 2 May 1990]

Humberstone Township might have remained a rural community but for the vision of William Hamilton Merritt. Merritt’s dream of a canal to connect Lake Erie with Lake Ontario was to change the destiny of Humberstone forever. Although the first canal initially made a left turn at Port Robinson to follow the Chippawa to the Niagara River, it became evident when the canal opened that it would have to be pushed through to Lake Erie if it was to be a viable proposition.

Work began on the extension in 1831 with Gravelly Bay (Port Colborne) chosen as the southern terminus of the canal. Humberstone Township was on the map and its future was assured. All proceeded without undue delays until 1832 when a cholera epidemic struck the work force. The lack of good drinking water and the consumption of a great deal of alcohol combined with appalling sanitary conditions played havoc with the health of the men tolling the canal. An excerpt from a letter from Merritt to his wife may give some indication of what was going on. “Tuesday, went through the line with Mr. Lewis, and as no new cases occurred that day, the men generally went back to work.

Slept at Holmes’ Deep Cut, that night Lewis was taken; in the morning (Wednesday) sent to St. Catharines for Drs. Gross and Converse, who was up at Gravelly Bay. Lewis was very much alarmed and I could not leave him until Cross arrived about 2 o’clock. Mr. Fuller had bled him and I gave him two pills of opium. He got better immediately and is now well. Returned to Gravelly Bay that night to quiet the minds of the men respecting Mr. Lewis. We found all who got medical aid were bled recovered. He has hopes of continuing the work, but on reaching Gravelly Bay found Dr. Ellis and Mrs. Boles had taken it. Remained there until 12 o’clock, Thursday, and left for the dam with the determination to let everyone take their own course…stopping the sale of liquor and providing doctors on the spot.

Friday..went to Nelles’ settlement. Saturday returned to Dunnville and have got this far to breakfast, am on my way to St. Catharines where I have not yet been. I thank God that I am in good health and will take every possible care of myself. Should the disease continue I will go over to Mayville next week, if not, will remain until the middle of August.

With my best wishes and prayers for your safety, I remain your affectionate husband, W.H. Merritt.”

One of the many offshoots that sprang up as a result of the canal was the towing industry. In the days before power, sailing ships had to be towed through the canal. Truman Stone, owner of the Humberstone Livery stable, made his living towing ships. Charles and William Carter began towing in 1838 and later converted their operation to steam tugs. Charles’ sons continued in the business and ran three steam tugs, the Escort, Alert and Hector. Pictures and models of these vessels can be seen at the Port Colborne Marine and Historical Museum.

The Baldwin Act of 1849 was passed to allow for local municipal governments and in January 1850 the residents of Humberstone met at Petersburg to appoint a council. It was composed of the following: Christian Sherk, David Steele, Abraham Schooley and Samuel Stoner. On January 21, 1850 the first council meeting held at the home of Owen Fares, elected William Steele as the first Reeve.

In 1854 the southern portion of the peninsula was separated from the rest and Humberstone became part of the new County of Welland. Daniel Near, the Reeve of Humberstone was part of the Provincial County Council which oversaw the birth of the new county.

Some of the minutes of the township council meetings give us a glimpse of the cost of some of the services the council paid for:

1861, Dec. 7th-Paid B. Yokum and Wm. Page $1.00 each for a coffin and burying Robert Smith found drowned in canal at Port Colborne.

1862, Oct. 13th-Council paid A. Boyer $3.00 for a coffin and burying a man found drowned on lakeshore near Shisler’s Point.

1866, May 12th-Moved by Dr. M.F. Haney, seconded by Jacob Benner, that $20.00 be allowed to Cyrenus near and Asa bears for building a bridge between lots 10 and 11 Con. 1 Bridge to have a span of 12 feet and 14 feet wide, supported at each end by a substantial stone wall 3 ½ or 4 feet high and 2 feet thick. The plank to cover the bridge is to be 2 ½ inches thick, spiked down.

