Results for ‘Historical MUSINGS’

[I found this interview in my father’s files and thought it appropriate to share at this time.]

Date of Interview 1990

Mr. Crouch was a dedicated and well-respected lawyer in Welland. He passed in 2010 after working 43 years at the Flett Beccario Law Office.

Sidor Crouch (Born in Russia 14 May 1895-26 June 1980).My father was one of the founders of the Deere Street Hall.

When the Ukrainian immigrants came to Welland, they were fragmented. As in all groups, some were religious some were not…In the case of the Ukrainians, they divided into four parts, as far as I can remember. There were the Greek Orthodox believers…the Greek Catholic believers…there were those who sympathized with Communist regime and the Soviet Union and they ended up with the Ukrainian Labour Temple, together with many others who were basically interested only in the educational and cultural life in the Labour Temple…and then there was another group that didn’t fit into any one of these other categories. They ended up in the Deere Street Hall. My father was one of those.

It was organized about 1920..They were non-believers. They had gone through a period where the Church had not been particularly an attractive influence. It had sided with the feudal aspects in Russia. So they preferred not to be associated with the Church. And also they weren’t comfortable with the sympathizers with the Communist regime. Some were Socialists-social democrats-a very few might have been anarchists-and some were people who weren’t any religious or political philosophy-“Well the Deere Street Hall doesn’t take a strong stand on any of those, let’s go there.”

While you’re in an ethnic group, you want to belong to some group; you want to belong to some group where you can go and dance and see drama. I suspect most of the members were in that last category, without strong religious or political beliefs.

JB: Was your father an anarchist?

PC: I use to be puzzled as a young boy, listening to my father argue. I think my father just liked to ague. My father read a great deal even though he’d had a limited education. He read Peter Kropotkin books a form of anarchy with no violence. My father, when he flirted with anarchism flirted with the non-violent aspect of Peter Kropotkin. I remember we had that book in Russian in our home. It was amazing to me that my father, who was a working man with three years of education, should be reading these philosophical books. My father wasn’t sure what he wanted to be. He finally found his niche when the CCF was founded. I think he thought about anarchism; I don’t think that was a serious part of his life.

Father was born in Ukraine, born in the Eastern Ukraine. 99% or more of the Ukrainians who came to Canada came from the Western Ukraine. That influenced him; made him different from other Ukrainians in Canada. The other ones were Greek Catholics and much more nationalistic. Ones from Eastern Ukraine spoke Russian as well as Ukrainian. Those who came from Western Ukraine were recruited, helped with some financial assistance. My father came from the Tzarist Iron Curtain. My father came as a 17 year old…smuggled himself across the border, in the dead of night, along with several other young men. They came without permission of the Russian government and without financial assistance.

He left Russia because he worked as a lackey for a feudal landowner. And one day, my father was polishing boots for this man-and the man was unhappy with the way my father had polished his boots, and so he threw the boots at my father-told him what a poor job he had done. My father went home to see his father and said he’d had enough. That he understood there was a better country-that was Canada-he knew one person in Welland, Ontario. He asked his grandfather for money and made his way across Europe, country after country, without being able to speak the language. Finally found himself in Hamburg, Germany and took a ship to Montreal. The immigration agent asked him what his name was, he said Krawitz-which means tailor, one of the most common names in the Ukraine. The English immigration agent didn’t know how to write Krawitz, so he put Crouch down. Many immigrants had their names changed.

He had one friend in Welland. He worked and then joined the Canadian army. He served at and was wounded at Vimy Ridge. We were always proud of that. After war, he came back to Welland and helped found the Deere St. Hall.

The hall didn’t really have a specific aim. It’s purpose was not clear And without a purpose, it didn’t continue. Eventually, the members found their way to the three other organizations.

The hall had a band, drama, concerts, masquerade parties. A particularly welcoming place. People could feel at home with each other and enjoy themselves. I was taken to the hall with my parents. There were no babysitters. The immigrants who came wanted their children to retain the Ukrainian language but it was a losing battle. The children would be assimilated.

In my family, it was difficult to retain the language because my mother immigrated when she was eight, father came at 17. Easy for them to switch to English. Mother was of Ukrainian background. She had emigrated in 1913 to the U.S. with her mother. There was a shortage of women in the U.S, and Canada for immigrant men. It was not unusual to invite women over. Mother’s mother-a widow-had been invited over. She went to Pennsylvania. Mother had a Greek Orthodox background. My parents met at a wedding in U.S. and wrote letters but they never dated-he proposed by mail 69 years ago.

Mother came to Welland then which was a great culture shock, plus she had to learn to cook and be a housewife. An older woman helped her out. My mother remembers her kindly.

JB: Did she go to the UK. Halls?

PC: She liked the social part. But soon, they started having children. And there was a lot of work around the house-where she still lives. Mother had too much work to do to go to the hall. The men would go there for meetings.

