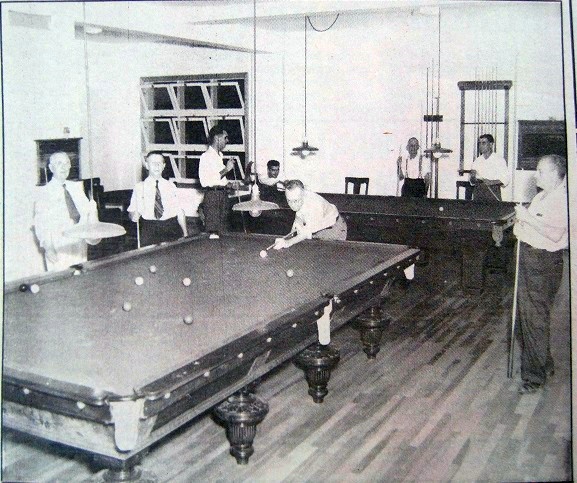

Billiard room scene in the 1940s..

[Welland Tribune, 5 November 1992]

Billiard room scene in the 1940s in the old legion hall on E. Main Street, Welland.

[Welland Tribune, 5 November 1992]

Billiard room scene in the 1940s in the old legion hall on E. Main Street, Welland.

[Welland Tribune, 5 November 1992]

First World War veterans taken in 1979 at Vimy Night. All are now deceased.

By Robert J. Foley

[Welland Tribune, 22 February 1992]

Life was hard for the ordinary farmers struggling to recover from the war of 1812. Many lived in isolation along the creeks that flowed into the Niagara from Willoughby and Bertie townships or into the Welland River from Wainfleet, Crowland and Humberstone. Rebuilding houses and barns drained what little capital they had. Most made due with the crude buildings that had all but disappeared as prosperity had come to the peninsula at the turn of the century.

The struggle to survive held the undivided attention of the entire family. Chores were complete before all else. As soon as a child was old enough to comprehend he or she was given a task, simple at first, but they picked up their share of the burden as they grew.

For us, who simply flick a switch when we want light or run down to the supermarket for our meat and groceries, it is hard to imagine having to plan carefully months in advance to light, heat and feed a household, but that is exactly what the pioneers had to do. One eye had to be kept on the wood pile. Was there enough to last the winter? Is it time to cut next year’s supply? Often if the farmer miscalculated he would have to burn green wood with the resultant smoke that inevitably would linger in the room.

The laying up of preserves for the winter was a necessary task for every pioneer housewife. The fall butchering and the preservation of meat was calculated to see the family through as well as to provide income from the sale of pork and beef to the military garrison and the growing towns.

All the cooking and heating in the pioneer house emanated from the big fireplace in the kitchen. The fire has kept blazing during the day in fall and winter as the door was often left open, despite the cold, for light and to clear smoke from the house.

For cooking purposes the fireplace was outfitted with an iron crane with hooks to hold pots. By swinging the crane out the meal could be checked without leaning over the fire. Baking was done either in a small stove fitted into the fireplace or in a crude oven built in the yard. Winter and summer the bread was baked in this manner; wood was piled into the oven and burned, effectively to preheat the oven. The ashes were scraped out and the bread inserted, cooking with the heat retained in the walls of the oven.

The utensils used in the kitchen were crude by our standards. They were often handmade from wood. Spoons, ladles and forks were laboriously carved by the man of the house. Bread pans for raising the dough were hollowed out of solid pieces of wood. The large, long handled wooden paddly used for putting the bread in and out of the outdoor oven was often cut from a single piece as well.

Health was another problem that plagued our forbearers in the 1820s. Fifty-five percent of the children did not live to age five. Doctors were often military surgeons located at the various forts around the peninsula. Doctors began to appear in the larger centres like Niagara and St. Catharines, but were too far away to be of use to most of the isolated farms and communities.

With the shortage of trained medical doctors it fell to the more educated in the neighborhood to fill the gap. These “folk” doctors, who were usually women, kept a supply of bandages and medicines obtained from the military surgeons on hand to treat their patients. They were often versed in the home remedies brought from Europe as well as those of the local Indians. These same women also acted as midwives and were sent for when the time for delivery of a baby was near.

Chronic diarrhea, dysentry and cholera, caused by the primitive sanitation, were the chief health problems threatening the populace. The local home remedy might be the only medicine available. For the above mentioned ailments this would include oak bark. The practitioner boiled an ounce of the inner bark in a pint of water and administer it to the patient. Acorns and blackberry root were also used with good results.