The bridge, when done, shall be subject to inspection by Jacob Benner and M.F. Haney. Material required: 7 Cu. Ft. of stone and 420 board feet of plank.

1867, June 24th-Council paid John Liedy $4.50 for 36 loads of stone for road purposes.

Humberstone continued to prosper as our forbearers intended until its annexation by Port Colborne. Although it has disappeared from the road maps of the region and the province, Humberstone Township will continue to influence the history of the Niagara Peninsula for generations to come.

By Robert J. Foley

[Regional Shopping News, 18 April 1990]

He had to be the youngest tug boat captain on the Great Lakes. Eight years old, and here he was easing the steam tug “Yvonne Dupre Jr.” alongside the towering line. He had to get a tow line on her before she went hard aground in this raging gale. He yelled orders confidently to his crew who answered with a smart, “aye aye sir,” as they rushed to do his bidding. The stout little tug pulled her clear in the nick of time to the cheers of the big liner’s crew. The shout of “Come, on, Sean, we’re going for a drink,” broke the spell and our captain rushed off to join his family once again.

Was Sean having a dream? Yes and no! He was the captain of the “Yvonne Dupre Jr.” and he was standing in her wheelhouse giving his commands, however, the wheel house is located on the grounds of the Port Colborne Historical and Marine Museum, at the corner of King and Princess Streets in Port Colborne.

The “Yvonne Dupre Jr.” was built at Sorel, Quebec in 1946 by Marine Industries. When her working days were over, the museum was able to salvage her wheelhouse to enthral the imagination of kids of all ages.

The museum founded in 1974, has developed into a small heritage village with six buildings and the tug wheelhouse on the property.

The museum traces the history of Port Colborne from the first schoolhouse built in 1818 through the canal construction of the early 20th century.

The main museum building is a Georgian revival style home built in 1869 by John Williams. The house was bequeathed to the city by Arabella Williams, the daughter of John and Judith Williams in 1950 and was taken over by the museum at its founding. This building contains items of local historical interest including models of lake steams as well as native artifacts, Erie and Foster Glass Works and many exhibits tied to the Welland Canal.

The anchor near the wheelhouse was salvaged from the wreck of the “Raleigh” in 1975. The “Raleigh” was built in 1876 and sank off Port Colborne in a storm in 1911.

The carriage house, a part of the original estate, is of board and batten construction with hand hewn beams. It is used as a learning and activity centre for school programs.

The log school house, the first in Humberstone Township, was built in 1818 by Pennsylvania Dutch settlers. It was torn down and rebuilt on the museum grounds in 1976.

The log house, the first home of John and Sally Sherk, was moved to the museum property from Humberstone and is furnished to show the lifestyle of the Pennsylvania Dutch Mennonites of the 1850’s.

The blacksmith shop was relocated from the Port Colborne Quarries property in Humberstone Township and reconstructed here in 1984. It represents the blacksmith operation of F.W. Woods & Sons which served the canal trade in the 1880’s.

Finally, after touring the many exhibits, one can retire to Arabella’s Tea Room, a 1915 cottage that had been part of the Williams estate. From June through September tea and hot homemade biscuits are served. *Note: I had the opportunity to have tea at Arabella’s and it was delicious. B.

May 1st is the official opening of the museum for another season. This year the museum has added new exhibits, including “Patters of the Past,” a history of the Graf family of weavers and their products. “Canadian Handweaving Samples” is a traveling exhibit from the Royal Ontario Museum which allows you to examine and touch the exhibits.

The Niagara Peninsula has more history per square metre than anywhere in Canada. It has participated in the growth of this country from the days of the fur trade, through the struggle to retain the right to be Canadians, to the building of the great canal which insured its prosperity.

There are museums in almost every community across the Peninsula. Find out where they are and visit them. In this time of controversy and turmoil it is important that we get in touch with the roots of our country and gain an appreciation for the sacrifices that our forbearers made in making Canada what it is today.