Eventually the hall was sold and became a church for a very short time. I was amazed when I went back once at how small it actually was. As a child it seemed a sizable hall. I don’t know what’s there now on the north east side of Deere St. It stopped operating by the late 30s’. I think there was a polarization. Some ended up at the two churches, others at the Labor Temple and some went nowhere. In our case, we didn’t go anywhere. We weren’t comfortable in any of the other places. But at times we ended up at all three of the other places, for social events. But we were not members. That accentuated our assimilation.

My father was an atheist. He never wavered. At that time, religious differences seemed very important. Those who were firm believers were not very friendly with those who were atheists. As the years went by, they forgot their differences.

Politics is important to [ post-war immigrants], politics in the sense of nationalism, of an independent Ukraine. That was their most important political belief. There wasn’t an active interest in Canadian politics. They were looking back to Ukraine. Among those who came in 1913, there was a great longing for an independent Ukraine, for a long time.

JB: Where did your father work?

PC: Page Hersey, Inco, Welland Electric Steel Foundry, he was an assistant melter. He became the melter and was the second man in Canada to make stainless steel. And that’s quite an achievement. He worked there the rest of his life. He was also a self-taught electrician.

The other immigrants looked up to my father as a very intelligent person, “book person”-he read newspapers. He became the president of the Crowland Tenants and Ratepayers Association. He organized concerts, after the Deere St. Hall had ceased.

Father believed all nationalities were important, not just Ukrainians. All of his children married non-Ukrainians, which was not typical. None of us married within the Ukrainian community. That was highly unusual.

JB: The RCMP, did they watch your father?

PC: If they did, I really wasn’t aware of it. There were all kinds of rumours at that time, that the RCMP was watching people who weren’t the conventional people but there’s no way I would know.

Asked my mother if she knew of any anarchists-mother said she would be hard put to think of anyone who was an anarchist. They had speakers who would come to the Hall. Who came and spoke on anarchism. Well. I suppose once you‘ve had a speaker-at that time-that was enough to set off the RCMP, the name of the organization would be blackened. I knew many of the people there. I think they belonged to the hall because it was a social place to be. I don’t really think that they ever really read an anarchist book in their lives. I think an anarchist was a very rare people indeed.

There was no military in the Deere St. Hall. They would bring in speakers. There was more an attempt at an intellectual approach to these things. You didn’t find union organizers there. You found that at the Ukrainian Labour Temple. The labour leaders from the Welland area emerged from the Ukrainian Labour Temple, not from the Deere St. Hall. Although the name “labour” appears there [in title of hall]-they weren’t militants.

My views on discrimination. I remember as a child the discrimination, acts of discrimination felt by the Ukrainian community and by all ethnic groups. It was difficult for n ethnic to get a job as a foreman or a supervisor or a teacher. I was very conscious of that. As years have gone by, what I’ve realized,-and I was a little bitter about that at one time-but as years have gone by, I’ve put it in perspective. And it’s this. Whatever country there is, there will be discrimination. It’s a natural course of action. Had the English immigrated to the Ukraine, they would have been as discriminated against as the Ukrainians were when they came to Canada. It’s a natural thing, and in a short period of time-how can I possible complain about discrimination when in a very short period of time, ..I have had this upward mobility in this country. Where else could you go, with a mother and father hardly educated when they came-and there their children prosper and we have prospered? My initial bitterness has changed to an appreciation of the country. Best jobs wen to English speaking. Only the poorest jobs went to the ethnics. We were called Hunkies, but it happens in every country. Now we’re a country where we still have decimation of course, but it’s a country where you can come as an immigrant and still achieve considerable status and prosperity, perhaps much better than any other country. I’ve always been grateful that my mother and father decided to come to Canada. They had a hard time but it’s a wonderful thing for their children that they decided to come to Canada.

Father had a great belief in education, he believed I would go to university, not work in a factory. None of us [siblings] went to work in a factory. And that was unusual in the Canadian/Ukrainian community. Father was an intellectual in a working class environment.

We don’t celebrate Ukrainian holidays. We became assimilated more readily. I can read and write Ukrainian and Russian, to translate letters when they come from the Old Country-I have twenty first cousins there-but we don’t go to the Ukrainian Church, or any other church. Sometimes go to the one near my mother, All People’s Church. My brother is active there. My children can hardly speak a word of Ukrainian.

My father died 10 years ago. He was 85 then. We were very proud of his accomplishments. On his tombstone it says “A good husband, father, grandfather and citizen.” He was extremely well regarded in the community. Initially, it was not so because there were those divisions in the community. But as the years progressed as people decided the political and religious differences were not that important, and as my father became active in the community-concerts and ratepayers association-he achieved quite a status.

[Article - submitted by Karen and Donald Young, daughter and son-in-law of Eric Waterfield.

Eric Waterfield was born in Woodstock. He graduated from the Pharmacy program at the University of Toronto in 1941. He trained as an officer for the Canadian army and was stationed in England, but never saw active duty.

Eric Waterfield was born in Woodstock. He graduated from the Pharmacy program at the University of Toronto in 1941. He trained as an officer for the Canadian army and was stationed in England, but never saw active duty.