Children were in constant danger from diseased that are considered little more than inconveniences today. Measles and chicken pox were dangerous. Many children died of fevers brought on by teething.

Another danger facing the pioneer was the possibility of injury. Serious wounds resulting from chopping wood were fairly common. The treatment was to apply a court plaster, bind the wound tightly and hope for the best. A court plaster was made with isinglass, a gelatin concocted from the air bladders of fresh water fish and silk. Anxious watch was kept for any sign of infection that almost led to amputation of the offending limb. Before the age of anesthetics such operations were painful as well as dangerous.

The patient was taken to the nearest surgeon, usually Fort George or Fort Erie. Liberal doses of rum or some other alcohol were administered to dull the senses. Knives and saws were warmed up to lessen the shock and the doctor went to work. If the person were lucky they fainted at the first touch, sparing them the ordeal that the cutting and sawing would entail.

BY Robert J. Foley

[Welland Tribune, 11 January 1992]

Nowhere in the country had the effects of the War of 1812 been more evident than in the Niagara Peninsula. Besides the destruction of Newark and St. David’s, the town of Queenston was heavily damaged. The mills of Bridgewater as well as others had been burned by the retreating Americans or their raiding parties.

The farmers probably lost more than any others in this conflict. Many fought in the militia regiments neglecting the work necessary to grow their crops and feed their families. Fences were pulled down for firewood by both sides and many barns and houses were burned by American raiders. Refuse pits dug in the fields made some acreage untillable for some time.

The primitive transportation system was also in tatters. Roads were rendered impassable due to the heavy transports that weaved their way back and forth across the area. Bridges were burned or torn up. In present day. Welland Misener’s Bridge was burned by the British to impede the advance of the enemy. Brown’s Bridge, which was built about 1795 to cross the Welland River at the foot of Pelham Road, was also destroyed, but somehow it escaped the fate of its eastern neighbor.

The task of rebuilding was a daunting one and to many, who had started from scratch just 20 odd years before, the thought of beginning again must have been discouraging indeed.

Major David Secord stood before the ruins of his home in St. David’s. Only the chimney was left standing and a few bits of charred furniture were recognizable in the rubble. He had also lost a store and a large barn to the marauding American militia.

There was no question but that he would rebuild, beginning again. It seemed to him that his whole life had been spent starting over. One bright spot, however, was the promise of compensation for losses immediately suffered due to enemy action. The funds were to be raised by selling properties forfeited to the crown by those who had gone over to the invaders during the conflict. Still Secord was worried about the length of time it would take to pay the claims.

David Secord’s family was fortunate to have relatives in the Queenston area to stay with until a new house could be built, but many of his neighbors were under canvas with prospect of spending the winter in deplorable conditions. Major Secord knew that once the patriotic fervor over the war declined that the government might be reluctant to hand out money to those who had lately risked life and limb to save the country.

Worse yet were the families of men killed or crippled in the fighting. What was to become of them? He mounted his horse and rode back toward Queenston pondering the future of his devastated community.

While the peninsula was struggling to regain its feet with the end of the war, William Hamilton Merritt had not been idle while a prisoner of war. He took the opportunity to rekindle his friendship with the family of Dr. Prandergast of Mayville, New York, and in particular the good doctor’s daughter Catherine Hamilton, as he was usually called. Had met them when they lived near DeCew Falls and a budding romance had sprung up between the two. The romance had resulted in an engagement just prior to the move of the Prendergasts to Mayville just before the war.

With Merritt’s capture and confinement in Massachusetts for eight months he was able to communicate more frequently and on his release he headed to Mayville where he was married to Catherine on the 13th of March 1815. Merritt arrived in Buffalo with his new bride on a cool spring evening. They had come from Mayville on roads of upstate New York. Buffalo was in the process of being rebuilt and the sounds of hammers and saws filled the air with their symphony. The destruction caused in December of 1813 was disappearing under an onslaught of new lumber.

They moved on to Black Rock to await the ferry to take them across to Fort Erie the following morning as Hamilton was anxious to get home after so long an absence. The Merritts rode into Shipman’s Corners in the middle of the afternoon. The settlement along the Twelve had escaped the fate of St. David’s and had come through the war relatively unscathed. Its strategic location on the main Niagara-Burlington Road should have made it a prime target, but although some of its inhabitants were taken prisoner, including Hamilton’s father, Thomas, the buildings were spared. Merritt felt the warmth of home as he passed the church and approached Paul Shipman’s Tavern to the greeting so many of his acquaintances. They remembered Catherine from her previous stay and made her welcome. After they have been coaxed into the Tavern for a toast they headed out to the old family homestead on the Twelve Mile Creek.