The Port Colborne Historical and Marine Museum is located at 280 King Street. 1990-Admsiion is free, and the museum, which is wheelchair accessible, is open form 12 noon to 5 p.m. daily.

Bring the family. The “Yvonne Dupre Jr.” is always looking for a good captain.

By Robert J. Foley

[Date Unknown]

Visitors to Niagara Falls, who happen, by chance or design, to drive out Lundy’s Lane along Highway 20 and cross the canal bridge at Allanburg are in for a treat. Astride the hills which dominate the landscape is the village of Fonthill, sitting like a crown on the brow of the Peninsula. Fonthill forms the hub of what is now the town of Pelham.

The first settlers in the area were refugees from the American Colonies who began arriving as the revolutionary war was in full swing. Major David Secord, brother-in-law of the famous Laura Secord, settled on three hundred acres in the area around 1781. By 1783 there were 46 families in the township which was named Pelham by the Lieutenant-Governor, John Graves Simcoe. David Secord became the Justice of the Peace and a small community began to grow where Fonthill now stands.

Among the early arrivals was one George Hansler who settle down with his wife and daughter in 1782. He became a benefactor to the community when he donated the land for a school in 1821, which was appropriately named Hansler school. Nichols Oille settled in 1783 and built the first brick house in the township with clay from his own land.

The War of 1812, which devastated much of the Peninsula bypassed Pelham as far as material destruction went, however many of her sons served in the militia and so action in many of the battles fought in the peninsula. Despite this fact, Pelham almost became a military base. The Duke of Wellington visited the peninsula in 1825 and upon seeing the dominant position that the town held from the ridge, which now boasts the Lookout Point Golf Course, he proposed to build a fort there. It even got to the design stage before the plan was abandoned.

Pelham did not remain immune from the fortunes of war however. During the rebellion of 1837, a number of locals sided with William Lyon MacKenzie and in that year 38 men and two women were rounded up and charged with treason. The group was sentenced to death by hanging but the sentences were commuted to being transported to a penal colony in Tasmania for life. One Samuel Chandler, however, managed to escape and returned home in 1841, he packed up his family and moved south never to be heard of again.

In 1871 Pelham boasted a population of 776 with three grist mills, six saw mills and all the other amenities that made up a prosperous community in the early part of the 19th century. Many of the peninsula’s settlements underwent many name changes before they received the ones we know today and this one was no exception. It was first known as Riceville after one of its early justices of the peace. It was called Osbournes’s Corners, for Osbournes’s Inn for a short time after 1842 but then was again changed, this time to Temperanceville, probably to the chagrin of Mr. Osbourne the inn keeper. In 1850 it finally received a proper name and became Fonthill after Fonthill Abbey in England.

The mid-19th century were momentous times for Pelham. In 1851 Fonthill, because it held the local registry office was in the running for the new Welland County seat along with Port Robinson, Cook’s Mills and Merrittsville. The competition was hot and heavy and in 1854 Merrittsville (Welland) won out. Looking at the region today we might think Welland was the obvious choice, however in 1850 the population of Welland was 750, while Pelham could muster a count of 2,253 souls.

Today Pelham, containing some of the most beautiful landscape in the peninsula, consists of the villages of Ridgeville, North Pelham, Effingham, Fenwick and the surrounding agricultural lands.

It is, indeed, the jewel in the crown.

First recorded meeting in 1845

By Joop Gerritsma, Tribune Reporter

[Welland Tribune, 25 May 1979]

Glad Tidings Church of God will celebrate its 75th anniversary the weekend of May 22-27 and the week of May 30 to June3 with a series of special services, during which former pastors of the church will speak.

But the work of the Church of God in Canada actually began before Confederation, the current pastor of the church, John Hearp, said.

The first recorded meeting took place in Bouk’s School House in 1845 in Fonthill. Thirteen years later in 1858, the congregation built a church just east of the Village of Fonthill and church gatherings were held in this building until 1890, until it was sold.

