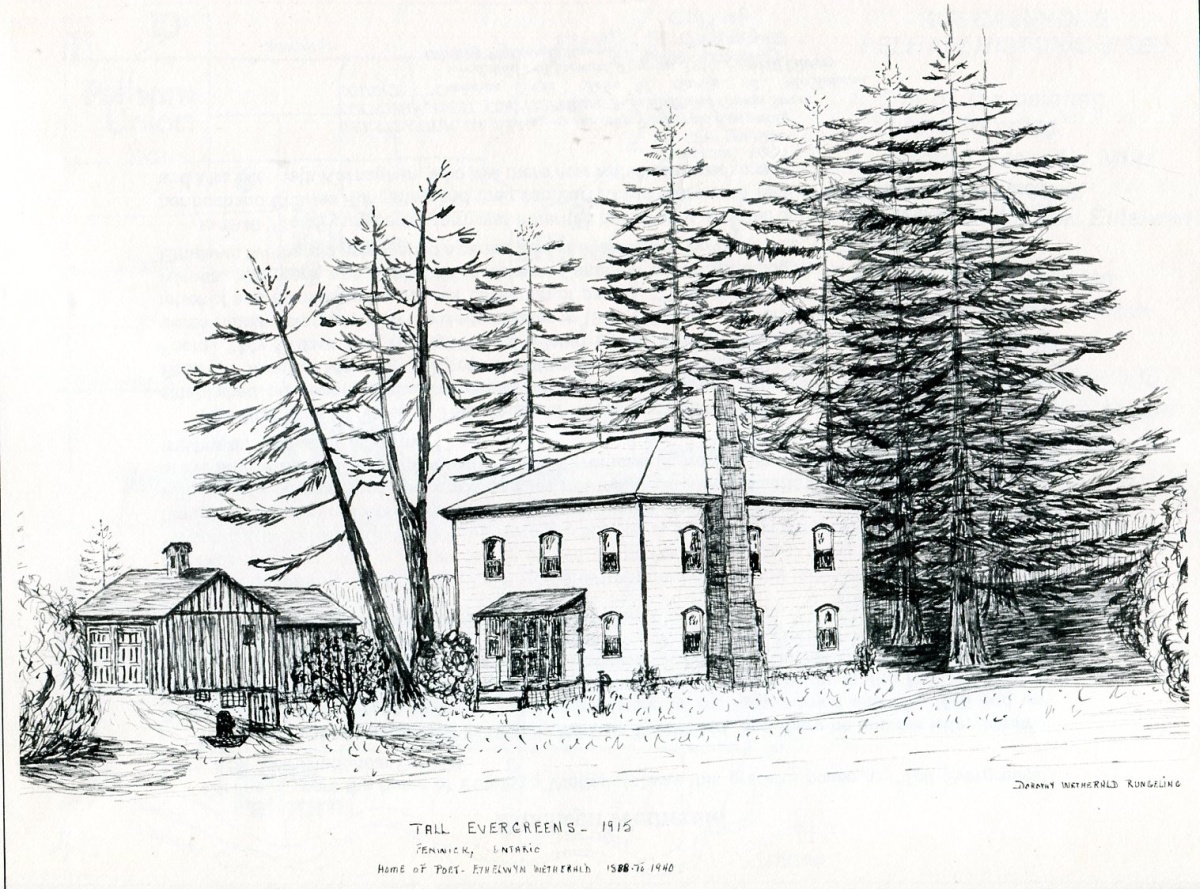

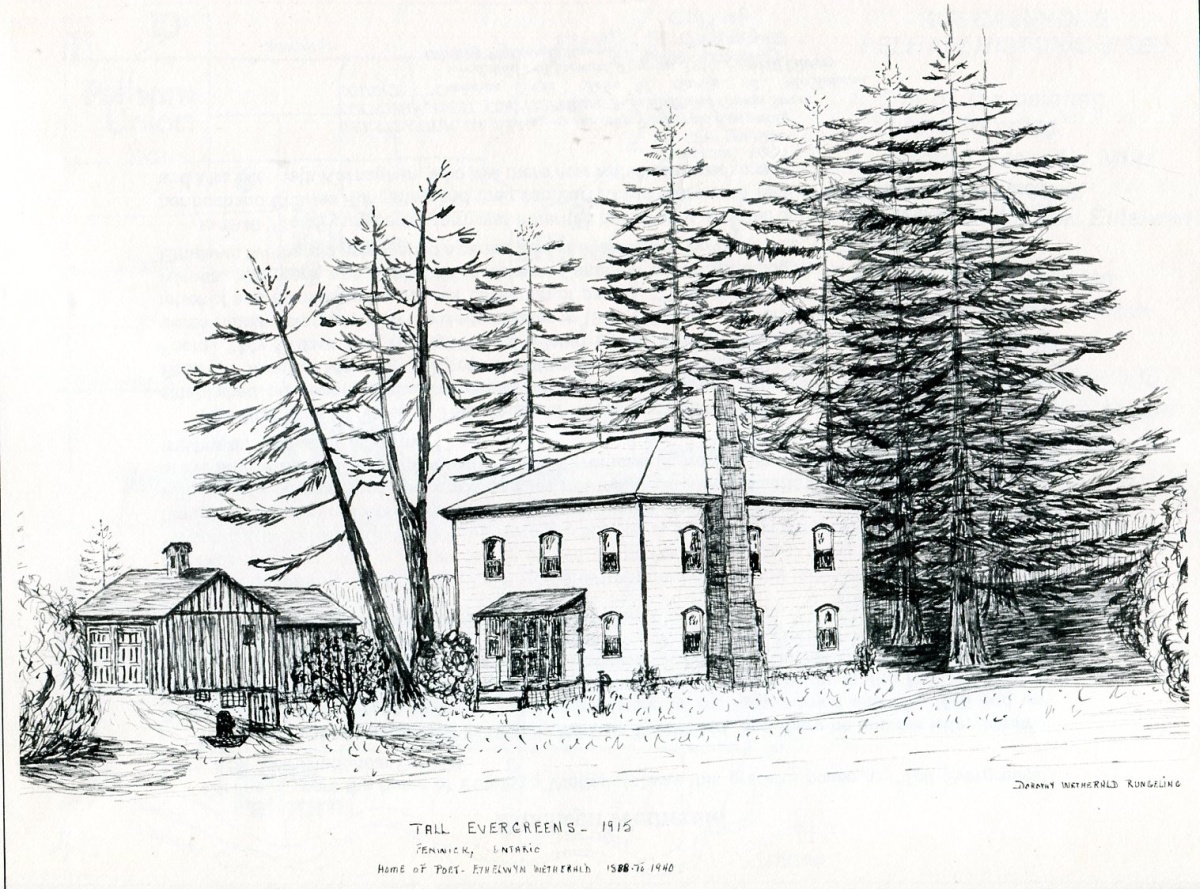

[Pelham Historical Calendar 1978]

For many years the home of Ethelwyn Wetherald was this graceful house at “Tall Evergreens” farm, a 50-acre estate near Fenwick.

The farm had been purchased in 1866 by William Wetherald, and there he and his wife, Jemima, (Harris) raised their eleven children. The original house on the farm burned down in 1888 and was replaced by this one which is still standing. Wm. Wetherald was minister at the Pelham Friends Church. Earlier, he had founded and taught at Rockwood Academy, a Quaker boarding school for boys, at Rockwood, Ontario. He died in 1898, leaving the farm to his son Herbert who lived there with a brother, William Jr. And sister Ethelwyn until their deaths.

Most of Ethelwyn Wetherald’s poetry was written here among the tall evergreen trees and apple orchards. She was nine when her family moved to the Fenwick home. “I found myself”, she wrote, “living not in an institution, but in our private home, just as other people lived. It was a thrilling thought!” Much of her work was done in her Camp Shelbi, a large tree-house built in the limbs of a huge willow in the farm orchard. Her work reflected

this delight in the rural setting of her home. A globe critic of the time wrote: “The salient quality of Miss Wetherald’s work is its freshness of feeling, a perennial freshness, renewable as spring”.

Her first book of verse, “The House of Trees and Other Poems”, was published in 1895. It established her among Canadian Poets. Other books followed: “Tangled in Stars”, “The Radiant Road”, “Tree Top Mornings”, A book of children’s poems, “Lyrics and Sonnets: (1931), and others. Her poem, “My Orders are To Fight” was quoted by Sir Wilfred Laurier when speaking in favour of unrestricted reciprocity with the United States in 1911. Earl Grey, Governor-General of Canada, wrote a letter of appreciation to her for her collection of poems, “The Last Robin”, and ordered copies for his friends. Her work was published in several Canadian poetry anthologies. A well-educated woman Ethelwyn Wetherald established a career also as a journalist. Born April 26, 1857, she died in 1940.

In 1940 “Tall Evergreens” farm was inherited by Dorothy, adopted daughter of Ethelwyn, Dorothy, her husband Charles Rungeling and their son Barry lived there until 1968 when it was sold to Professor and Mrs. Kennerth Kernaghan, who live there now with their three sons.