William Hamilton Merritt spent a few months trying to decide what lay in the future for him. The one thing he knew for certain was that his military experience left him ill-suited for the quiet life of a farmer. The thought slowly formed.

In his mind that perhaps business was his calling. Goods of every kind were in short supply and if he could make use of the connections he had made during the war, perhaps he could become a merchant in the district. With the destruction of so many mills in the Peninsula there was money to be made there as well. He soon fixed his sights on such ventures and began to lay his plans to see them through. That decision changed the history of the Niagara peninsula forever.

Historical Notes: (1) The Bridgewater Mills were located on the Niagara River near Dufferin Islands. (2) Misener’s Bridge carried present day Quakers across the Welland River. The crossing disappeared with the building of the canal. If you go down to the foot of the Pelham Road when the waters of the Welland River are low, you will see five of the original pilings of Brown’s Bridge. They have been services of our past for 196 years.

By Robert J.Foley

[Welland Tribune, Early March 1992]

The years 1818 and 1819 were the toughest that William Hamilton Merritt would ever face in his life. The rejection of his canal proposal put his various business ventures in extreme difficulty. Hamilton’s family life was prospering at the beginning of 1818 even if business wasn’t. His pride and joy was his first born son Thomas, named for his paternal grandfather, who had been born in 1816. A little girl born in late 1817 added to the happy household.

Hamilton sat at the back of the store pondering the pile of invoices stacked in the middle of his desk. The demands for payment were becoming more adamant as the months rolled by. With the financial crisis in England and the scarcity of cash in the country there was little he could do to satisfy his creditors. The mills sat idle for lack of water and barter was the only way goods moved in and out of the mercantile.

He was sitting in idle thought when he heard a frantic calling of his name from outside the store. One of the hired hands from the mill burst through the door. “Mr. Merritt, Mr. Merritt,” the breathless man shouted, “There has been a terrible accident, come quickly.”

Fear gripped Hamilton as he rose from the chair. “A terrible accident come quickly.”

“What is it man,” Hamilton asked impatiently.

“It’s young Thomas, sir, come quickly,” he said, a mixture of fear, sorrow and horror in his eyes.

Hamilton locked the store and ran out into the cold, crisp winter night. As he approached his house he could see all the lamps ablaze and the sound of weeping rushed out to meet him.

He found Catherine, his wife, almost hysterical with grief and the rest of the household in tears. It seems that one of the hired girls had boiled some water and had set it on the table. Young Thomas came toddling along and pulled the pot over scalding himself from head to foot. He died within minutes.

The death of his son affected Merritt. A few months later the grim reaper struck once more with the death of his daughter, probably from a fever brought on by teething, which was a common cause of death in those days. We can only imagine the consternation that Hamilton and Catherine felt at his double tragedy.

With all his personal problems Merritt struggled to save the business. The farmers, who had brought goods on credit until the harvest, were unable to meet fully their commitments to him due to the poor prices of produce. Wheat only returned 50 cents a bushel at the Queenston market leaving the farmers with little or no profit. A large quantity of lumber had also been cut but lay in the yard for lack of buyers.

At the end of 1819 his partner, Charles Ingersoll, returned to Oxford County and the mercantile business closed. His father had obtained a township grant, called Oxford-on-the-Thames, on coming to Canada in the late 1790s. The township grant was revoked because Ingersoll and his partners failed to produce the 40 families stipulated in the deed, however, Charles had reacquired the old homestead.

Merritt was determined to survive and to that end he put one of his mills up as collateral to one of the Montreal merchants to whom he was indebted. Fortunately the Merritt family was a close-knit one and his uncle Nehemiah from St. John, New Brunswick gave him some assistance. His father sold the old family homestead of 200 acres for $6,000 and gave part of the proceeds to his son to help him carry on the struggle.

The year 1820 saw a turn in Merritt’s fortunes. At the opening of navigation he shipped 300 barrels of flour to Montreal assigning the proceeds to the mercantile company, Forsythe, Richardson and Company to whom he still owed money. He soon was able to clear his debts with the Montreal merchants.

At the same time he was busy drilling a salt well on his property. A chemist by the name of Dr. Chase had recently moved to the area and his knowledge soon improved the quality of the salt production. Unfortunately cheap salt from the United States made the venture unprofitable and it was soon abandoned.