His pharmacy career began in Toronto, and then he purchased the former Wyllie Theal Drug store at 30 Niagara Street in 1951.The pharmacy name was changed to Waterfield’s Pharmacy. He put in long hours at the store including evenings. He would come home for supper and then return to the store.

In 1975, he sold the store, but continued to work for another three years at the Lewis and Krall pharmacy until 1978 when he retired.

Eric lived with his family at 131 First Avenue in Welland. He died in 1991 in his 74th year, and is buried at the Pleasantview Memorial Gardens in Fonthill with his wife Beatrice who died in 1990. Eric and Beatrice had three children, Ann, Karen and Rob.

Eric was an active golfer and a member of the Lookout Point Golf and Country Club since 1951. He was a member of the Welland Rotary Club. When Wesley United Church was established, Eric was a charter member.

[TODAY’S SENIORS, June 1990]

By Peter Warwick

The roar of diesel engines has replaced the clatter of trolleys along the streets of Welland, but memories remain. From 1912 to 1930 streetcars operated in Welland under the name of Niagara, Welland & Lake Erie Railway Co. {N.W & E).

Organized in 1910 by C.J. Laughlin Jr. of Page Hersey Tubes Ltd. (now the Steel Company of Canada), which owned the company as long as it operated, the N.W. & L.E. was incorporated in 1911.

While it was to have been an interurban line connecting Niagara Falls, Port Colborne, Fort Erie, Dunnville and Port Dover, it never got out of Welland.

Had the Niagara Falls –Fort Erie part of the line been built, it would have been in competition with the Niagara, St. Catharines $ Toronto Railway, then being built through the same area.

A standard 20-year franchise was granted the railway by town council July 4, 1910, construction of the line started in fall of 1911, with the first spike being driven by Mayor Sutherland of Welland on October 4.

Operations began March 24, 1912 on 1.74 miles of track using three streetcars built in Springfield, Massachusetts. Car barns were located at 30 Main Street South. The line ran North along Main Street South {now King Street} from the Michigan Central Railway {now PC Rail} to Main Street East and along Main Street East to the Grand Trunk Railway (now CN Rail). The fare was 5 cents or 6 tickets for 25 cents and cars operated every 15 minutes.

When the streets the line operated on were paved with brick. In 1913, the N.W & L.E.. agreed to pay $3,000 annually to the town for 20 years, the estimated interest on the money Welland borrowed to pay for the company’ s share of the paving. It also relieved the company from paying property taxes except for school taxes.

Extensions were built in 1912-13 on Main Street West to Prince Charles Drive and on Main Street North (now Niagara Street) to Elm Street, but were not operated at this time due to weight restrictions on the Alexandra Swing Bridge over the Third Welland Canal. Other extensions were proposed on Main Street East to Rosedale, about one mile, and on Main Street South to Dainville, about two miles, but these were never built.

The weight restrictions on the canal bridge were overcome in 1922 when two new, lighter trolleys were acquired and the West and North Main extensions were operated for the first time, increasing the company’s mileage to 2.9 miles. Service was reduced to half hourly. Since the extensions were only a few blocks long, they proved a disappointment with the passengers and service was abandoned after only six months of operation.

While the line was primarily meant to transport people from one part of town to another, at least one mother used the trolley to babysit her young daughter. The child was put on one of the streetcars and placed in the care of the conductor who looked after her until her mother was through shopping or visiting.

The peak year for the N.W & L.E. was 1917, when 693.843 passengers were carried and for the net income of $16,262. Thereafter traffic and income declined and in 1929, the last year for which statistics are available, only 320.118 passengers were carried for $775. Despite the small size and the 5 cent fare, which remained in effect until abandonment, the company never suffered a deficit.

Efforts were made to sell the streetcar line to the city for $1 before the franchise expired, but this was turned down and on July 4, 1930 the last trolley ran. A substitute bus service was started by F.I. Wherry of St. Catharines, but it too ceased after operating only a couple of weeks. The National Trust Company of Toronto, which had held a trust mortgage on the company for all of its life, was appointed receiver.

Today nothing remains of the line except for a few pictures, maybe a few tickets and lots of memories for the people who rode the streetcars.

By David l. Blazetich, from the files of his grandfather George “Udy” Blazetich

[Date Unknown]

In 1913, the Laughlin realty Company produced an advertisement to promote its interest in selling land in Welland. Large and obviously designed to promote the company’s expansion in Welland, the circular nevertheless contained much information of historical value and some now-rare photographs.

Under very large, major headings such as: “Why Welland Grows”, “Railroads and Banks”, and $50,000.000is being spent on the New Welland Canal and Welland Has Made Good”, the circular gave detailed information and a map outlining industries and points of interest in Welland, a city that is today making history.

It goes on to praise the “factories that have sprung up and are running where a year ago were vacant commons. New paved sidewalks have been paid out and completely built up. Main business and residence streets are paved. A street railway was absolutely needed and built in several months-now in operation. And this growth will keep on. More homes are right now needed for workmen coming to locate.”