Book

Life and Works of Ethelwyn Wetherald 1857-1940. Canadian Poet-Journalist

By Dorothy W. Rungeling.

[Welland Evening Tribune August 1, 1978]

By DOROTHY RUNGELING

One October day in 1966 I drove past the Fenwick station (at least I drove past the site) but the station had disappeared.

Then I recalled that it was put up for sale when the Toronto, Hamilton and Buffalo Railway decided the stop at Fenwick was not necessary any loner. There just wasn’t enough business to warrant this run and so the station building was sold. But how could this possibly be? It had been there too long to suddenly be gone like this.

I had to take a second look to fully realize that it was gone. The site where the old familiar long building once stood was now just a piece of ground.

Immediately my heart did a little flip and nostalgic smells, sounds and sights came flooding to the surface of my memory, which had deeply stored them all these years.

It had been many years since I had entered the station to go on a trip, but I could sense the old excitement which a child feels when going on a train; the look around the waiting room as we entered the door, then walking up to the ticket counter with my parents to purchase the tickets.

The counter was much too high for a child to see over, but the station agent, JIM ROBERTSON and later HUGH ALSOP, could be plainly heard noisily punching the necessary information on the tickets with a flourish, as he used his big metal stamp.

Then there were the lowered voices of other passengers, making small talk as they waited for the train to arrive; the smell of soot and cinders, a delicious smell because it meant going somewhere; and the crackle of the heating system, a pot-bellied, soft coal burning stove which belched obnoxious gases into the room every once in a while.

It was usually a long wait for the train, simply because we had arrived in plenty of time, but in the meantime, I could listen to the telegraph wires clicking out their mysterious dits and dahs until at last a faint whistle was heard.

A bustle in the waiting room and excitement started to rise again at the thought of getting on the train.

But alas! It was not our train, but one going in the opposite direction. It slowed up and ran past the station at a speed which enabled the station master to convey a written message to the engineer on the train by means of a wooden hoop on which the note was fastened and then held up so the man on the train could pick it off without the train coming to a full stop. Then with a roar of the wheels diminishing in the distance, the waiting started all over again.

ARRIVES AT LAST

At last another whistle and this time we knew it was our train.

Hurrying out on the platform we noticed with approval that the arm on the high pole had been lowered by the station agent to let the train’s engineer know that there were passengers to board his train so he must stop.

This whistle grew louder, but we could not see the train yet as there was a curve in the railroad a half mile up the tracks. Then at last the big black engine loomed into sight, rounding the curve majestically.

As it neared, I covered up my ears lest the noise be too frightening. The big wheels slowed down and came to a squeaky stop as the steam let go with a mighty hiss.

ALL ABOARD

The “all aboard” signal from the conductor, always uttered with a rising inflection was the signal for everyone to get on the train. There was soot and dust on the handrails, but the green plush seats looked inviting as we vied for one with a window to press a nose against.

The whistle blew and the chug-chug of the steam engine soon started the wheels rolling again to take us on our journey with that delicious smell of soot, the sound of wheels clicking over the rail joints, the clacking and rattling of the couplings between cars which heightened as the conductor opened the doors to pass from one car to another; the excitement of new faces to look at and wonder where they were all going. And if our journey happened to be westward, the thrill of the conductor lighting all the lights in the car, which heralded the biggest thrill of all going through the tunnel at Hamilton.

In the tunnel, the darkness surged by us and I wondered if we would ever come out in the sunlight again.

Then there was the arrival of the man with the candy, peanuts, cigarettes and magazines who whizzed through the train as it stopped in Hamilton, and then another load of new faces to wonder about.

So part of the past has now been obliterated. The automobiles and airplanes have taken over the job of transportation and we have been happy about the more modern mode of travel.

But it just took a jolt, such as seeing an old landmark of the countryside disappear, to bring back in a flood, all the memories of what a steam driven train meant to a country child some years ago.

[Welland Tribune June 7, 1978]

By Dorothy Rungeling

In a pretty 42 year old house on Canboro Road in Fenwick there lives a man who, after graduating from medical school 52 years ago has his sights on becoming a “big city doctor”. Instead he has practiced for 50 years as a country general practitioner in Fenwick and has loved every minute of it.

Dr. Joe Dowd, one of seven boys. Four of whom became doctors, graduated from McGill in 1926, went to Ottawa Civic Hospital and then to New York City to gain experience in obstetrics. It was common occurrence for him to be called out at three in the morning to a house in the lower east side of New York—a tough part of town—He says: If it hadn’t been for my doctor’s bag I’d have been shot for sure,” but everyone respected the “Doc”.