The store, which had been closed since Ingersoll had left, reopened with Dr. Chase adding a drugstore to compliment the mercantile side. Uncle Nehemiah and his father-in-law, Dr. Prendergast backed Merritt in this fresh venture and it was successful beyond all expectation. Merritt was able to purchase back the mill that has been given a collateral to the Montreal merchant. With a general upswing in business things began to look up for him and the entire Niagara Peninsula.

Dr. Chase turned out to be, not only a good chemist but an excellent businessman. When Merritt was forced to assist his father who had become entangled in the failure of the Niagara Spectator, a newspaper founded in 1817. Chase went to Montreal in his place and purchased the goods for the following season.

On June 1, 1820 the family grief over the loss of the children was lessened somewhat by the arrival of a son, Jedediah, named for his grandfather, Jedediah Prendergast. On July 5, 1822 a second son was born, William Hamilton Jr. bringing more consolation to the Merritts.

With the return of prosperity Hamilton again turned his thoughts to his ditch. He began to solicit support for a second survey.

HISTORICAL NOTE: The township of Oxford-on-Thames eventually became the townships of North, East and West Oxford. The city of Ingersoll, Ontario is located at the site of Ingersoll’s grant.

By Robert J. Foley

[Welland Tribune, 8 April 1992]

William Hamilton Merritt discussed the ongoing shortage of water on Twelve Mile Creek with some of his friends, fellow millers, over a pint of local ale.

George Adams owned a mill on the Twelve as did Merritt, and George Keefer and John DeCew worked mills in Thorold. William Chisholm, a St. Catharines merchant, and Paul Shipman, the tavern’s owner, rounded out the group.

“Gentlemen, we now have raised sufficient funds to commission a proper survey for a canal from the Chippawa to the Twelve,” Merritt said. “Mr. Tibbits will come on May 6th and draw up plans. If we can achieve our goals the canal will be navigable for the numerous bateaux that ply the lakes. Also, gentlemen, our seasonal water problems will be solved.”

“How does Mr. Tibbits propose getting over the escarpment?” asked Keefer.

“He is suggesting an incline railway to move boats up and down the escarpment similar to those used in Britain,” replied Merritt.

As these sober businessmen lit up their clay pipes, an uncharacteristic sense of excitement, perhaps brought on by the unknown, the prospects that they could not foresee, gripped this small group of visionaries.

Tibbitts arrived on schedule and he and Merritt inspected the Twelve Mile Creek from its mouth. “Well Mr. Merritt, I quite agree that the Twelve is well suited to navigation and I would suggest that we also use Dick’s Creek for our approach to the escarpment,” said Tibbitts.

The two stood looking up at the escarpment and the climb that would be necessary to the top. Tibbitts scratched his chin and said, “I fear that an incline railway may not be practical to climb this mountain. Locks may be the only answer available to you.”

They were joined by George Keefer at the top of the escarpment and together they walked the proposed route to the Chippawa. Satisfied with the information gathered, Mr. Tibbetts worked up a rough plan in anticipation of a proper survey.

While the survey was being completed Merritt went to inspect the Erie Canal to get a first-hand perspective of what they were about to embark on. He left for Lockport, New York on the 19th of July, 1823, and met with Roberts the head engineer on the Erie. Roberts gave him a certificate of efficiency for Tibbitts that reinforced his own opinion of him. He spent several days inspecting freight boats and construction methods.

The more he waw, the more the feasibility of their project became apparent. The timing was also excellent as many of the contractors were winding up their portion of the Erie Canal and could begin work on the Welland Canal almost immediately.

On Jan. 19, 1824, the Act passed the Legislature Assembly incorporating the Welland Canal Company with William Hamilton Merritt, George Keefer, Thomas Merritt, William Hamilton’s father, George Adams, William Chrisholm, Joseph Smith, Paul Shipman, John DeCew among others as director. Plans for financing the project got under way immediately.

Meetings were called throughout the district to sale the shares in the company. The fundraising ran into problems from the onset. People in Niagara (Niagara-on-the-Lake) would gladly purchase shares if the canal began at Niagara. The merchants of Queenston insisted that the entrance would be best there. Because of this bickering the shares did not sell well in the peninsula. The company decided that it would have to go further afield to finance the project.

It was at this time that tragedy struck the Merritt family. In early February, Hamilton’s older sister Caroline and her 13-yer old daughter along with a Miss Stephens arranged to go across to Lewiston, N.Y. on the ferry. The ferry was just a large rowboat and as they crossed the river a large ice flow struck the boat capsizing it. Miss Stephens and the girl were swept away and never seen again. Caroline was rescued but died of cold and exhaustion shortly afterward.