It confidently predicted “Welland is destined to become one of Canada’s greatest industrial centres,” and “with its several railroads connecting it with cities like Buffalo, Hamilton and Toronto clustered around it-with its power at rock bottom price-its cheap natural gas-with the new $50,000,000 canal, there is absolutely nothing to hold back Welland’s growth.”

Specifically promoting the Manchester Park development, it asked: “What would it have meant to have bought several lots in Toronto a few years ago as close to Young Street as Manchester Park is to the Post Office in Welland- -10 minutes’ walk? The article said, “Many men in Welland have grown rich during the past few years” and “A lot or two bought now will double in value in a very short time. There is no safer investment. There is no safer investment. There is no better buy.”

All you needed was 10 per cent of purchase price (cash in hand). When the price was $200 per lot, $10 per month on one lot, and $5 per month on each additional one. When the price of the lot was under $200, $5 per month would carry it.

Manchester Park was touted as the “most favourably located subdivision in Welland today-adjacent to the great Empire Cotton Mills, Bemis Bay Company, Canada Forge Company, Chipman Holten Knitting Mills, Supreme heating Co., Goodwillie and Sons Canning Factory, Lambert’s Planing Mills, Duck Fabric Company and Welland Machine and Foundry.”

A detailed street map was included with a “Key to Industries.” A guide to the “points of Interest in Welland’ directed the reader to 23 highlights, from the Water Works Pumphouse to the public school to the Laughlin Realty Company Ltd. Office, the turning basin of the Welland Canal and the Temple Club.

Although the article is a blatant {and probably expensive, for its time} advertisement of the company, the information and photographs present an emerging community of 9,000 with 25 operating industries and a Dominion government-financed canal with a $50,000,000 price tag and “work…now under way.” With seven railroads, Welland was absolutely the best town for shipping conveniences in Canada.”

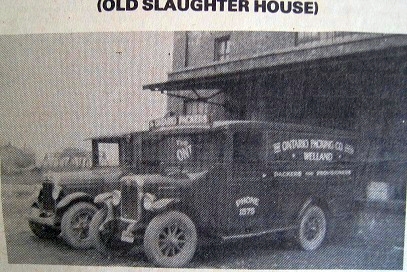

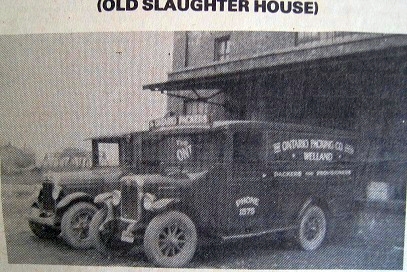

(OLD SLAUGHTER HOUSE)

By David l. Blazetich, from the files of his grandfather George “Udy” Blazetich

[Date Unknown]

A long time ago, the residents of 7th Street, in Crowland, were often disturbed by the unpleasant sounds and smells emanating from the Ontario Packing Plant, affectionately referred to as “The Old Slaughter House”. One consolation, however, was that the neighborhood could purchase fresh meat at cost price on the slaughter house premises.

The Ontario Packing Plant was opened on August 19th, 1922 with Frank Ahman as its president. Among the first employees, brought in from Kitchener, were many Senior A hockey players including well-known Art Barlett of the Kitchener-Waterloo Dutchmen.

The Old Slaughter House later became the home of Stan Reid’s used automobile dealership and, still later, Sunnyside Dairy, which is still owned and operated by Al lan Pietz, M.L.A.

lan Pietz, M.L.A.

In the accompanying photographs, note in the background the swing bridge (Black Bridge) at the foot of Sixth Street, and the McCabe House, the subject of a previous article by this writer.

*Note also the present owner of Sunnyside Dairy as depicted in 1954 with his father, Deputy Reeve Paul Pietz of Humberstone Township, Warden in 1952. At that time, his son, Deputy Reeve Allan Pietz at 24, was the youngest man ever to serve on Welland County Council. They were the first father and son combination in the history of Welland County Council.

Honoring Harry Diffin’s Unrivalled Record of 31 years and 6 months on City Council

By Mark J. LaRose

[Welland Tribune, 17 February 1987]

On February 21, 1987, we will be celebrating and honoring a community leader without equal in the city of Welland.

For devotion to the community and unselfish service to his fellow man, Harry Diffin has to be the “Man of the Half Century” in the city of Welland. No citizen has worked so tirelessly for his city without concern for personal gain or aggrandisement.

Harry Diffin’s character and reputation has been flawless, yet he has the common touch. It’s appreciatively acknowledged that he gave of his life to the fullest in the service of this community.

Seemingly almost continuously, over the past 42 years he has served as mayor and alderman until his recent retirement from public office (1985) with an unparalleled actual service record of 31 years and six months on city council.

For the past 18 years he has served as chairman of the Welland Development Commission. He is a long-standing active member of the Optimist Club and the Welland Jaycees.

Throughout all this, he has been the devoted father and husband, the good friend and gracious host. He is a man who is honest and will call things as he sees them. We salute Harry Diffin as “Man of the Half Century in the city of Welland.