In 1891 the congregation moved into Fonthill itself, when meetings were held in Dalton’s Hall, a building now occupied by Howey’s Jewelry Store on Pelham Street.

It was not until 1904 that the congregation saw a need for a full time pastor and F.L. Austin was called to serve both the Fonthill church and the Church of God located in Niagara Falls, N.Y.

Records show there were 25 members of the church in Fenwick, who, however, did not formally affiliate with the Fonthill church until 1908.

PROPERTY BOUGHT

In the fall of 1908 construction was started on a new church building in the centre of Fonthill. It was dedicated Feb. 14, 1909. The cost of building the church was $3,500, a phenomenal sum in those days, but the debt was paid in 1910. The building became known as “The Church in the Heart of the Village,” located as it was on Highway 20 in the core area. The building is now used by Frontier Sport and Marine.

During the years that followed, various departments were incorporated into the church. The first choir director was appointed in 1915. A junior group was started in 1923.

In 1931 Clyde Randall became minister of the Fonthill church. He was to remain in this position until 1948, when he retired. Recently, however, he was the editor of the Restitution Herald, the international publication of the Church of God General Conference, with headquarters in Oregon, Ill.

NEW EXPANSION

The next expansion for the church was the purchase of a permanent parsonage on Church Street in 1942 at a price of $4,500. A major expansion followed in 1948 when the congregation at Niagara Falls, N.Y. transferred its membership to the Fonthill church. However, records are silent about the number of people joining the Fonthill church on that occasion.

In the same year the Dorcas ladies society was formed by church members to serve as a community organizations.

Some much added additions to the church building were completed in 1951 and 1952, but opportunities for real expansion and an increase in parking space were non-existent and the congregation started looking for another location. This was found and purchased in 1961, when three-and-a-half acres were acquired on Hillcrest Road, later renamed Pancake Lane. The first sod was turned in March of 1968.

In 1961 Rev. Edward Goit took over the congregation, but he left the following year and was succeeded by Pastor Emory Macy, who was the church’s pastor during the years it struggled to get its new building on Pancake Lane. Mr. Macy left in 1971.

Also during Mr. Macy’s tenure, the Fonthill Church of God had accepted an invitation from the former Ohio Conference of the Church of God to join them and they formed the Church of God Northeast Conference.

In the same period of time the Mary Marthas women’s group was formed. The funds raised by this group during the years have been donated to the church for its many projects.

NEW BUILDING

The first service in the new church building was held Sept. 1, 1968, and members staged a parade from the former church to the new one that day. At this time the new building was, however, only partially completed. The present church was dedicated the following Nov.17 and in 1973 the debt on the new building was paid for. This was marked by a ceremonial bond-burning May 27.

Growth continued and junior church services were started in 1975 as part of the organizations of a nursery to better minister to the entire family. In the same year a memorial fund was established, which has resulted in many gifts of lasting duration for the Lord’s work, Mr. Hearp said.

In 1976, a women’s fellowship group was formed and a new public address system was installed in the church, followed by the purchase of a new digital computer organ in the fall of 1977. It was dedicated at a special service Dec. 11.

Construction of a new parsonage adjacent to the church was started April 23 and was completed later in the summer of that year.

This year saw the introduction by the Glad Tidings Church of God of a new busing program, offering transportation to those who were unable to get to the church by themselves.

Mr. Hearp said it was impossible to name all the people who labored in carrying on the Lord’s work through the channel of the Glad Tidings Church.

“We look to the past with appreciation,” Mr. Hearp said. “The present is bright with opportunities to service to God and others,” among them, the approximately 100 active members and about 60 others who are inactive.

Subscribe..

Subscribe..

Growing up on River Road, Whelan remembers being told to stay clear of the old bridge pilings in the Welland River near Colbeck Drive, whenever he set out in his row boat.

Growing up on River Road, Whelan remembers being told to stay clear of the old bridge pilings in the Welland River near Colbeck Drive, whenever he set out in his row boat.