Mourning the loss of his sister, Merritt headed for Montreal and Quebec City in March to set up committees to solicit shareholders for the company. On his way, he stopped in York and received a pledge to buy stock from the Receiver-General of Upper Canada. J.H. Dunn, who also agreed to take on the position of president of the company.

Despite all the well-wishes and praise for the project, funds were slow in coming in. Added to that was the engineer’s disturbing news that too deep a cut would have to be made to use the waters of the Chippawa forcing the building of a feeder Canal from the Grand River. The feeder was to cut 27 miles through the Cranberry Marsh and carried via an aqueduct over the Chippawa near the Seven Mile Stake. These circumstances forced the company to postpone construction until all the shares were sold. In the meantime the surveyors completed their work from Thorold to the Chippawa and began the survey of the feeder.

In June, George Keefer was elected president of the company in place of Dunn and Hamilton was authorized to seek funds in New York City. The New York financiers were more than interested but insisted on a change in the plans. The canal was to be designed to carry larger steamers as well as the smaller bateaux. The New York trip was a rousing success and on Nov. 15th the first contracts were let. The great enterprise was about to begin.

HISTORICAL NOTE: The nature of the name Seven Mile Stake is uncertain, however it may have been the surveyor’s stake marking the northeast corner of Wainfleet Township.

By Robert J. Foley

[Welland Tribune, 13 April 1992]

The spring of 1825 brought new life to the Irish laborers who worked in the deep cut. The ankle deep mud was better than the bitter cold of the winter for those shovelling their way to the Chippawa. The teamsters cursed the muck, however, as their horses strained to keep the heavy wagons moving.

There were sections where the muck had to be carried to the top by hand. Men with hundred-pound sacks on their shoulders struggled up the slippery slope to load wagons that would get bogged down in the bottom. Many a man lost his footing and tumbled back to the mud below. If her were lucky he lifted the sack to his shoulder and started again, but many were injured, losing their jobs. There was no such thing as workers’ compensation to feed the sick and injured. No work, no pay was the cruel reality that they faced each day.

The canal was divided into 35 sections. Each section had a foreman. Fifteen laborers and six teams of horses. Some of the laborers worked with picks to loosen the earth while the others loaded the wagons with shovels.

John Phalen wiped the perspiration from his eyes that ran down from his hairline despite the cool temperatures. He leaned on his shovel for a moment while the foreman inspected the rock that impeded the work.

Phalen knew that if he were caught resting he would get a tongue lashing. The pain in his side that had kept him in agony for weeks was under control thanks to another laborer with knowledge of such things.

Phalen was suffering from a rupture, but the fellow had been able to fix him up with a crude truss that gave him some relief. He had to keep working for the sake of his wife who was expecting a baby any day. With two other children to feed, he could not afford to lose any time.

The foreman came away from the large boulder muttering about delays. The rock would have to be blasted with gunpowder.

“Phalen, get the drill, we’ll have to blast this one. Larkin, go and draw the explosives.”

Phalen shuddered as he pulled out a hand drill from one of the wagons. Blasting rock was always a tricky business. Just last week Frank Murphy, who lived tow shanties down from him had been blown to bits when the charge had gone up in his face. He had been the one to take the news to his wife.

The men took turns to drill a deep hole that would shatter the rock into manageable pieces for loading onto the wagons. This did not mean a respite for the others, however, as the foreman, constantly aware of the deadline for completing his section, drove them on, digging around and beyond the offending morsel of granite.

Finally the hole was pronounced deep enough and the crew was ordered up to the top out of harm’s way. The only man to be left below was to be Patty Larkin to set and light the charge. Phalen could see the glassy look in Larkin’s eyes. He had taken on too many sips from the “water” boy’s bucket and was half drunk. In his condition he stood a good chance of going up with the rock. Before he could think, he heard himself say, “Let me do that Patty, you get up top with the others.”

Phalen turned away from the look of relief on Larkin’s face. He began to place the charge carefully in the hole trying not to think of Murphy’s crumpled body lying in the mud. He lit the fuse and ran for the slope climbing for his life. Half way up the pain struck him like an axe and he slipped. For a moment he couldn’t move. He was sliding back down toward the bottom. The men at the top must have sensed a problem for despite the danger, several heads popped over the edge and began to call to him. “Hurry, John, hurry.”