A business trip to Toronto and back could take as long as five days

By Robert J. Foley

[Welland Tribune, 7 April 1992]

Getting from one place to another in the Niagara Peninsula is fairly simple for us today. A 30-minute ride from Welland puts us just about anywhere we would wish to go. We can leave home at 9 a.m., drive to Queenston, transact our business and be home for lunch. Even business in Toronto can be wrapped up and we can be home for dinner.

Travel in the 1820s was not as easy. Road conditions were subject to the whims of Mother Nature. Two days of driving rain turned hard-packed roads into quagmires of impassible mud. A trip to York (Toronto) was a major undertaking.

The sun had not yet made its appearance when young Abraham Stoner said good-bye to his father, Christian. Abraham was going to York on family business and he was meeting a friend at Cook’s Mills who was going to Chippawa with his boat for supplies. The first leg of his journey was to catch the four o’clock stage to Queenston. The stage ran on Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Fortunately, the weather was good and the Portage Road would be reasonably good for travelling.

Abraham had never been to Chippawa and after the isolation of the farm he was awed by the hustle and bustle at this southern terminus of the Portage Road. Schooners and barge-like, flat-bottomed boats were transferring goods to and from wagons that seemed to be strewn haphazardly along the docks or lined up along the road.

He searched out the stage office and purchased his ticket on the Chippawa-Newark coach. The clerk informed him that he was the fourth passenger so the coach would leave as scheduled. If four passengers did not buy tickets by four o’clock the stage was held over until seven the next morning.

The coach rolled out of Chippawa on time and even though the stage seemed to find every pot hole, rattling Abraham’s teeth, he felt growing sense of excitement. They passed rumbling wagons and carried goods around the Falls of Niagara for shipment on to York, Kingston and Montreal. An occasional caliche, a two-wheeled gig that seated two people, would flash by at incredible speeds, or so it seemed to Abraham.

The stage arrived after dark and he found himself a room at the inn and attempted to get some sleep.

The next morning, the sight that greeted his eyes left him speechless. If Abraham was in awe of Chppawa he was flabbergasted by Queenston. He counted 60 wagons lined up at the docks to unload merchandise onto the ships moored there.

Having found the “Annie Jane”, the vessel that was to take him to York, and ascertaining her sailing time, he headed off to get some breakfast. The crossing would take eight or nine hours depending on the wind and he wasn’t sure if he could eat aboard. Friends teased him about sea sickness and he hoped that it was only teasing.

The crossing was fairly smooth and Abraham found that as long as he stayed on deck his stomach remained relatively calm.

After docking he went off to find accommodations for a least two nights and prepared to go to the government buildings the next day to settle his family’s business.

Abraham Stoner finished his business and spent one more night in York’s boarding schooner for the return trip. By the time he reached home he has been gone for five days. There is a good chance that he walked most of the way from Chippawa to Humberstone unless he was lucky enough to hitch a ride with a farmer on the Chippawa Creek Road.

Freight moved through the peninsula to and from the Northwest. Many fur traders moved along the Portage Road between Queenston and Chippawa patronizing the taverns that dotted the landscape. The trip from Queentson was slow and tedious. Although two oxen could easily pull a ton of cargo from the top of the escarpment to Chippawa, it took four or five to pull the load up from the Queenston docks to level ground. The wagons used on the road were supplied by local farmers who supplemented their income by hauling freight.

Growth along the Portage Road in Stamford Township became inevitable. The intersection of Lundy’s lane and Portage Road saw a fledgling community emerge right after the war that eventually became Drummondville. Stamford Village was laid out near the Stamford Green and St. John’s Church.

Freight destined for points in the interior was moved most often by water. The Chippawa was a busy waterway that was navigable up past *Browns Bridge. Lyon’s Creek was also of major importance. The creeks along the Niagara such as *Street’s, Frenchmen’s and Black all had small ribbons of settlement along their banks and were used extensively to move the goods of the farmers to their homesteads.

William Hamilton Merritt was beginning to flex his muscles again about this time and the Welland Canal was to change the transportation system in the peninsula and in Canada forever.

*Brown’s Bridge was s small settlement built around the bridge that once crossed the Chippawa at the foot of Pelham Road in Welland.

*Street’s creek is now known as Usshers creek. Its name was changed to honor Edgeworth Ussher, a militia officer, murdered during the rebellion of 1837-38.

A business trip to Toronto and back could take as long as five days

By Robert J. Foley

[Welland Tribune, 7 April 1992]

Getting from one place to another in the Niagara Peninsula is fairly simple for us today. A 30-minute ride from Welland puts us just about anywhere we would wish to go. We can leave home at 9 a.m., drive to Queenston, transact our business and be home for lunch. Even business in Toronto can be wrapped up and we can be home for dinner.

Travel in the 1820s was not as easy. Road conditions were subject to the whims of Mother Nature. Two days of driving rain turned hard-packed roads into quagmires of impassible mud. A trip to York (Toronto) was a major undertaking.