It was while he was in New York that he decided this free living, bright lights life was for him and he decided he would never be a farmer’s doctor—no sir—he would be a city doctor. But fate had other plans for him.

During this time his brother Ken had purchased a medical practice from Dr. Page in Fenwick, but Ken had an opportunity to go on to bigger and better things so he fired off telegrams to Joe in New York imploring him to come to Fenwick and buy him out. Joe did.

The first week in June, 1928, Dr.Joe Dowd moved into Fenwick and started his “big city practice” in the quiet of a rural area. Shortly after this he moved his office from the Dalrymple house to the A.N. Armbrust house where he lived in a room over his office. Then he met and married his late wife,Charlotte, who was then the night supervisor at Welland County General Hospital, and they took over the whole house.

Dr. Dowd can’t recall who his very first patient was in Fenwick, but remembers that Mr. and Mrs Charlie Elliott and Mrs Grace Brown were among the first, and are still his patients. Asked who his most interesting patient was he replied without hesitation: Ethelwyn Wetherald! And recalled a story. He had instructed her to get lots of rest. The next time he called on her she greeted him with “I’ve been resting like fury!”

His mode of transportation in 1928 was a four year old Model ‘T’ Ford, but in wintertime he found himself getting to his patients any way he could, after getting a farmer to open snowbound roads. He recalls one trip west of Fenwick to deliver a baby. He had to get the roads opened, took his nurse Bernice Swayze with him, delivered the baby and then had to stay all night at the house because they couldn’t get back to Fenwick.

The Dowds had three children, Joyce, Richard and Ronald who followed in his father’s footsteps to become a doctor. In 1936 they built their new brick home. It was furnished just when Ronald was born so”my wife and Dr. Ron had a brand new house to come home to.”This was a milestone in the life of a country doctor.

During the “dirty thirties”—the depression years—Dr. Dowd found it hard going. People got sick but had no money. Nonetheless he answered their calls and took vegetables, fruit, eggs or poultry as payment. Babies were delivered at home. No one could afford the hospital. The charge was $5 a day. St Catharines General put on a “special” to induce mothers to come. It was $27 to look after both mother and child for the ten-day hospital stay. Still no one could afford it.

During his first few years in Fenwick Dr. Dowd had two to three hundred patients, but this number swelled as the years rolled by until five years ago when he semi retired.

He was our family physician for years and a good, kind doctor he was. Of course in those days there was time to be spent with a patient. Sitting down for a friendly chat before getting down to the actual doctoring was a large part of the therapy.Dr Dowd could even be talked into rendering a violin solo on my violin, although he had not played since college days. And he did a pretty good job on scraping out Humoresque on those strings.but politics was a subject to be avoided. He really had his convictions on who was right and who was wrong, and once on the subject he didn’t let go until he had panned out all the “bad ones” right out of the park.

In the thirties an office call was $1.25 and a house call was $3.00—and would you believe that this amount also covered the medicine? Yes, just a visit from the doctor and all was taken care of—physically, mentally and emotionally.

He was not one to put an elderly patient through the rigors of painful practices if he could bring them back to near normality without it. My mother broke her hip when she was in her 70s. He decided against putting her in traction. His evaluation of the case was that it would be easier on an elderly person to skip the pain, even though one leg would be shorter. A built up shoe fixed that and she lived her remaining years in comfort

Dr. Dowd is now one of the senior doctors on the staff of Welland County General and although he modestly denies it, at 82 he must be one of, If not the oldest practicing physician in the peninsula.

He thinks the most significant change In medicine in the last 50 years is the drop in tuberculosis and wiping out diseases such as smallpox and diphtheria.”Do you know that there isn’t one case of smallpox in the world today?” he asked “ “And there is no one in the Niagara Sanatarium? Thirty years ago it was full!”

Before I left I asked: “Are you still using the same cough medicine you used in the 30s?” “Sure,”he replied impishly. “My it was good,” I said. “There must have been some really good things in it.” “Sure”, he said again, but wouldn’t say what.

So, after 50 years and bringing 1200 babies into this world, Dr. Joe Dowd is quietly going on a semi-retired practice. He says he likes to look after his senior patients “because I understand them- I know their troubles—I know what to give them” He has often been known to put a patient in his own car and take them to Hamilton or Welland Hospital for surgical attendance.

A patient leaving his office as I was going in stopped to chat, and said “Dr Dowd has looked after my family for 50 years and I sure would not want to change.”

Fenwick is proud of it’s. longtime doctor., and if well wishers hold any away, he will be around another 50 years.

Subscribe..

Subscribe..