Phalen struggled to reach the lip of the ditch in spite of the pain. As he neared the top, several hands grabbed him and pulled him over just as the thundering explosion shattered the air.

Phalen lay on his back gasping for air. The pain in his side was only a dull throb now. The foreman stood over him. “Are you all right, Phalen?”

“I’m fine, just slipped that’s all,” he lied.

“Well then, get off your back and start loading up that mess you made down there,” he said, a rare smile on his face. Maybe the foreman was human after all.

The backbreaking work of excavating the deep cut was carried out under conditions that we would be unable to comprehend. The cut was an average of 44-feet deep in the 1 ¾ mile stretch between Allanburg and Port Robinson.

In July, 1826, a newspaper advertisement offered wages of $10-$13 a month and boasted that only three deaths had occurred in the previous month. Single men could rent a room at a boarding house for $1.50 per week. This amounted to half their pay. A man with a team was paid a few dollars more. The men with families built shanty towns along the route picking up and moving as the work progressed.

Because of the lack of safe drinking water the “water boys,” that moved up and down the line carried buckets of raw whiskey. This thirst quencher was ladled out in tin dippers. As a result of this, accidents and violence were common place.

Disease was another problem facing the workers. Bad water and poor sanitation bred cholera, dysentry and a myriad of other maladies that killed the men and their families by the hundreds.

The Welland Canal was not built by the merchants, bankers and investors. It became reality by the sweat, blood and lives of thousands of men, mostly Irish immigrants seeking a better life for themselves and their families in a vibrant young country that was to become Canada.

It was make-or-break time as farmers eyed the weather

By Robert J. Foley

[Welland Tribune, 9 March 1992]

The most critical time of the fall for the farmer was the harvest. On this hinged his livelihood and the survival of his family. Would an early frost damage the crop? Would the rains hold off until the fields were cleared? All these things plagued the pioneer as he waited for his crop to open.

In preparation for the harvest the equipment had to be inspected and repaired where necessary. Sickles and scythes were sharpened and flails made ready. Sweeping the barn floor to prepare it for threshing was a job for which the children took responsibility.

With one eye on the weather the farmer walked his fields checking the grain to satisfy himself that it was ready for harvesting. If he didn’t have children old enough to help with the cutting and gathering, he would hire some farm laborers from the nearest town or, if the weather was holding, neighbors gathered and helped each other bring in the crops.

Haggai Skinner looked over the flowing field of wheat that was about to be cut. He let his mind wander over all that he’s been through in the last seven years. He had been working this very field in 1813 when the American patrol had snatched him up and made him a prisoner-of-war. It angered him still when he thought it. At 64, he was exempt from militia service, yet they had taken him anyway. For almost a year he had languished in prison to be repatriated in July, 1814, in time to hear of the bloody battle at Lundy’s Lane. He arrived home to find the family in mourning for Timothy Skinner who was killed at the Battle of Chippawa earlier in the month. He was buried somewhere on the battlefield. The American refusal to allow the recovery of the dead after the battle was something else that rankled Haggai. He had gone to the battle site after the harvest that year in a vain hope of finding a clue to the burial spot, but found nothing.

He was roused from his musings by the impatient stamping of the horses who seemed anxious to get started. Seeing the boys ready to gather the cuttings into sheaves he began to swing his sickle in a smooth, rhythmic stroke developed over 60 years of farming.

As the grain was cut the workers following behind gathered them into sheaves and loaded them on the wagon for transport back to the barn. The work day began at first light and except for meals, went straight through until sundown. Often lunch was brought to the fields so as to lose as little time as possible.

Once cut, the grain was moved to the barn for flailing. The flail was made up of two sticks each about three feet long. A leather strap or a piece of rope joined these together. The grain was laid out on the floor and the men began beating the stalks to separate the grain. Once this was completed, the stalks were gathered, shaken and discarded.

The grain was swept into a broad wooden shovel with a handle on either side. In a process called winnowing, the grain was tossed in the air, allowing the chaff to blow away while the heavier grain fell back into the shovel. We can imagine the field day that the farm poultry had snatching up the grain that invariably fell to the ground. The grain was then bagged for the trip to the mill or to sell as whole grain.

Wheat most often went to the mill to be ground into flour. Oats and barley were usually sold for feed or, in the case of barley, to be made into beer or liquor at one of the local brewers or distillers.

Transportation to the market was a thorny problem in the 1820s. In Humberstone and Wainfleet, the mills at the Sugar Loaf had to be reached over swampy terrain. In Stamford, the Bridgewater Mills, burned by the American in 1814, had not been rebuilt, making the long trek to either the mills in Thorold or to the Short Hills.