The sun had not yet made its appearance when young Abraham Stoner said good-bye to his father, Christian. Abraham was going to York on family business and he was meeting a friend at Cook’s Mills who was going to Chippawa with his boat for supplies. The first leg of his journey was to catch the four o’clock stage to Queenston. The stage ran on Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Fortunately, the weather was good and the Portage Road would be reasonably good for travelling.

Abraham had never been to Chippawa and after the isolation of the farm he was awed by the hustle and bustle at this southern terminus of the Portage Road. Schooners and barge-like, flat-bottomed boats were transferring goods to and from wagons that seemed to be strewn haphazardly along the docks or lined up along the road.

He searched out the stage office and purchased his ticket on the Chippawa-Newark coach. The clerk informed him that he was the fourth passenger so the coach would leave as scheduled. If four passengers did not buy tickets by four o’clock the stage was held over until seven the next morning.

The coach rolled out of Chippawa on time and even though the stage seemed to find every pot hole, rattling Abraham’s teeth, he felt growing sense of excitement. They passed rumbling wagons and carried goods around the Falls of Niagara for shipment on to York, Kingston and Montreal. An occasional caliche, a two-wheeled gig that seated two people, would flash by at incredible speeds, or so it seemed to Abraham.

The stage arrived after dark and he found himself a room at the inn and attempted to get some sleep.

The next morning, the sight that greeted his eyes left him speechless. If Abraham was in awe of Chppawa he was flabbergasted by Queenston. He counted 60 wagons lined up at the docks to unload merchandise onto the ships moored there.

Having found the “Annie Jane”, the vessel that was to take him to York, and ascertaining her sailing time, he headed off to get some breakfast. The crossing would take eight or nine hours depending on the wind and he wasn’t sure if he could eat aboard. Friends teased him about sea sickness and he hoped that it was only teasing.

The crossing was fairly smooth and Abraham found that as long as he stayed on deck his stomach remained relatively calm.

After docking he went off to find accommodations for a least two nights and prepared to go to the government buildings the next day to settle his family’s business.

Abraham Stoner finished his business and spent one more night in York’s boarding schooner for the return trip. By the time he reached home he has been gone for five days. There is a good chance that he walked most of the way from Chippawa to Humberstone unless he was lucky enough to hitch a ride with a farmer on the Chippawa Creek Road.

Freight moved through the peninsula to and from the Northwest. Many fur traders moved along the Portage Road between Queenston and Chippawa patronizing the taverns that dotted the landscape. The trip from Queentson was slow and tedious. Although two oxen could easily pull a ton of cargo from the top of the escarpment to Chippawa, it took four or five to pull the load up from the Queenston docks to level ground. The wagons used on the road were supplied by local farmers who supplemented their income by hauling freight.

Growth along the Portage Road in Stamford Township became inevitable. The intersection of Lundy’s lane and Portage Road saw a fledgling community emerge right after the war that eventually became Drummondville. Stamford Village was laid out near the Stamford Green and St. John’s Church.

Freight destined for points in the interior was moved most often by water. The Chippawa was a busy waterway that was navigable up past *Browns Bridge. Lyon’s Creek was also of major importance. The creeks along the Niagara such as *Street’s, Frenchmen’s and Black all had small ribbons of settlement along their banks and were used extensively to move the goods of the farmers to their homesteads.

William Hamilton Merritt was beginning to flex his muscles again about this time and the Welland Canal was to change the transportation system in the peninsula and in Canada forever.

*Brown’s Bridge was s small settlement built around the bridge that once crossed the Chippawa at the foot of Pelham Road in Welland.

*Street’s creek is now known as Usshers creek. Its name was changed to honor Edgeworth Ussher, a militia officer, murdered during the rebellion of 1837-38.

By Robert J. Foley

[Welland Tribune, 29 February 1992]

As the crops ripened in the fields in the fall of 1820 and harvest time drew near preparations began for the coming winter. Chores essential for the survival of the family in the harsh days to come filled their days. Some of the older children inspected the mud and moss mortar that sealed up the cracks in the log wall of the house. Any weaknesses that the cold winds of winter might explore were repaired.

There were winter clothes to make as well as preserves of wild berries and garden vegetables to be put up. At this time of the year the women headed for the nearest marsh to pick the elderberries and blueberries that were abundant there. In the Welland area the Wainfleet Marsh was a popular spot for berry picking.

The butchering bee was a social occasion as well as a working day. Several neighbors gathered in turn at each other’s farms to slaughter and dress the meat for the smoke house. Beef was by far the favourite, however, more often than not it was hogs that provided the larder with most of its stock.

Before the killing of the hogs began a large kettle was set in the yard and a fire built under it. Usually one of the older boys was given the task of keeping the fire going to insure that the water was kept boiling. After being killed the carcass was scalded in the kettle to facilitate skinning. The fat was then gathered, cleaned, melted down and set in containers to cool. This became lard and would show up in the cakes and pie crusts that winter.