If heavy rain fell, the roads became impassable and often the crop had to be moved in other ways. Those on a waterway sometimes tried to float the grain to the mill, however, this often led to a soaking leaving the grain useless for milling.

The mills in the Niagara Peninsula were water-powered. The grain was poured into a hopper and was grounded between two large stones. The flour dropped through a meal trough and was packed in barrels for storage and shipment. Payment for the milling was often made by giving the miller share of the grain. The miller would also would act as the farmer’s agent in the sale of the ground grain as well.

In order to produce an adequate grade of flour the mill stones had to be sharp. It was necessary from time to time to deepen the furrows in the wheel and to dress the surface. A crane was used to lift and turn over the upper stone. The furrows were then deepened with steel picks to bring them up to spec. To test the levels of the stone a wooden bar with its edge smeared with red clay was drawn across the surface. The high parts with red clay smeared on them were then dressed off until the surface was level.

The next problem facing the millers and merchants of the peninsula was moving the flour to market. Produce from Humberstone and Wainfleet moved by water down the Welland River to Chippawa and then along the Portage Road to the busy port of Queenston. From here freight for every type was loaded on sailing vessels for York, Montreal and Quebec City.

*Historical Note; Haggai Skinner’s farm was located in Stamford Township in the vicinity of present day Mcleod Road and Drummond Road.

By Robert J. Foley

[Welland Tribune, 9 March 1992]

In the early 1820s the peninsula was still struggling to re-establish the industries decimated during the war. A deep recession that followed the conflict slowed the process greatly as we have seen in the problems encountered by Merritt.

On the site of the Battle of Lundy’s Lane a small community began to grow. Austin Morse was a furniture maker and undertaker whose chapel still operated on Main Street today. Andrew Moss made cabinets, James Skinner was a harness maker, John Misener ran a wagon building operation and William Gurnan was the indispensable blacksmith.

One of the more prolific endeavors of those days was the distillery. One such operation was located at the foot of Murray Street in Queen Victoria Park. It was a stone structure and was there to take advantage of the spring that ran down the ravine. It was abandoned in 1826 and eventually housed Barnett’s Museum.

St John’s, near Fonthill, was one community that had escaped damage during the war and prospered. It boasted many mills and a number of distilleries. An iron foundry, tannery, saddle maker, a woolen factory and many others rounded out this thriving town. The Welland Canal put St. John’s into decline as industry moved closer to the canal banks and today little remains of its former glory.

In the southern part of the peninsula the Sugar Loaf sported a community that included saw mills and grist mills. It also had a blacksmith, harness maker, furniture maker and the inevitable distillery.

One of the most important workmen in the community was the blacksmith. The first thing pioneers demanded upon arriving in the peninsula in 1781 was the services of a good smithy. We always associate the blacksmith with shoeing horses, but his business went far beyond that. He made everything from door hinges to wagon wheels.

The blacksmith shop was a miniature factory. The heart of the shop was the forge that was made of brick. It was set on a stone foundation with a square brick chimney that went up through the roof to a height of four feet above the ridge pole. The hearth was a square box 12 inches deep set next to the chimney. The bottom of the hearth was a slab of iron with a hole in the centre to take the air nozzle or tuyere as it was called. The tuyere was a hollow, slotted iron bulb attached to a pipe leading to the bellows. Air could be directed to one side of the hearth or the other by the use of an iron rod that rotated it. The brick work was extended to form a table on which the smithy could organize his work or leave finished pieces to cool.

The bellows was a huge leather lung eight feet long and four feet across that was mounted behind the chimney. A large stone was placed on the top so as to create a constant pressure allowing a gentle stream of air to keep the coals hot. If the smithy needed a little extra heat he pulled vigorously on the wooden handle that was attached to a chain and extended to the front of the forge.

If the forge was the heart of the shop then the anvil was the soul. It was a 250-pound block of iron that measured 5 inches across, 20 inches long and had a 16-inch horn curving out from one end. Its top was a slab of steel wielded to the wrought-iron base. Two holes were cut in the rear part or heel of the anvil. The hardy hole was square to fit the many forging tools used by the smithy. The pritchel hole was three-eighths of an inch and round. It was used for punching jobs such as knocking nails out of old horseshoes.