Smoking was the way that meat was preserved. Shoulders and sides of beef and pork were hung in the small building usually situated near the house. Sticks of birch, hickory or maple smouldered filling the place with smoke thus curing the meat. Sometimes corn cobs were used instead of wood. After being smoked the meat was covered with cotton cloth and given a coat of whitewash to discourage spoilage. The smoke house often doubled as a storage area for the cured meat.

Cuts of meat unsuitable for smoking were ground up and made into sausages. Preparing the intestines of the slaughtered pigs the women spent the day talking and stuffing the gut with pork and beef flavoured with salt and any other herbs that could be obtained either from the surrounding land or purchased in town. The head and feet were soaked and scraped, then boiled, the former to make head cheese, the latter souse. As you can see little of the animal was wasted by the early pioneers.

After completing the butchering the tallow from the slaughter was used to make candles and soap. This shortage of hard currency made the purchase of these two commodities out of the reach of most farmers. However, they often had to buy extra tallow to ensure a supply of candles to last the season.

Candle making was quite an art in itself. The large kettle in the yard that was used in the butchering was half filled with water that was kept hot with a small fire. The tallow was placed in the kettle and allowed to melt. Six cotton wicks, each ten to twelve inches long were tied to sticks two feet long. Holding two sticks in her right hand the woman of the house began dipping the wicks through the floating tallow allowing them to pick up a little with each pass until they reached the desired thickness. The sticks were then hung between two forked sticks to allow the candles to harden and the process began all over again.

It took expertise to make a smooth candle that burned evenly. There was nothing worse than trying to read or sew by the light of a sputtering, smoking candle. A good candle maker got a yield of a dozen candles to the pound and could process ten pounds of tallow at a sitting.

One of the sources of ready cash to the farmers of the peninsula was potash. This product was in ready demand and led to the deforestation of much of the province. Potash was made by cutting down trees and allowing the leaves and twigs to dry. They were then stacked and burned until the whole was reduced to ashes. Carefully raking the ashes off the top of the pile, the farmer poured them into a container called a “leach”, with lime and water. The lye produced by this mixture was drained through the bottom of the “leach” into an iron pot. The lye was then boiled until it thickened and was poured into a kettle-shaped half cooler. The final product was a very hard, brown material that was packed two to a standard oak barrel. Each barrel weighed about seven hundred pounds and would fetch the farmer $40.

The hard working people of the peninsula had little time for relaxation and fun. Much of the time they would combine leisure activities with the necessities of survival. An hour or two of fishing rested the farmer and added variety to the family diet. A morning beside a known deer trail was both relaxing and added to the larder for the winter.

After the chores were done the family gathered and played checkers while mother sat in her rocking chair and sewed. Books were scarce especially after the war, however, reading was popular and whenever the opportunity arose it was worth the expenditure of a candle. Books were often passed from one family to the other in the district. The first library in the peninsula was set up in 1824 at Brown’s Bridge located at the foot of Pelham Road in present day Welland.

With all this activity the farmer kept one eye on the weather and the other on his crop. The harvest was the most critical time for him and his family. Their survival depended on it.

Part 1

By Lara Blazetich, from the files of her grandfather George “Udy” Blazetich

*Information courtesy of Marguerite Shefter Diffin

[Welland Tribune, 1991]

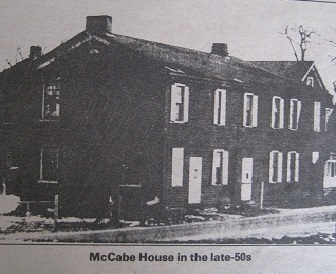

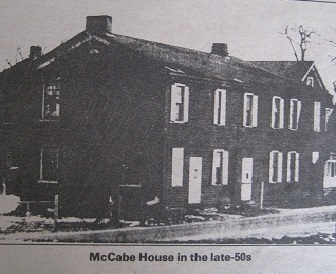

Shown to the right is the McCabe Hotel in the late 1850s, just before it was demolished. The original structure was built in Crowland in 1850 by James Tufts, Miss Addie McCabe’s great –grandfather.

Shown to the right is the McCabe Hotel in the late 1850s, just before it was demolished. The original structure was built in Crowland in 1850 by James Tufts, Miss Addie McCabe’s great –grandfather.

The hotel was operated by Tufts and his wife, Charlotte (Brailey) for many years. Three generations have been born within its walls. The hotel was located at 25 Canal Bank in Crowland Township, just south of the railway tracks adjacent to the railway bridge spanning the canal.

When the hotel was built it had a six-post veranda, upper and lower, across the front on which was draped a large sign lettered “The Travellers Home.” On one end of the sign was printed a picture of a stage coach and horses, and on the other end a picture of the Tow Horses. These horses were used to pull the barges in the canal. A large ballroom on the second floor was a popular haven for residents who attended dances and other functions held in the hotel.

Tufts owned 1,000 acres of land, 500 acres of forest, and 500 acres of marshland. He employed 10 escaped slaves from the South as woodcutters, selling the wood to passing boats and trains.