The placement of the anvil was very important. Because the iron had to be heated at least once, if not more, the anvil had to be close to the fire. It was usually placed with the horn facing the fire. The height of the anvil was also critical. The black-smith custom-fitted his anvil to match his needs. If it was too high he would wear himself out swinging his hammer; if too low his hammer would not strike the iron squarely ideally, the bottom of the smithy’s natural hammer swing matched the height of the anvil.

The setting of the anvil was an exact science, for once in place it could not be moved. It was mounted on top of a post that was sunk four or five feet in the ground. With his anvil in place and coals glowing red in the hearth, the blacksmith was ready to do his work.

The iron that the smithy worked came from a bloomer furnace and showed a crystal structure. After forging, the crystals formed a grain that allowed the iron to bend without breaking.

The blacksmith often had to draw the iron to make it thinner and wider. Heating the iron until it was red hot, he then swung it to the anvil and struck it with his set hammer until it was no longer pliable enough to work. He would repeat the heating operation until he was satisfied that he had a workable piece of material.

The peninsula was coming of age, The Welland Canal was about to come a reality to change the loves of all who dealt in its shadow.

By Debra Ann Yeo

[St. Catharines Standard, 1992]

Staff Photograph by Mark Conley

Staff Photograph by Mark Conley

They had no obligation to fight in the War of 1812.

Most were former slaves, and few owned land-the criterion for compulsory military service.

Some of their race were still enslaved in Niagara despite a clause in the Upper Canada Act that legislated partial emancipation.

They were: ”Robert Runchey’s corps of colored men ”believed to be the first black unit in Canadian military history.

Only 25 to 50 men strong, they fought at the battles of Queenston Heights and Stoney Creek and against the American siege of Fort George in 1812-1813.

Their contributions to the history of Niagara and Ontario are to be honored with a historical plaque.

The proposed location is Regional Road 81 ( Old Highway 8 ) more than a kilometre east of Jordan-where Runchey’s home, inn and stage-coach stop once stood.

Paul Litt, a historical consultant with the Ontario Heritage Foundation, said Runchey’s men were the only all-Black corps to fight in the War of 1812.

“It shows there was a distinct black community in that area of Ontario at that time, much easier than most people thought. “

“They had enough interest in the British cause to organize to help them in the war,” said Litt.

Jon Jouppien, a member of the committee that proposed the plaque in 1987, said the volunteer soldiers’ contribution to history “sort of fell through the floorboards of time.”

“You would never know they existed,” agreed Al Holden, chairman of the Niagara Heritage Commemorative Committee and an unpublished author of Niagara military history.

Yet, Holden said, the soldiers served “with distinction” at Queenston Heights, part of the first advance against the Americans.

It was Richard Pierpoint, a former slave who was one of the first few black landholders in Niagara and one of the first settlers in what is now St. Catharines, who organized the company.

Since there were no black army officers, Pierpoint, a private, wasn’t allowed to lead the corps. It was Runchey, a white man and member of the first Lincoln Militia, who was given command.

Even though he led the company less than a year, they were known throughout the war as “Runchey’s company of colored men.”

Most had escaped slavery in the U.S. Some had served with Butler’s Rangers during the American Revolution.

Most resided in Niagara, although some came from York (Toronto) where they had joined the militia.

Holden tells a tale of one slave named Jack who fled his Grimsby masters to join the company. He was turned away when his owner came to claim him.

Despite the Upper Canada Act, slavery was not officially abolished in Canada until 1834 when it was banned throughout the British Empire.

Runchey’s men were headquartered in Niagara-on-the Lake during the war but segregated from the white troops.

By 1814-the year they finally got uniforms of black gaiters, green jackets with yellow facings and felt caps with plumes-they had become artificers, excavating earthworks and doing other engineering jobs around Fort George.

Records obtained by Holden from the national archives show 14 of Runchey’s men were dead by 1820, at least 10 were still in Niagara, seven deserted during the war and at least two died in battle.

Volunteers who had kept their posts and lived were granted land for their service.

By 1819, Runchey was also dead. His house stood until the early 1970s’ when it was demolished after a fire.

Although the committee hoped to erect the plaque to coincide with Jordan’s Pioneer Day, Litt said, it’s too late to make the Oct. 17 date.

A second provincial plaque honoring Harriet Tubman will be erected in St. Catharines in February 1993, which is black history month.

Tubman was an escaped American slave who lived in St. Catharines from 1851 to 1858, according to the St. Catharines Museum.

Nicknamed Moses, she made many dangerous trips back to the U.S., guiding a least 300 slaves to freedom in Canada along the famous Underground Railroad.

The home she rented on North Street, which is no longer standing, was used as a boarding house for the escaped slaves.