One of the slaves was Jim Wilson, who was later married in the McCabe home. Many hunters stayed at the hotel during the hunting season and hunted in the nearby marshland. James Tufts came from Mallorytown near Brockville. He descended from Peter Tufts, who was born in England in 1616 and came to America and lived in Charlestown prior to 1638. He married Charlotte, daughter of Elia and Leah (Morris) Brailey, who moved to America about 1686 from York, England.

The Brailey original homestead was located at Doans Ridge in Crowland, and they operated a hotel that was situated just west of Diffins Coal Dock (now a seniors centre).

The demolished hotel was actually on the canal waterway, before the canal was widened.

The Tufts family name was, and still is prominent in the history of Crowland. James Tufts married Charlotte Brailey. And son Wallace married Maria Hanna. Wallace and Maria had eight children: Emerson, George, Beatrice, Addie, Rena, Elva, Stanley and Curtis.

J.C. Diffin, mayor of Welland in 1921, married Elva Tufts and she was the mother of Harry Diffin, who was also the mayor of Welland from 1948-50. Diffin was also selected as Man of the Half Century in 1987.

He served 31 years and six months on Welland city council.

Sarah Tufts, daughter of James, married J. McCabe, and their daughter Addie, who never married, operated the McCabe House for many years.

DOWN MEMORY LANE – CROWLANDS’S MISS ADDIE McCABE (1954)

Part II

By Lara Blazetich, from the files of her grandfather George “Udy” Blazetich

*Information courtesy of Marguerite Shefter Diffin

[Welland Tribune, 7 February 1991]

The following is an exclusive interview conducted by Norman Panzica, former Tribune staff reporter, with Crowland’s remarkable citizen, Miss Addie McCabe.

The tiny old lady sat perfectly still as Addie put the finishing touches on her regular chore of hair combing. In the next room several men sat smoking, some of them not moving or speaking.

Just off the room where they sat, a blind man enjoyed the music from a radio from his room.

In the living room, a cerebral palsy victim sat as though in silent conversation with an old gentleman across from him. Upstairs in a bedroom, a man who had been on crutches for nine years waited patiently for the time Miss McCabe would bring a full dinner tray to him.

The guests, 25 in all, and all pensioners reside in McCabe House, a building more than a century old at 25 Canal Bank Rd., just south of the subway under the New York Central Railway.

For the lodging and care, they pay what works up to $8.30 a week. Each gives Miss McCabe his or her monthly $40 pension cheque and $4 is returned.

McCabe House is a huge structure containing many remnants of an era when gentlemen drank sherry, from dew drop-shaped decanters, and canal horses were stabled between periods of pulling boats along the canal.

“Travellers Home,” as it was known, boasted specially-made walnut furniture, and its patrons rested their elbows on a solid walnut plank more than 10 feet long and four inches thick. The cupboards, which held liquors on display, are now carry-alls. The shirts and underclothing of pensioners hang from the lines in the ballroom where gala dances were held before the day of the phonograph.

Where fashionable hunters once tossed reins to a stable boy, a 1954 transient asks for and gets a night’s lodgings and a substantial meal. At least four radios, a piano, and an organ entertain the residents. In one of the sitting rooms a Bible rests open on a stand.

From this point, prayer meetings are held each Thursday evening for those interested.

In nearly all of the 22 rooms, clean cots and beds of various sizes are to be found. Everywhere cleanliness is pronounced.

Miss McCabe, who does all the cooking, employed two house-keepers. Evening snacks among the “guests” were quite common.

Miss McCabe during the early 1930s, was employed as a cook at the Station Hotel operated by the Fred Kilgour family. This was confirmed by Katie Kisur Martin, who also worked at the hotel. Miss McCabe is a truly remarkable woman and surely deserving of the warn gratitude of the community for a noble aim in life-that of doing good unto others.

A labor of love and with devotion-at the old McCabe House.

Miss McCabe’s two sisters, Jessie Niger, from New York City and Charlotte Twomey, were regular visitors at the McCabe House. A relative, Kevin Twomey, resides in Fenwick.

Miss McCabe was born in 1879 and died in 1963 at the age of 84.

Subscribe..

Subscribe..

Eric Waterfield was born in Woodstock. He graduated from the Pharmacy program at the University of Toronto in 1941. He trained as an officer for the Canadian army and was stationed in England, but never saw active duty.

Eric Waterfield was born in Woodstock. He graduated from the Pharmacy program at the University of Toronto in 1941. He trained as an officer for the Canadian army and was stationed in England, but never saw active duty.

lan Pietz, M.L.A.

lan Pietz, M.L.A. Shown to the right is the McCabe Hotel in the late 1850s, just before it was demolished. The original structure was built in Crowland in 1850 by James Tufts, Miss Addie McCabe’s great –grandfather.

Shown to the right is the McCabe Hotel in the late 1850s, just before it was demolished. The original structure was built in Crowland in 1850 by James Tufts, Miss Addie McCabe’s great –grandfather.